Infectious diseases that once were tamed are roaring back, past the last line of our antibiotic defences. They threaten the lives of millions, but where is the public outcry?

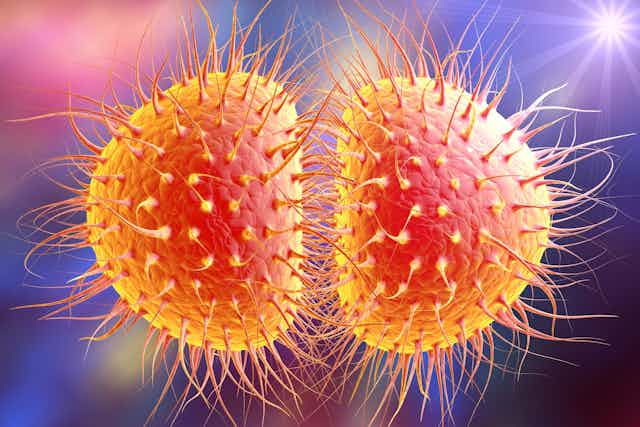

Drug-resistant strains of gonorrhoea, once easily dispatched with penicillin, are spreading across the globe. The result: chronic pain, sterility and a call for new drugs by the World Health Organization. In North America, people are dying from infections caused by bacteria that are resistant to all available drugs. And sepsis, a deadly syndrome triggered by untreatable bacterial infections, is causing millions of deaths and massive health-care costs among the elderly and very young.

Where is the Canadian co-ordination, leadership and resolve to develop new antimicrobial substances? To move innovations into the marketplace?

This spring, we represented Canada at the Drug-Resistant Infections Conference in Brisbane, Australia — an event that featured academic, public health and pharmaceutical industry researchers from around the world. The goal of the conference was to showcase the best research and development available to battle the antibiotics crisis. We are proud to report that Canadian research is among the most innovative in the world.

The time is right to launch a Canadian Anti-Infectives Innovation Network. It is time to coalesce and co-ordinate Canadian academic, private sector, not-for-profit and government research to solve the antibiotics crisis. Such a network would galvanize Canadian antibiotic research and development. It could ensure that we play a role on the international stage commensurate with our ability and promise.

The microbes are winning

The incredible scientific advances of the last century have allowed us to live longer and better lives by preventing or treating many diseases that were once fatal. Pneumonia, blood infections and tuberculosis were once common killers. Now they are generally cured with antibiotics. Cheap and abundant antibiotics have allowed us to cure illnesses, keep fragile pre-term babies alive, carry out safe surgeries and treat cancer.

Those very benefits have lulled us into ignoring a frightening problem that has been looming for decades, undermining that progress and threatening to undo those advances.

While we were enjoying the benefits of antibiotics, the microbes were fighting back. They were finding ways around the obstacles science and medicine had placed in their way. Now the microbes are starting to win. And although we have good reason to believe new weapons could beat them back again, for some reason the world is not making enough effort to preserve our fragile safety.

We are in this situation because of the ever-increasing number of bacteria that are no longer sensitive to the antibiotics we discovered decades ago. And because most pharmaceutical companies no longer see profitability in new antibiotic drugs. The business case is not strong for inventing drugs that patients will only need for a short time, compared to lifelong prescriptions to treat heart and blood-pressure conditions, for example.

But this is not a business case. This is a public health crisis.

Ordinary illnesses could kill millions

We are perilously close to plunging back into a time when illnesses we consider ordinary could kill tens of millions. For some deadly strains of bacteria, we are already in a post-antibiotic world. Clinicians are out of options. Once curable diseases are incurable. Six million people already die of sepsis every year for want of effective antibiotics, and the cost to the U.S. alone is $27 billion annually. Highly resistant superbugs are being found on our farms.

In September 2016, 193 members of the United Nations came together to announce that anti-microbial resistance (AMR) is the largest threat to medicine. This was reaffirmed this month in the final statement from the G20 meeting in Hamburg. Without urgent action to overcome AMR, the UK’s Review On Antimicrobial Resistance estimates the world could witness 10 million extra deaths every year by 2050. That is an increase of total deaths by one sixth.

Even those who survive drug-resistant infections will need twice as much time in hospital. And that is just one expense flowing from a problem that is expected to cost the global economy $100 trillion by 2050.

Canada could lead

In a context of neglect and inaction, and the misconception that antibiotic discovery is the job of the private sector, no country is ideally positioned to solve this problem alone. Canada, however, is in a position to lead if it wants to.

Canadian researchers have pioneered creative solutions: alternatives to antibiotics that block and inhibit resistance, innovative drug combinations that boost antibiotic activity and enhance host immunity to prevent infection.

Canada’s natural resources, including the Arctic and three oceans, have the potential to deliver new antimicrobial and anti-infective substances. Vaccine development for animals and humans can reduce our need for new drugs. Our innovative thinking can deliver alternatives to reduce dependency on antibiotics.

Canadian Anti-Infectives Innovation Network

Innovations alone won’t help. We must do more to get Canadian know-how into action immediately. Canada is a global leader in many areas of basic and applied research that can contribute to solving the problem. But we lack co-ordination, common objectives and resolve.

We need to develop our innovations so we can lead the world in alternatives and adjuncts to antibiotics. We need to become an essential partner in international initiatives such as CARB-X, a public-private accelerator funded by the U.K. and U.S., to move creative antibiotic discoveries into the marketplace. Ironically, two discoveries made at McMaster University are being considered by CARB-X for funding, following licensing to U.S.-based companies. Two others developed at the University of British Columbia, and originally the basis of Canadian spinoffs, are in advanced clinical trials with U.S. companies.

The opportunity to grow these discoveries here in Canada has been lost. So has the associated commercial, employment and skills benefits.

Canada is competing and leading in anti-infective innovation, but we are rapidly falling behind in our ability to capitalize on these discoveries, foster and support new research and commercialization in Canada.

We must act now to ensure that we not only do our share on the international stage to solve the antibiotic crisis, but also provide a made-in-Canada innovative approach. We can do so, with support and leadership, in the form of a Canadian Anti-Infectives Innovation Network that assembles leading researchers in universities, hospitals, government and the private sector.