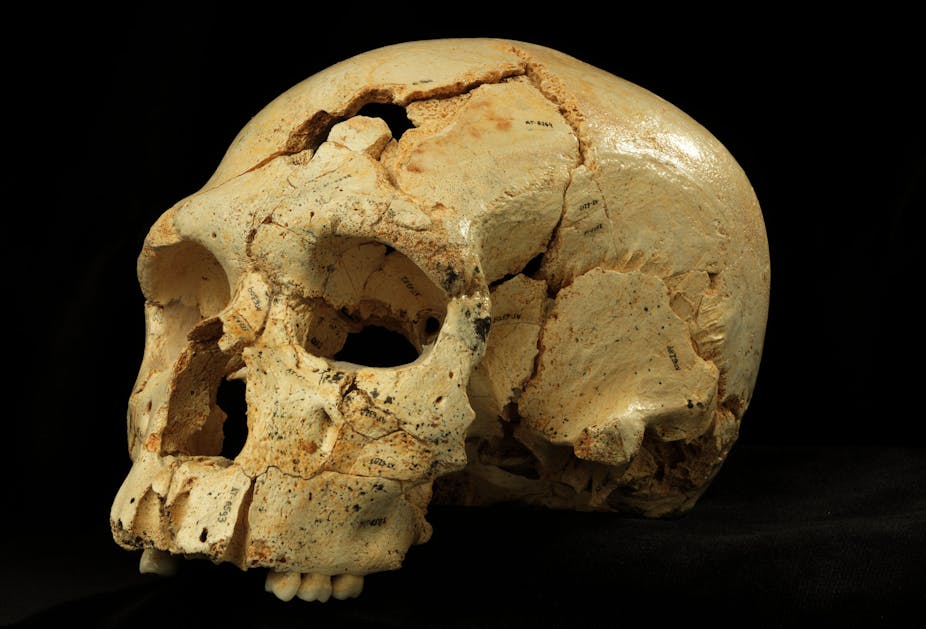

Ancient remains have confirmed that the face and jaw evolved before the rest of the skull in Neanderthals and early human ancestors.

Research conducted at the Sima de los Huesos (Pit of the Bones) archaeological site in northern Spain, and published today in Science, has confirmed a much-debated hypothesis on how our early human ancestors evolved.

The theory, known as the “accretion model”, suggests that rather than features emerging as a complete package, early human and Neanderthal evolution occurred with development in the jaw, teeth and face first. This “mosaic” evolution helped the Neanderthals survive fluctuating environments.

“The emergence of a masticatory [chewing] specialisation was perhaps a response to changing dietary requirements and resource pressure,” said Lee Arnold, ARC Future Fellow from the University of Adelaide and one of the study’s authors.

“These factors would have been heavily influenced by climate and habitat, both of which were in constant flux during alternating glacial and interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene [Era].”

The international team of researchers, led by Juan Luis Arsuaga from Centro Mixto UCM-ISCIII de Evolución y Comportamiento Humanos, painstakingly pieced together skull fragments from 17 Sima de los Huesos skulls, seven of which were previously unexamined.

Six different geochronology techniques were used to date the samples, which placed the remains at around 430,000 years old.

“This study clears up previous dating controversies associated with the site,” Dr Arnold said. “The Sima de los Huesos fossils are now the oldest reliably-dated hominins to show clear Neanderthal traits globally.”

The discovery of the first three skulls at Sima de los Huesos was published in 1993, and since then the site has provided a wealth of archeological information on our early ancestors.

This new research has also suggested the remains examined are from a different branch or “clade” than traditional Neanderthals.

“The study had two main objectives: Establishing who these ancient people were and determining when they lived in the past,” Dr Arnold said. “Our analysis of the anatomical features shows that the Sima [de los Huesos] fossils are not simply ‘classic’ or ‘early’ Neanderthals.”

Anthropologist Darren Curnoe from the University of New South Wales said the study provided more evidence for the coexistence of various early human species.

“This is exciting work because we now have a stronger case than ever for multiple [early human] species living in Europe,” Professor Curnoe said. “At least four during the period 1 million years to 40,000 years ago.”

Dr Arnold said the samples examined differ enough from existing Neanderthal remains for them to be classed as their own “taxon” (group) and that existing alternative classifications are insufficient.

“The fossils cannot simply be placed in the species known as Homo heidelbergensis since the Sima jawbones are distinct from the type specimen of this species,” Dr Arnold said.

Colin Groves, Professor of Bioanthropology from the Australian National University, said the progress was invaluable and establishing the age of the site had been a long time coming.

“The evolution of the Neanderthal people was already quite well known in the fossil record,” Professor Groves said. “This new information from the Sima de los Huesos at Atapuerca – based on many specimens, most of them not published before – documents it in detail. And at last we have a firm date for the site.”

While the Sima de los Huesos site still has lots to tell us about early human and Neanderthal evolution, Dr Arnold said there was more work needed further afield.

“The next step is to improve the dating of other similarly aged paleoanthropological sites in the region,” Dr Arnold said. “This is a critical step for evaluating evolutionary relationships between the various Middle Pleistocene hominin populations across Europe.”