French artist Pierre Huyghe has long used animals in his work: bees, dogs and fawns frequently roam his elaborate worlds, worlds he creates in gallery and exhibition sites, transforming them into uncanny non-places, places “in-between” nature and culture.

The first solo exhibition of Huyghe’s work in Australia, currently showing at TarraWarra Museum of Art is no exception: the gallery space crawls with spiders and a colony of ants.

Huyghe’s frequent collaborator is a hound with a striking pink foreleg known as Human. Human appears in the eerie film A Way in Untilled (2012), but alas does not make a physical appearance in the TarraWarra exhibition as she did in Huyghe’s dOCUMENTA 13 installation Untilled (2013).

Nonetheless, the film captures elements of this work, in which Human, the animal, appears alongside another dog, a turtle, a beehive enclosing the head of a reclining nude statue, a multitude of insects, algae and other forms of non-human life.

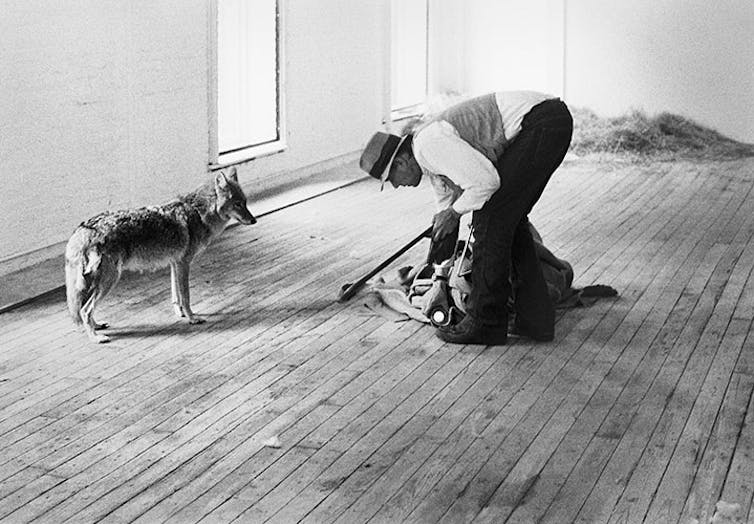

Huyghe is by no means the first artist to do this. In the late 1960s, Jannis Kounellis brought birds and horses into galleries and Joseph Beuys cohabited with a coyote in a New York Gallery in 1974. Since then goldfish, snails, asses, pigs and fleas have all played a role in contemporary art.

One might ask though: how it is that the art world has become a menagerie, at the same time as a consensus has emerged as to the questionable ethics of animals in other artistic and entertainment contexts?

Circuses with performing animals are now only to be found camped out at the margins of towns during summer holidays. The anthropomorphised circus animal, such as the tutu wearing elephants featured in 1940s “human-animal dance spectacle” Ballet of the Elephants, and described in Peta Tait’s Wild and Dangerous Performances: Animals, Emotions, Circuses (2011) is now clearly beyond the pale.

While noting that such interspecies circus performances became widely decried as exploitative, Tait also traces the complex empathic emotions that they created between humans and non-human animals, perhaps providing a clue as to the tolerance that appears to be shown for animal appearances in art.

But it is not so much empathy for animals that Huyghe seeks to create in his eco-worlds—but an uncanny sense of indifference. In an Art in America interview he described his desire that the museum visitor might bear witness to the happenstance of nature:

walking through the woods not knowing if he will find a ravine or a creek, or if an unknown animal will pass him on the left.

Huyghe’s animals are not performing but appear to be going about their everyday activities: making a hive, a nest or, in the case of the ants, just wandering about the walls of the museum. In Untilled, Human gnaws on a bone and laps up water from a puddle.

In a review of the Pierre Huyghe retrospective at the Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art in 2014, Victoria Daly suggests that the art world’s indifference to the use of animals in Huyghe’s artwork is likely based on the fact that the animals don’t appear to be suffering.

At the LACMA exhibition, Human even had her own web page. Readers were advised that she had been a rescue dog; is an accomplished performer having appeared in both France and Germany; had been examined by animal welfare organisations and a permit obtained for her inclusion in the exhibition.

Human comes and goes with her handler as she pleases – she is never required to be in the gallery at any particular time. If she decides to go for a walk, to eat or to rest, she does.

Not quite consent, but clearly the world of contemporary art is providing Human with a far better life than she might otherwise have faced; all that is expected of Human is to just be, albeit in the confines of the white cube of the museum.

Some interspecies art projects are motivated by a desire to enhance animal welfare. In a collaboration between Utrecht School of Arts and Wageningen University in the Netherlands, artists, scientists and game designers produced a videogame: Pig Chase in which a moving ball of light appears on a touch screen in a pig’s stall, remotely controlled by their human playmate. Once the pig nudges the ball it sets off coloured sparks and pig and human can team up with scores awarded for synchronised movement between snout and manoeuvred light ball.

As Seth Dunipace, animal welfare scientist, observed: while Pig Chase might offer the farm animal a welcome distraction, boredom being a problem for penned animals, the activity also endears the pig to their playmate as if it were a pet, a domestication that somewhat misrepresents the pig’s ultimate fate.

So who does care for the animal in art? Reactions to live animals in contemporary art are likely influenced by a discursive setting where “freedom” rests with the artist, and both audience and animal are part of an artistic experiment.

Where that experiment takes place in a research institution such as a university, both artist and animal welfare scientist must comply with strict ethics processes but even then the framing of a project motivated by artistic inquiry may appear very different to one directed at animal welfare — even if the experience of the animal is no different.

While the notion of the aesthetic alibi, a protective shield frequently raised in support of confronting art, may continue to offer a particular freedom to how artists work with animals, artists working as researchers in institutions face much tougher ethical compliance restrictions. Similar restrictions can also exist for curators; whose commitment is not only to the integrity of the artist but also to the exhibiting institution. Ants and spiders rarely evoke empathy but one wonders how audiences might have responded had Human inhabited the museum and grounds of TarraWarra during the Pierre Huyghe exhibition.

These are the questions that a University of Melbourne, Office of Research Ethics and Integrity funded project Trust Me I’m an Artist seeks to address.

Today at 5.30pm Peta Tait, Victoria Lynn and Seth Dunipace, together with Kate MacNeill will engage in a discussion ROLL UP: animals, ethics and art, details here. Pierre Huyghe: TarraWarra International 2015 is on until November 22, details here. Huyghe’s latest film Untitled (Human Mask) will screen at ACMI on October 19, details here.