Isolation is regarded as one of the key pillars of the novel coronavirus containment strategy. Yet there is an important legal question about whether isolation – at home or in a hospital – is compulsory and what the consequences might be for those who refuse to comply with isolation measures.

In England, a stark answer was provided on February 10, when the government implemented a new law specifically addressing the coronavirus outbreak. This emergency legislation now allows for the lawful detention of anyone who is reasonably suspected of posing a risk of infecting others with the disease.

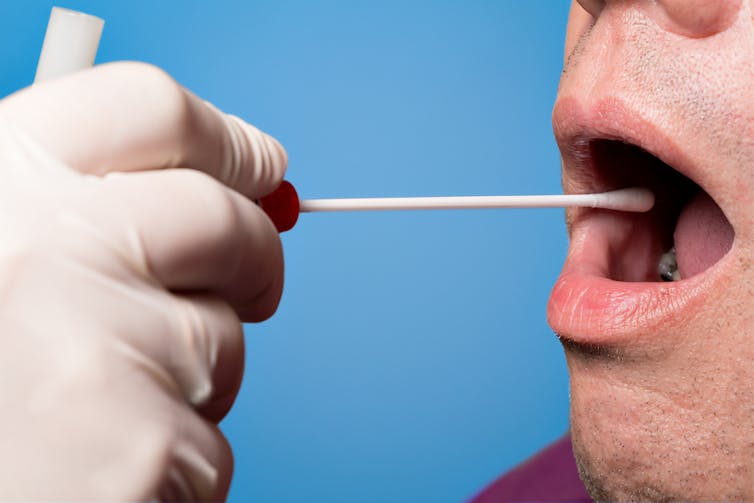

People can be detained for the purposes of screening for the virus, including the collection of personal health information and biological samples, and to isolate them from others. Detention can be authorised by the secretary of state for health or by a government health official for between 24 hours and 14 days, with the possibility of extension for follow-up monitoring.

In an unprecedented step, the law also creates new criminal offences for people who don’t comply with detention orders, abscond from a place of isolation, supply false or misleading information or who obstruct public health officials conducting their duties. The police are now empowered to use reasonable force to enforce these rules in the interests of public safety.

Draconian and invasive

It is worth noting several important points about the powers to detain and isolate. First, England is not alone in adopting these measures. Similar powers have been implemented in the US, Canada and Australia.

Second, the powers are seen as a precaution. In the first instance, people are encouraged to voluntarily comply with any public health recommendation.

Third, the powers will only be used where they are “necessary and proportional” to the risks of widespread transmission of the virus throughout the country. This means that where the risk of outbreak is officially lowered or, conversely, the virus spreads to a much higher number of people, the powers would become redundant.

But any powers that compulsorily detain people and force the sharing of health information interfere with the most basic human rights: the right to liberty and the right to privacy.

Neither of these rights are absolute, in the sense that there are recognised lawful exceptions, which include preventing the spread of infectious disease and protecting public health. But state measures that interfere with these rights must be exercised in strict accordance with the law, transparently and in a necessary and proportionate manner to achieve the aims of those laws. And those subjected to restrictions must have a right to appeal to challenge their detention.

In principle, the new laws in England respect these conditions. In practice, use of the restrictions must follow two imperatives. First, exercise of the powers must be based on the best scientific evidence available. This requires close collaboration with national and international public health experts to fully understand factors such as the incubation period of the virus, the known risks of transmissions and how to successfully manage treatment of the virus itself.

Second, the rights and wellbeing of those detained must be respected. This includes maintaining clear lines of communication, listening to those people’s concerns and always favouring the least restrictive measures required to control the risk of transmission. It also means recognising that those detained are inherently vulnerable, both in a medical sense but also to the social and emotional repercussions of being identified as a (possible) public health risk.

The government has made available powers which are, by their nature, among the most draconian and invasive measures a state can take against its citizens. It is vital that those exercising compulsory powers sensitively balance the interests of the many against the rights of the few.

What happens next in the state’s management of coronavirus is crucial, both for containing a harmful epidemic, but also for setting potentially long-lasting human rights norms in public health.