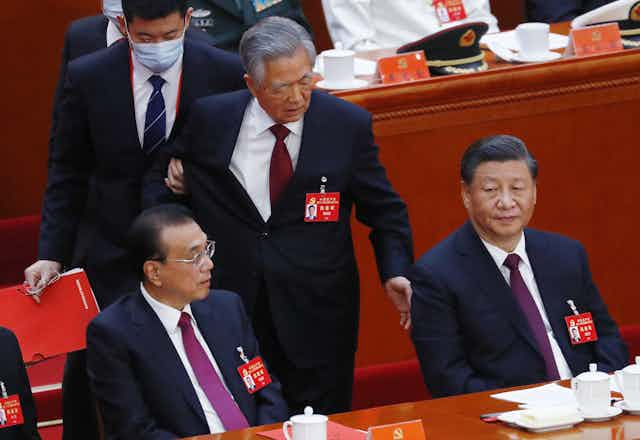

It has been suggested that the removal of Hu Jintao, Xi Jinping’s predecessor, from the closing ceremony of the 20th Communist Party congress could overshadow all other news from Beijing during the past week. Was there a health reason for this dramatic development – or was it a live purge, planned or even spontaneously decided by the Chinese president to send a clear message to everyone in the party? We may never find out.

But the photo capturing the moment of Hu being escorted out of the congress, looking desperately at an apparently cold and indifferent Xi, depicts well the end of what Hu (and Deng and Jiang before him) came to be associated with: collective leadership, internal democracy and consensus building.

During the week-long congress several changes in people, guiding ideas and policy priorities have been announced, all pointing to the same direction. Xi Jinping is now in full control of the Chinese Communist Party as his decade-long effort to centralise his power over the communist regime has been completed.

The composition of the 20th Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), the seven-member strong leading organ of the party and the country, offers the most straightforward example of Xi’s domination of China’s political system. Announced on October 23, all the positions of the PSC were given to politicians with long political and personal connections to Xi and proven loyalty.

Li Qiang (party secretary of Shanghai) and Cai Qi (party secretary of Beijing), are tenacious supporters and implementers of the unpopular zero-COVID policy. Ding Xuexiang (Xi’s chief of staff) has been close to the Chinese president since serving with him in Shanghai in 2007, and Li Xi (party secretary of Guangdong) is one of the most longstanding supporters and a family friend of the president. These four new members joined the existing loyalists from the 19th PSC, Zhao Leji (head of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection) and Wang Huning (Xi’s top theorist).

The new Politburo, the 24-member-strong pool from which the PSC is selected, also demonstrates Xi’s complete control of the party’s political elite. To achieve that, long-established rules and customs on the career progression of politicians have been only selectively applied or ignored completely, setting a precedent for future congresses. And, for the first time in decades, no women have been included in the group.

Doubling down on stability and control

On guiding ideas and policy priorities, the congress adopted Xi’s entire agenda, which was subsequently enshrined in the party’s constitution, and elected him for an unprecedented third term as general secretary. In terms of the economy, we had the reaffirmation of existing policies. No relaxation of the zero-COVID policy was announced, while the decisive interference of the state – a trend that has intensified in recent years – will continue. There was no change in reference to “common prosperity”, the idea of a more equitable growth for all, and to the emphasis on the domestic market and its capabilities for innovation as well as for self-reliance.

The underlying vision is that of China as a more inward-looking country, with a more selective engagement with the world and a universal equation of policymaking with the “core” of the party – Xi himself. For the first time since the death of Mao, there appear to be few (if any) institutional or political checks on the leader’s power.

But any comparison with Mao is somewhat simplistic. Mao thought of himself as being above the party, which he viewed as a vehicle to implement his irrational ideas and settle scores with other leaders. He surrounded himself with sycophants who knew nothing about governing a country, not loyal technocrats as Xi has. And of course, Mao did not hesitate to throw the CCP into the abyss of radicalism when he lost its control.

Read more: China: Xi Jinping poised for a third term with no plans to relinquish power any time soon

The havoc and anarchy of the Cultural Revolution that Mao created, became the context in which Xi grew up. It left deep personal wounds (his father Xi Zhongxun was abducted by Red Guards and elder sister Xi Heping committed suicide) and a distaste for disorder.

When Xi came to power in 2012, he saw laxity in party discipline and ineffective control of society as two trends that had to be tamed. A decade later, he has managed to significantly expand the party’s capacity for surveillance and repression of society, he has purged a great number of cadres who were either corrupt, potentially disloyal to him or both, and has centralised control of the communist regime.

The rise of ‘XiCP’

Xi’s version of centralisation is very different to Mao’s as it is taking place within the party. But it shares one key characteristic: collective leadership, internal democracy and consensus building are sacrificed in favour of discipline and loyalty to the “core” leader. In a setting with almost no checks on power, the personal charisma, judgment, strengths and failings of the leader have a much greater impact on the future direction and resilience of the regime than when rules and the constant need for consensus-building constrain the ruler.

In addition, history tells us that the more centralised a system is the more bitter the fight for succession is likely to be. Without a clear heir, a top leadership only united by their loyalty to Xi and reform-era succession rules and conventions gone, it will be much harder to secure a stable and orderly passing of power from Xi to the next leader. We should expect that at the first hint of Xi’s retirement or poor health, his men will draw their knives and fight for the top job.

Through centralisation, Xi has replaced the CCP with his own control-obsessed version, but at the cost of undermining the operating principles that have played an important role in the party’s longevity and success so far. It remains to be seen whether this new “XiCP” will be as successful in securing the prosperity of a dynamically changing society as the party we knew up until recently.