This year’s update on Closing the Gap presents a picture similar to 2014 in education - there is much work still to be done to improve educational outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.

Closing the gap is admirable in principle, but the practical realities are much more difficult. A complex array of factors need to be addressed, including major barriers such as geographical isolation and other physical access issues, alongside cultural and socioeconomic factors.

Closing the gap in education is intrinsically linked to multiple aspects of socioeconomic disadvantage, including access to quality health, employment, incarceration rates and housing. These combine to form the social determinants of educational success.

In education, the Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap update identified access to early childhood as “not met” and improvements in literacy and numeracy as “not on track”. School completion is “on track”, while school attendance has only baseline data from 2014.

As Prime Minister Tony Abbott himself noted, the 2015 results are “profoundly disappointing”.

Access to early childhood

The target of 95% of four-year-olds attending preschool in remote communities by 2013 was not met, with 85% enrolled.

The importance of increasing access to high-quality preschool experiences is well-documented in improving school readiness and future educational success. While the target has not been met, there is an ongoing commitment to the goal.

The National Partnership on Universal Access to Early Childhood has been extended to this year. While this is promising, much more targeted and strategic partnerships between state and federal governments, early childhood service providers, school communities and families need to be invested in.

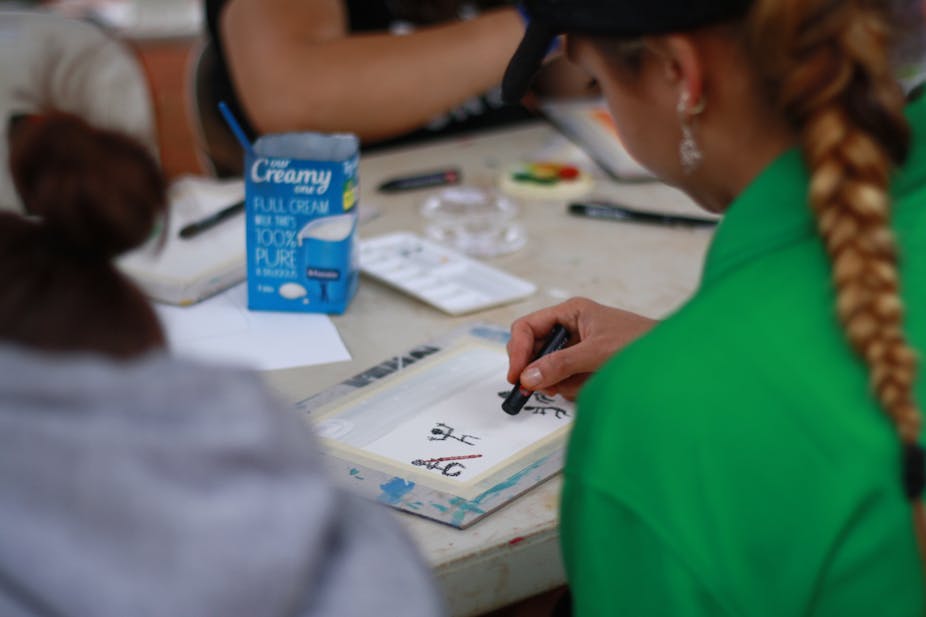

Just as important as how many students have access, is what type of access they are actually getting. There are important cultural and contextual factors that need to be considered in preparing young children for the transition to the school system, especially in remote settings where school is often first experienced as foreign and culturally challenging. Early childhood programs that are locally appropriate and supported are crucial.

Literacy and numeracy

The target to halve the gap in reading, writing and numeracy by 2018 is also not on track. This is measured according to performance on NAPLAN tests as a proportion of students meeting the national minimum standards. There are major concerns about the use of NAPLAN as an appropriate measure, particularly for Indigenous students.

In 2014, only two of eight areas were on track - Year 7 reading and Year 9 numeracy.

While 95.9% of non-Indigenous students in Year 7 were at or above the national minimum benchmark for reading in 2014 NAPLAN, the figure is only 77.1% for Indigenous students. For students living in remote communities, the figure is even more concerning, with only 34.9% reaching the benchmark.

Similarly, Indigenous performance on the Program for International Student Assessment shows a gap of about two-and-a-half years of schooling.

The government’s response to this is the roll-out of a “Direct Instruction” program to remote schools, yet the evidence base for such an approach is uncertain, as explained in this initial review of the Cape York trial and this analysis by education researcher Allan Luke.

A 2013 report by the Australian Council for Education found that:

The educational and cultural contexts in which students learn to be literate must be considered in planning for effective teaching and learning.

This is important when considering the significant impacts of socioeconomic and geographical disadvantage faced by many Indigenous children.

School attendance

Last year, Tony Abbott set a new target of 90% school attendance, claiming:

It’s hard to be literate and numerate without attending school, it’s hard to find work without a basic education, and it’s hard to live well without a job.

A report into attendance and performance on NAPLAN tests found that there were links between absences, academic performance and social disadvantage. The report also found:

There are distinct gaps in achievement depending on where students live, their socio-economic status, mobility and Aboriginal status, and these gaps were observed at all levels of attendance.

While there is evidence to suggest that improving attendance will go some way to improving educational outcomes, there are also some concerns in the research that there is a problematic assumption that attendance correlates directly to performance, without taking into consideration social context of schools and their communities, as well as the impacts of curriculum and teaching.

There are early signs of success on increasing attendance, with Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion claiming that the government’s Remote School Attendance Strategy is working.

However, experience tells us that this is a deeply entrenched issue with multiple causes. There is a great deal of policy development still to do in this area.

The focus on breaking “the cycle of truancy” should also be treated with caution if it comes at the expense of providing equitable access and resourcing for schooling, particularly in remote communities under threat of closure.

School completion

There is some good news: the proportion of Indigenous 20‑24-year-olds who achieve Year 12 or equivalent status continues to show the most promise of being fulfilled. The gap closed by a rate of 11.6% between 2008 and 2013, with 58.5% attaining Year 12 or equivalent.

However, once again geographical disadvantage comes into play, with only 36.8% of remote young people meeting the target. One measure undertaken by the federal government is providing support to private boarding schools to enrol more remote Indigenous students.

There are also calls to establish regional boarding schools with a focus on bicultural curriculum.

Federal Education Minister Christopher Pyne describes “economies of scale” to support moves to increase participation of remote students in boarding schools.

Doing better

The key to doing better lies in addressing issues of equity, access and inclusiveness in Indigenous education. Communities that are engaged and empowered, working in close partnerships between families, schools and governments, are the only sustainable way of coordinating the vast resources and willpower needed to truly close the gap.

Continued and improved investment in quality facilities and adequate resourcing of teachers and schools at a local level are needed, as well as improving school-community-work connections and connections to higher education.

While education is often touted as “the answer” to Closing the Gap, the complexities of social disadvantage in health, nutrition, housing and employment must also be addressed.

If we are to continue to engage students and families in education, the benefits and possibilities needs to be seen and delivered locally.