Federal Education Minister Simon Birmingham announced last year in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook that funding for Commonwealth-supported places would be capped at 2017 levels.

For the first time in 35 years, federal government policy is set to erode skills and qualifications across the Australian population, particularly for young people.

There are many contextual factors behind one of the most significant policy issues facing higher education in 30 years: the discontinuation of Australia’s demand-driven funding system, where university places are uncapped.

According to the Mitchell Institute, by 2031 more than 235,000 students will miss out on a university education. The majority of which (70%) are now just starting high school.

Read more: Universities get an unsustainable policy for Christmas

A story of transformation and equity

Since the golden era of free tuition under the Whitlam government, Australia has seen vast changes in policy to one of its most vital sectors.

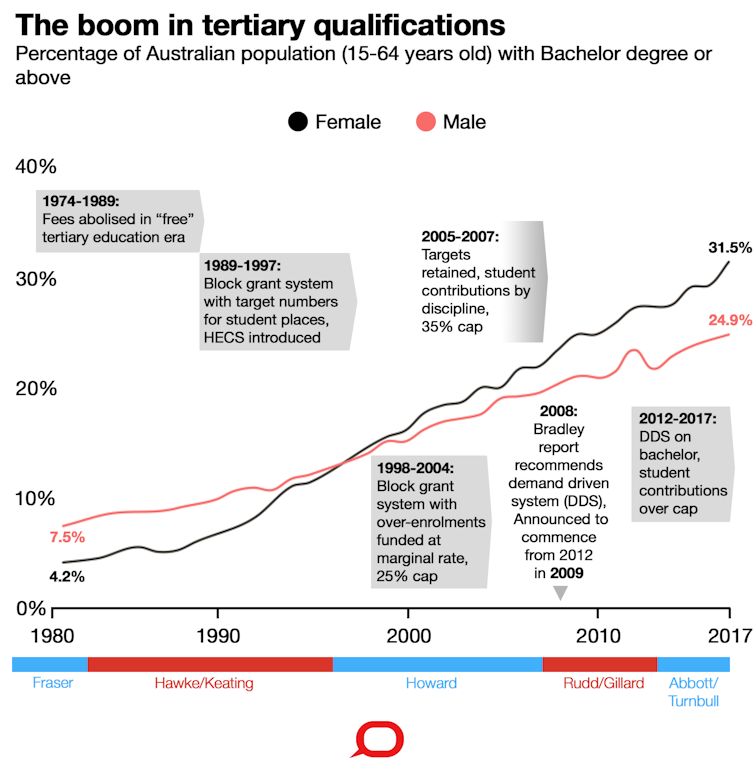

In 1970, a university degree was a rarity among workers. Only 7% of the 15-64 year old population enjoyed the privilege of a bachelor level degree, two-thirds of which (64%) were men.

Universities closed the educational gender gap in the 1980s. And in doing so, underscored a radical modernisation of the Australian workforce.

Over the last 35 years, higher education has changed our lives dramatically. Skills shortages have been addressed, industries diversified and poverty cycles broken. First in family students have beamed with new hope. Australia’s university-for-the-rich era has come to a decisive end. In its place we have seen a new equity take shape through its most transcendent means – a world class higher education that you repay when you’re able.

The end of the demand-driven system

Following the Bradley Review of higher education, the Gillard government announced the demand-driven system in March 2009 to address low participation, against global standards. Under the demand-driven system, enrolments ceased to be concentrated in a select few big universities, giving way to a great deal more diversity in enrolment across institutions and in the actual student body.

While the system enabled far greater choice and competition, the government never entirely vested its trust in the student market. Rather, sub bachelor, postgraduate and medical places were all capped, and an emergency trigger was embedded into legislation to regain control over supply, at the government’s discretion.

Since 1982, Australia’s resident population has grown steadily by 163%. Consequently, the majority of growth in higher education participation actually occurred in the 25 years prior to the introduction of the demand-driven system.

Essentially, before the demand driven system, places were capped. After its introduction, the market quickly corrected itself and the supply of places caught up to demand. The implication is that over time, it becomes increasingly difficult to reintroduce an uncapped system. If the government decided to reintroduce it down the track, we’d have the same issue of oversupply and excess demand. Especially if you have a baby boom on the way.

With all this in mind, there is really only one problem with the demand-driven system. It costs more than our society is currently willing to bear.

Wicked dilemmas before a looming election budget

It’s a wicked dilemma for the government to wrestle with in the lead-up to the federal budget. The prevailing deficit of over A$23 billion and a plenitude of wishful demands to head off 30 consecutive Newspoll losses, while a federal election looms large.

The root question is relatively simple: do we value education?

The answer is: well, it’s complicated.

Cutting funding to a sector that generates intellectual capital, skills, new knowledge and drives innovation, while redirecting efforts to a A$65 billion company tax cut is a high stakes game of chance.

The Business Council of Australia have made it clear a “university setting is not the best learning environment for all Australians”. Rather, there is a dire and urgent need to “create the conditions for higher incomes” through company tax cuts. But evidence from the US suggests corporate tax cuts are likely to increase inequality, as benefits are unevenly distributed, especially for workers.

Read more: Budget policy check: do we need company tax cuts?

A solution looking for a problem

Other than fiscal pressures, constricting the supply of education to thousands of students intends to solve a problem that has to date not been precisely defined.

Contrary to the government’s corrosive narrative, the sector has an optimistic bill of health. Graduate outcomes are good and getting better (86.5% employed overall in 2017), overall student satisfaction is high (80%), attrition is stable (15%) and Australian universities are increasingly recognised as among the best in the world. The chronic search for a common problem has us confused and divided.

Capping places per institution not only limits the number of students who can study at university, but in an increasingly specialised sector it also undermines unique competitive advantage.

The noughties baby boom

Shortly after 2020, Australia will experience a boom in the 18-25 year old population. Population growth for this group significantly differs from those in the 18-64 year old bracket, which is moderate and slowing. As funding increments are drip-fed to the sector, growth in demand among Australia’s youth will outstrip the supply of places, leading to a long-term erosion of skills and qualification.

The legacy of a cut higher education system is a less skilled future workforce, and an Australian youth that miss out on the educational opportunities afforded to their parents.

In Finland, higher education is free, to engender opportunities for all. By comparison, Australia has a larger population and landmass, but a significantly (22%) higher per capita GDP. By this measure, Australia is number nine in the world’s top ten rich list.

But, Commonwealth support for university places comes at a cost. There is a ceiling on our willingness as a society to accept paying more. We may have simply reached “peak funding” for higher education.

While few would realistically expect a return of tuition-free university in Australia, some sentiments live on. As citizens, we are all diminished when any one of us are denied the opportunity of an education.