The Convergence Review Final Report released yesterday appears at first blush to promise major changes to the Australian media landscape.

The report flags the creation of a new communications regulator and classification system, a new system for financing Australian content production, a new approach to spectrum management, and a new public interest test for changes in media ownership.

All of these recommendations were foreshadowed in the Review’s Interim Report, released in December. On the basis of that slim volume, I argued then that the review promised a dramatic shift in Australian media.

While I still think that if these changes are enacted (and that is not a small “if”) the media landscape will look very different in the future. Now with the benefit of more detail in the final report, I am not so sure that this belongs to the same forward-looking policy vision.

What’s important?

Media reporting of the Convergence Review has concentrated on the headline proposal to create a new regulatory body.

But for the majority of Australians this is a side issue. For my part, it is not entirely clear why a brand new regulator is needed at all.

The recommendations around Australian content on the other hand will be of most obvious and immediate interest to the general public.

For an unspecified transitional period, the commercial free to air (FTA) broadcasters will still have to meet the existing quota of 55% Australian content. The quotas for Australian drama, documentary and children’s programming will be increased by 50%, although the additional programming can be spread across all of the FTA’s digital multi-channels.

The review proposes that for the first time, the ABC and SBS will be required to screen minimum amounts of Australian content – 55% and 22.5% respectively. The 10% minimum expenditure requirement on subscription television drama channels will be maintained for the moment, and augmented by a similar requirement for channels screening mostly children’s and documentary programs.

In radio, much to the relief of the local music industry, the rules requiring analog radio stations to play certain amounts of Australian music will be retained and expanded to cover digital services.

Aussie content problems

Unlike radio, content quotas on free to air television are to be phased out. In their place, the Review proposes a new system for financing content production.

But without quotas it will no longer be guaranteed that large volumes of Australian content will be made available on a free-to-view basis.

In fact, the review contains no provision to facilitate the distribution of either traditional or new Australian content. Unlike production, distribution will be left to market forces.

While it may seem reasonable to assume that media companies that are required to fund production will make that content available, it is no longer certain that Australian content will be widely distributed, or that current volumes will be maintained, let alone increased.

Slipping through the net

The major change in the final report relates to the proposal to shift the burden of funding Australian content from broadcasters to “content service enterprises” (CSEs).

CSEs are defined in the Interim Report as all groups who “provide audio-visual content, whether linear or non-linear”. But the final report narrows this definition dramatically.

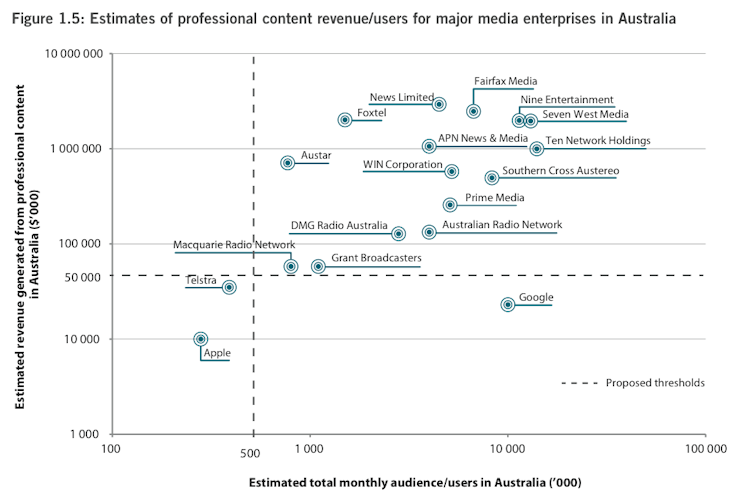

Now only “the most substantial and influential media groups” will be categorised as CSEs. To qualify as a CSE, the Review suggests thresholds of around $50 million a year of Australian-sourced content service revenue and audience/users of 500,000 per month. This new definition means only 15 or so groups will be required to produce extra Australian content.

This captures companies that previously had no Australian content requirements, such as Fairfax Media and News Limited. But it deliberately excludes major players like Telstra, Google, Apple, Facebook and Internet service providers. Telstra and Google are excluded because, as this helpful graph baldly illustrates, they fall just outside the thresholds of revenue and scale that will define a CSE.

Lobbied changes

Frankly, this is extraordinary – how on any measure can Telstra and Google not be regarded as “substantial and influential”?

But it is hardly surprising given these companies’ vigorous lobbying in recent months. Google even went so far as to commission research showing that while it facilitated enormous amounts of Australian content on YouTube – the ubiquitous Natalie Tran was namedropped again – it could not be considered to “control” the content.

Google, through its YouTube Original Channels and content partnership programs, and Telstra through its half-ownership of Foxtel, its BigPond Movies and its online services, are indisputably major media groups.

And if, as was suggested in this report, Telstra may be in the market for a range of media acquisitions, it will soon become an even more significant market player.

If not now then…

Hopefully the Review is simply putting these companies on notice. Letting them know that while they will not receive a bill for Australian content tomorrow, it is inevitable that as their services grow they will soon be defined as CSEs and so liable to content regulation in the future.

The Interim Report suggested that the new regulations requiring financial support for Australian content production be implemented “as soon as practicable” for those CSEs “that do not use broadcast spectrum”.

This clearly suggests that the Review was anticipating that the scheme would capture a wide range of entities. But in the final report, all of the fifteen entities likely to be designated a CSE with three exceptions (Foxtel, News Limited and Fairfax Media) are existing users of broadcasting spectrum, and all have their origins and power bases in traditional media.

Missed opportunity

The Final Report does contain a number of specific proposals to foster new content and services. But in many ways it focused too heavily on traditional media.

The majority of new production funding will still go to traditional forms of (professional) screen content, and the burden of regulation will still fall most heavily on radio and television broadcasters.

While the government has committed to respond to the Review, no timeline has been provided. Given the fragility of the Parliamentary numbers, it is possible that the government will not want to risk picking any more fights and could ignore the report entirely.

In coming weeks, the major media players will no doubt pick apart the recommendations for a new regulator and a public interest test for media mergers, neither of which garnered much industry support during the Review.

For most participants though, the key issue was Australian content regulation. For me, the final report raises as many questions as it answers on this. I cannot help but feel that greater weight was given to the interests of the major media companies at the expense of the broader public interest.

An opportunity has been missed to establish the policy grounds on which innovative Australian content and new services might flourish in the future.