Anzac Day continues to feature on the Australian calendar as a day for celebrating and commemorating the deeds of our military personnel.

Traditionally focused on the first world war, the mythology of the Anzacs – bronzed bushmen storming the cliffs of Gallipoli or walking fearlessly through artillery bombardments on the western front – has long clouded the reality of the experience of fighting in what was then an unprecedented conflict.

Many Australian soldiers did not fit this Anzac myth. Some were taken prisoner of war and some broke down with shellshock. Others were just “bad characters”, whose trouble-making, both within and outside their units, caused endless headaches for military and civilian authorities.

Australian soldiers stationed in Egypt, England and France were charged with various transgressions, including insubordination, repeated malingering and theft. Some were accused of committing heinous acts, such as murder and rape.

In our research on these soldiers, we found that, in total, 115 Australians were court-martialled during WWI and sentenced to death for serious military crimes – primarily desertion.

Read more: Why Australia is still grappling with the legacy of the first world war

Researching desertion

Desertion needs to be distinguished from being absent without, or overstaying, authorised leave from one’s unit. Under the military law that governed members of the Australian Imperial Force during WWI, desertion was defined as leaving or refusing to enter the front lines or being absent from areas behind the front lines for more than four weeks.

Desertion was considered such a serious offence because the soldier had refused to do the duty for which he had enlisted, wasted resources, weakened military strength and endangered comrades.

Not surprisingly, the sanction was severe. More than 3,000 members of the British empire’s forces were sentenced to death for desertion and similar offences during WWI, of whom 361 were executed by firing squad. (Among those were 25 Canadians and five New Zealanders.) The remaining deserters had their sentences commuted to something lesser – usually a substantial prison term.

But Australian law – specifically the Defence Act first passed in 1903 – effectively precluded the Australian Imperial Force from carrying out the death penalty. Soldiers could be sentenced to death, but none were executed.

In our research, we combed through amateur histories, theses and historical archives to unearth the 115 Australian soldiers who were sentenced to death in WWI (fewer than the usually cited number of 121, which we consider exaggerated). We then examined their service records, court-martial files and repatriation records.

Who were these men? We found them to be not just bad soldiers, but men for whom military service was just one unfortunate aspect of their lives.

As historians peering into their lives, we see them wrestle with their obligations in the armed forces and confront the military justice system. We witness their back-and-forth with the government repatriation authorities as they plead for financial and other assistance, and we all too often see their early or otherwise unfortunate deaths.

Two cases stick out for us: those of privates James McCormick and Nicholas Permakoff. Both had colourful service records prior to their sentences, including hospitalisation with venereal disease, insubordination and absences from their units. And both had sad and lonely, although very different, ends.

Read more: The Anzac legend has blinded Australia to its war atrocities. It's time for a reckoning

The chronic absentee

McCormick enlisted in Western Australia in June 1915 at the age of 36. He hardly saw any action on the battlefield; he spent more time in hospital suffering from venereal disease, episodes of epilepsy and stomach issues (he was identified as an alcoholic by military authorities), or in military prison.

He absconded almost as soon as he arrived in France in June 1916 and was sentenced to one year of hard labour. Reflecting the manpower issues faced by the Australian Imperial Force, his sentence was suspended in early 1917 so he could rejoin his battalion.

Two months later, McCormick again disappeared. This time, he was charged with desertion and sentenced to death. This was later commuted to ten years of penal servitude and eventually suspended again. And in May 1918 he transferred back to his battalion. He was almost immediately hospitalised for chronic stomach issues and was sent to England, where he stayed until almost the end of the war.

McCormick was finally discharged from the force as “medically unfit” in December 1918. His less-than-glorious service record made him ineligible for war medals or the war gratuity. He travelled around Australia picking up odd jobs, but continued to struggle from stomach complaints and alcoholism. He died in 1950.

McCormick’s body was found in a school shed in Albury, New South Wales, an empty wine bottle next to him and his feet in an old onion bag. The coroner attributed his death to chronic alcoholism and exposure. No next of kin was found, so the local police organised his funeral in Albury cemetery.

The deserter shot by his own side

An even more curious case – and just as sad – is that of Nicholas Permakoff. Born in Russia, he served for two years in the Russian Army before migrating to Australia where, at the time of his enlistment in 1916, he was a miner in NSW.

He later claimed he joined the Australian Imperial Force on the bizarre promise that he could transfer to the Russian Army once he was back in Europe. By the time he got there, however, the Russian Revolution was underway and Permakoff had decided he didn’t want any part of the war.

In November 1917, he told his superior officer “yes, fuck you” – or words to that effect – when ordered to put on his pack and march towards the front, earning himself a six-month prison term.

After his release, he was essentially forced to the front line, despite telling his officers he would not shoot. That night, according to Australian sentries, he was spotted without his weapon walking towards the Germans. Permakoff was fatally shot by his own side – an action later endorsed by a Court of Inquiry.

He left very sketchy next-of-kin details: “Mrs Permakoff, Archangel, c/- Imperial Russian Consul, Sydney”. Efforts to contact his mother in Archangel, a city in Russia, were unsuccessful, and the NSW public trustee could not find anyone to claim his few assets.

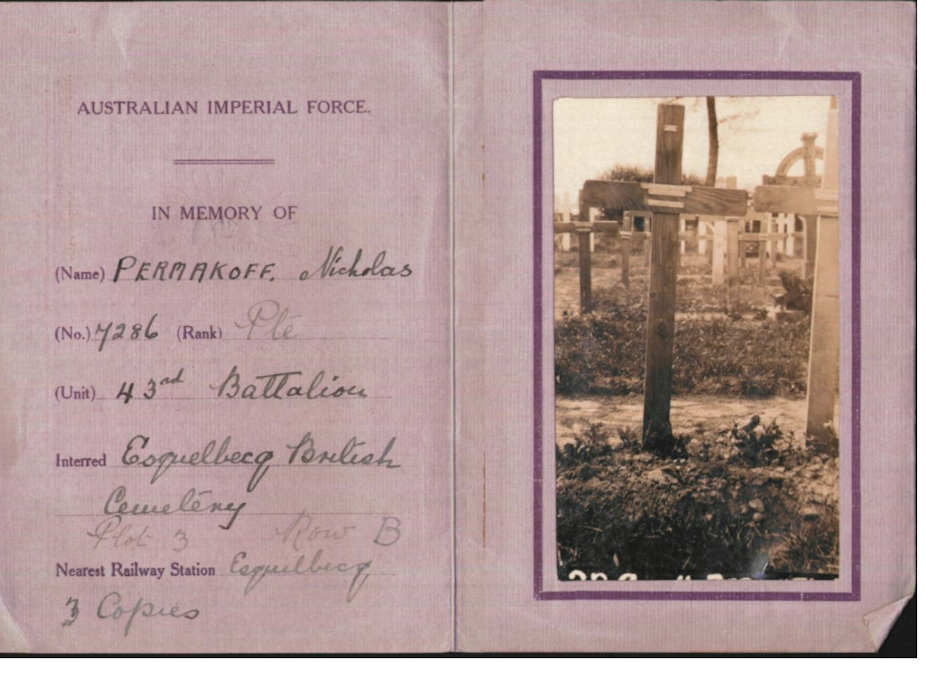

Permakoff is one of only five Australians who died in WWI to be excluded from the Australian War Memorial’s Roll of Honour. He lies in a Commonwealth War Graves cemetery in Esquelbecq, France.

Revealing the complexity of military service

There were long public campaigns in the 1990s and 2000s in Britain, New Zealand, Canada and Ireland to posthumously pardon those executed during the war.

But Australian deserters sentenced to death have remained largely overlooked. This is perhaps because they were not ultimately executed (with Permakoff’s odd exception), so they have not aroused an indignant sense of injustice.

Moreover, they present an uncomfortable counter-narrative to the idealised Anzac character and feats.

Our research seeks to rescue these men, their experiences and their voices from the historical void. Doing so enhances our understanding of the complexity and diversity of Australian military experiences and highlights the impossibility – for most – of the Anzac ideal.