It isn’t every day that an Aboriginal girl is talent-scouted while using an ATM in Darwin.

The story of Maminydjama “Magnolia” Maymuru’s selection as the Northern Territory representative for the Miss World national finals certainly adds to the pile of rags-to-riches narratives, such as the waitresss to Hollywood starlet story.

Maymura’s selection overcomes deeply entrenched definitions of beauty as exclusively European, from the beau ideal of the ancient Greeks (as defined by an aqualine nose) to the “Negro-ape metaphor”, which cast peoples of dark skins with “savage”, “ignoble” visages.

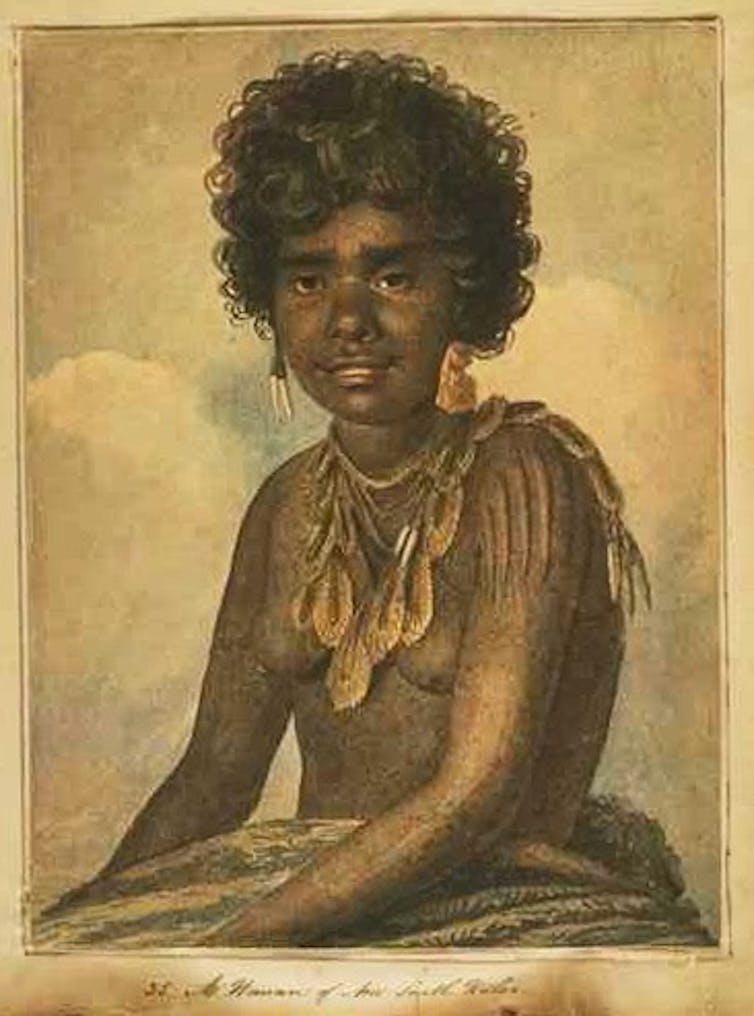

During the exploratory and colonising eras, Aboriginal women’s appearance was derided as “hideous” and “haglike”. It was wrongly thought to bear the scars of their “brutal overlords” and women were said to age prematurely due to exposure to the elements and the attendant hardships of “primitive” life.

Settlers’ appraisal of the physicality of Aboriginal women served their interests. These “attenuated” beings were fated to die out, rather conveniently. Clearly diseased and impoverished women became representative of the destiny of their race, instead of eliciting the urgent care and provision they were demonstrably in need of.

But young Aboriginal women attracted the solicitations of newcomer men, most of whom had came to their shores with a store of misconceptions about the libidinous and sexually accommodating “Native Belle”. Young Aboriginal women’s beauty has always been celebrated, such as the 1801 description by French scientists of Tasmanian belle Ouré Ouré’s “delicate” form, hospitable gestures and “tender expressions”.

Similarly William Henry Suttor, a member of parliament, recalls in 1877 meeting Maria, alias “The Soldier” or Jacky’s mother, when she rescued a young man from his upset canoe:

She had her masculine nickname from her majestic walk, and tall upright figure. A Roman empress, full of pride of royal beauty and of imperial power, could not have moved with a more graceful and dignified freedom. She dropped her opossum’s fur cloak – her garment – from her shoulders, and posing on the bank for a moment, a splendid, nude, and breathing bronze.

Maria was later found half-starved trying to breastfeed her dying sister. Beauty has never been a protection again the violence of systemic racism.

As the urban centres of Europe industrialised, a certain longing, even nostalgia, for living in a “state of nature” intensified and focused on the “Native” within primitivist discourse. Evidently, it has cast a long shadow.

Maymuru’s beauty is being celebrated for its “natural” – even “traditional” – qualities, framed within her origins in the remote community of Yirrkala. Her hunting and fishing skills are much lauded.

This appraisal revives the spectre of the “Native Belle”, the feminine bookend to the “Noble Savage” living in a state of paradisiacal nature.

As a contemporary model, Maymuru is being respectfully portrayed by media commentators. There is no hint of the hypersexualisation so endemic to early visions of the “Native Belle”, but there is plenty of the racialised romanticism that imbues the exotic.

She herself is hoping to overcome the denigration of Aboriginal youth as underachieving and worse. She’s quoted as saying,

So many people out in community have achieved so much and it’s never in the news.

Maymuru is canny about the critical role of media presence and public visibility in breaking down stereotypes and racism. She hopes to

break the cycle of how people see life back in community.

And she expresses her determination when she adds:

I want people to know that it took a lot for me to come out of my shell and do this.

Her selection to compete has prompted Arrente writer Celeste Liddle to declare herself “still anti-pageant”, arguing they’re “sexist rubbish”. But she wishes Maymuru a “brilliant experience”.

Still, Liddle rails against this emphasis on Maymuru’s “natural” beauty. And it does point to different standards, which derive from the racialisation of beauty through colonialism, slavery and concubinage.

As a celebrated beauty, Maymuru follows in the footsteps of the less well-known Indigenous woman Dolly Mundine who contested the Grafton Jacaranda Queen contest in 1969.

In Jennifer Jones’ recent retelling of Mundine’s story it seems Mundine’s accomplishments as an assimilated Aboriginal woman were particularly applauded, such as her “charm” and “poise”.

But Mundine’s story has a tragic ending. As Jones relates, her selection to compete in the Grafton Jacaranda pageant did not shield her from discrimination – while being treated for early onset leukaemia her children were forcibly removed. Mundine died at only 28 and “her children have only recently been reunited with their Mundine kin”.

Maymaru is smashing stereotyped notions of blonde, blue-eyed beauty. Still, the question remains whether Aboriginal women like her can assert a distinct Aboriginal beauty without falling into entrenched notions of the “Native Belle”, with all its trappings of exoticism and objectification.

And finally, are Aboriginal women and girls given enough public arenas for achievement and public presence outside sport and beauty – themselves hardly egalitarian gateways into wider recognition?

One only has to look at the abuse directed at Nova Peris, Australia’s first Indigenous female senator, on the news of her departure from politics, to see the racism that prominent Aboriginal woman still face in public life today.

We need to enable cultural visibility that celebrates not only the diversity of Aboriginal women’s beauty but also the diversity of their achievements.

Liz Conor’s latest book Skin Deep: Settler Impressions of Aboriginal Women (University of Western Australia Press) will be launched on 22nd June by Julian Burnside at Readings Carlton, 8.30pm.