This article is the first in a five-part series on the battle for conservative hearts and minds in Australian politics.

In July 2017 Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull upset conservatives within his own ranks by emphasising the liberal, as opposed to conservative, traditions of the party he leads.

One of the great truisms of contemporary Australian politics is that liberals and conservatives on the non-Labor side are locked in a dance in which each partner tries to dominate the other, even as they cling to each other in an endless embrace.

Many assume it has always been thus. In reality, the contemporary emphasis on the ideals of liberalism and conservatism is a relatively recent phenomenon, which political figures of the past would find somewhat puzzling.

Deakinite liberalism

In the 19th-century Australian colonies, liberalism reigned supreme. Most political figures identified as liberals and conservatives were uncommon. Even those who held conservative views, such as New South Wales politician James Martin, were happy to pose as liberals. Liberalism was not particularly ideological and often meant little more than good government.

As Australian politics divided along Labor versus non-Labor lines in the early 20th century, the non-Labor side took the name Liberal Party. Its members embraced a range of political positions, from Deakinite progressives (after Alfred Deakin) to adherents of laissez-faire economics.

As Judith Brett has argued, the key difference between Labor and non-Labor did not necessarily lie in policy as much as in the way the Labor Party pledge enforced caucus control of individual conscience. This was anathema to liberals.

Liberals in the Deakinite tradition were not opposed to state action and supported increased social co-operation, as long as that co-operation was voluntary and enhanced the individual as an ethical being. Such views can be found in the writings of the philosopher and social commentator Frederic Eggleston.

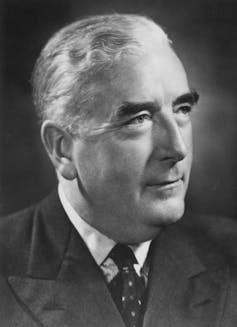

Menzies’ pragmatism

So, when Robert Menzies relaunched the Liberal Party in 1944, his motivation was not an ideological zeal to impose what today is understood as liberalism on the country. This can be seen quite clearly in his 1942 radio talks, collected as the Forgotten People.

In these talks, Menzies generally discusses freedom rather than liberty. His main focus is the individual and the family as the foundation of society, and the need for individuals to be self-reliant and to strive to improve both themselves and their families.

The Forgotten People expressed a set of moral ideals rather than a political ideology. The focus was a particular form of moral personality, not an abstract model of society. In his emphasis on the family, Menzies was not appealing to a “conservative” ideology; the importance of the family was taken for granted by all sides of politics at that time.

Menzies’ liberalism was concrete and practical in nature. It was inspired by the same philosophy, idealism, that had influenced Deakin and Eggleston. Menzies understood, for example, that in an increasingly technological society, moral ideals were needed to prevent such technology from being used for evil purposes. That is why he was a strong supporter of universities and liberal education.

As prime minister from 1949 to 1966, Menzies dominated the philosophical direction of the Liberal Party. Menzies understood liberalism in practical – and 19th-century – terms as being equivalent to good government. He did not intend to reshape society in line with a liberal ideology.

Ideological fracturing

One of the most interesting developments of the 50 years since Menzies’ retirement is that the non-Labor side of politics has become more ideological. Deep fractures have emerged between those who identify as liberals and those who consider themselves to be conservatives. This has happened at a time when, in many ways, liberalism has triumphed as an ideology in Australian life.

For example, the ideal of the family, which was so strong in the Forgotten People, has taken something of a battering at the hands of almost all political parties.

The individual is now the central political ideal, and there has been an increasing focus on rights, something Menzies would have viewed as alien to the Westminster system that Australia inherited from the United Kingdom.

The 1980s were a crucial period of transformation. Malcolm Fraser, prime minister from 1975 to 1983, can be understood as the last of the old Menzies-style liberals, but many Liberals largely disowned him for not being more economically liberal during his term of office.

Fraser was followed not only by the economic reforms of the Hawke-Keating Labor governments, but the full emergence of a far more ideologically committed liberalism in the Liberal Party. The party’s more economically liberal “dries” fought and defeated the Deakinite “wets”. This culminated in the Fightback! program of John Hewson and the defeat of the Liberal Party at the 1993 election.

Howard’s ‘broad church’

The genius of John Howard was to recognise that there was only so much liberalism the Australian people would tolerate, and to reinvent the Liberal Party as a custodian of both economic liberalism and social conservatism. Howard was fond of describing the Liberal Party as a “broad church”, which was “at its best when it balances and blends those two traditions.”

However, he also made the Liberal Party more ideological, as conservatism emerged as an ideology alongside liberalism. Howard completed the process through which conservatism and liberalism emerged as distinct – and competing – ideological positions in Australian political life.

Both Deakin and Menzies would find this ideological division puzzling. For them, liberalism was less an ideology than a moral outlook on the world that encouraged individuals to act in a responsible and ethical fashion.

Howard’s broad church worked well, as long as he was at the helm. Once he was gone, the Liberal Party seemed to erupt in conflict between liberals and conservatives. More than a decade later, the conflict shows few signs of reaching a peaceful resolution.