What is culture? In today’s globalized world, we are familiar with seeing various cultural objects and ornamentation outside of their original location or context.

If culture is not fixed and bound to a particular location, how does culture move and transform?

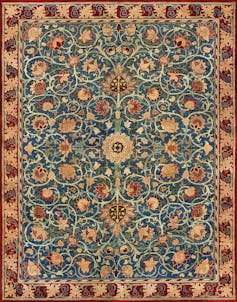

Ornamentation in Islamic art — patterned decoration or embellishment seen on objects or in architecture — is a great example of such movement of culture that can now be found across the world.

Throughout the centuries, Islamic geometric patterns and arabesque (Islimi) designs — otherwise known as biomorphic, floral patterns — have moved from east to west.

These patterns have been built upon and adapted, and as such may not even be recognized as bearing the imprint or influence of Islamic societies.

Islamic art influence on western design

For example, the 19th century English designer William Morris — renowned for patterning that became known in fabrics, furniture and other Arts and Crafts movement decorative arts — was inspired by the biomorphic floral designs of the Islamic arabesque (Islimi) ornamentation.

A recent exhibition, Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity, at Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris showcases the influence of Islamic art on the designs of French jewelry designer Maison Cartier.

What is fascinating about this exhibition is the paring of jewels and precious objects with the artifacts from Islamic lands such as a 14-15th century Iranian mosaic tile that were the original sources of inspiration for Cartier. This exhibition travels to the Dallas Museum of Art in May 2022.

‘Cultural translation’

Part of the reason for this movement of culture is the mobility of people and the portability of ornamental objects.

The notion of “cultural translation,” coined by cultural theorist Homi K. Bhabha, is the act of translation, which is neither one cultural tradition nor the other cultural tradition, but is the emergence of other positions. The root of the English word translation is from the Latin translatus meaning “to carry over” or “to bring across.”

Movement resulting from migration gives rise to people’s acts of cultural translation. Translation is the negotiation arising from encounters of two social groups with different cultural traditions.

For Bhabha, cultural difference is never a finished “thing.” Migrant experiences exist at the borders or edges of different cultures and are in flux. Consequently, people’s acts of translating language or visual signs and symbols is an act of constant negotiation between cultures.

In this process, the migrant’s struggle operates in a process of transformation in the in-between space of cultures called the third space. The third space is a hybrid space of negotiating cultural interactions.

Muslim artists in diaspora

A good example of these kinds of cultural negotiations happens in the works of contemporary artists from culturally diverse backgrounds living in the western societies (in diaspora).

For Muslim artists in diaspora, traditional Islamic art forms contextualize their connections to their cultural backgrounds within broader social, political and cultural concerns — concerns like migration, cultural identity and diversity.

Pakistani Canadian artist Tazeen Qayyum uses the language of the traditional Islamic ornamentation in her work such as A Holding Pattern (2013) in order to investigate what it means to live between two cultures.

Upon first glance, the viewer perceives an aesthetically pleasing geometric design reminiscent of arabesque tile works in Islamic architecture. However, a closer inspection reveals that the ornamental pattern is a repetition of cockroaches’ silhouettes.

In a recent article for BlackFlash magazine, Qayyum explains this work:

“I also intricately painted a set of airport lounge chairs representative of the liminal space of an airport, where migrants and refugees are neither here nor there but instead wait for clearance upon arrival at Pearson Airport. The title ‘holding pattern’ solidifies this thinking as it connotes an aircraft awaiting clearance to land. It is a state of waiting that references my own displaced identity of living between two cultures, always in transit and never truly at home.”

‘In-between space’

Contemporary cultural theorists, such as Sara Ahmed and Bhabha have argued that such artists enter a mode of cultural translation.

Artists destabilize the idea of a monolithic culture and instead construct works that are influenced by locations of cultures that reflect an “in-between space”: a site of dialogue reflecting these interconnected influences.

I recently created artwork in which I investigate cultural translation and question displacement, dissemination and reinsertion of culture by re-contextualizing culturally specific ornamentation. This work is for a three-person exhibition, The Art of Living: On Community, Immigration, and the Migration of Symbols, Jude Abu Zaineh, Soheila Esfahani, Xiaojing Yan, curated by Catherine Bédard, at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris (opening May 12, 2022).

In my work Mallards Reeds, a vintage wooden sign depicting a flock of Canada geese and mallards flying over a marsh at sunset has been laser-etched with an arabesque pattern.

By placing the arabesque design on the wood cutout of Canada geese and mallards — a vintage “Canadiana” object — I aim to question the origin of culture and the role of ornamentation. I acquired this object at a local company where I live in Waterloo Region, Ontario, that salvages and reclaims wood materials. At one time, the sign apparently hung at a restaurant.

This pattern is replicated from sections of the mosaic design of the interior dome of the Imam Mosque in Isfahan, Iran.

This mosque, also known as the Royal Mosque, is part of a complex of buildings in an urban square designated as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization world heritage site.

Experiences, cultures inform readings

As art historian Oleg Grabar notes in his book The Mediation of Ornament: “ … ornament is the ultimate mediator, paradoxically questioning the value of meanings by chanelling them into pleasure. Or is it possible to argue instead that by providing pleasure, ornament also gives to the observer the right and the freedom to choose meaning?”

My work aims to become a mediator allowing the viewer to enter the third space and hinges on an act of negotiation. The viewers’ unique experiences and cultures inform their reading of the work. This allows them to “enter the third space” by engaging in cultural translation: viewers carry their culture across and onto the work of art and vice versa.

I am interested in the notion of the third space not only in contemporary art/culture, but also as a means of opening a space of dialogue across fields of study in order to mobilize multiple perspectives.