Prime Minister Tony Abbott visited a P-TECH (Pathways in Technology Early Career High) school in New York last week, hinting it’s a model of education we should consider implementing in Australia. The school, partly funded by IBM and training students to suit the company’s needs, is different to anything we have in Australia. While the P-TECH model would be feasible here, the model risks confusing economic needs with educational ones.

The P-TECH model in the US

The approach taken by P-TECH has generated a lot of interest since it was opened in 2011. It already has a name, the P-TECH model, and is being copied in cities around the US. New York State, for example, has developed partnerships for a further 16 schools like the original.

The P-TECH model sounds a little confusing at first: both private and public money is used to fund high schools that also give university degrees. P-TECH schools are situated in low socio-economic areas and have a stated aim of helping students to become “job ready” for a particular sector of employment that has a shortage of workers. Existing schools in the US have focused on training for the technology sector and new schools are also looking to train workers for manufacturing and health care.

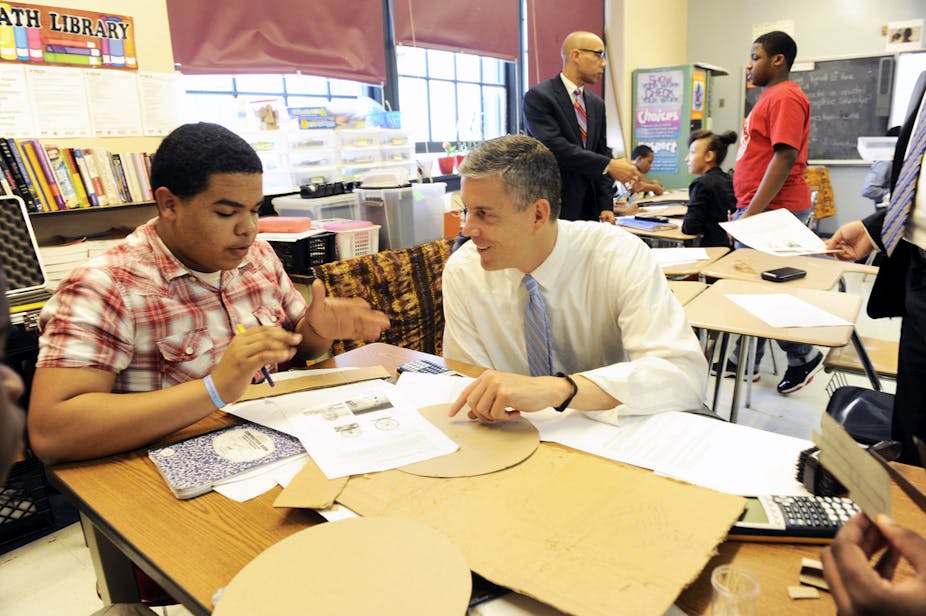

The school that Abbott visited, for example, was funded by the NYC Department of Education, the City University of New York and the private company IBM. The school goes for two years beyond the equivalent of our Year 12. Graduates receive corporate mentoring during their study, an associate degree in technology (similar to a diploma) upon graduation, as well as a job interview with IBM.

Politicians in particular are big proponents of the P-TECH model because it looks like a win-win situation. The nation’s economy gets a supply of workers in sectors where there are perceived shortages. The private business entering into the partnership gets positive publicity and a supply of qualified labour. The state gets to have the cost of education significantly subsidised by private enterprise. And the student gets a qualification for the cost of just two years’ extra study.

While the ideas in these schools are not new, their integration in the P-TECH model is generating a buzz in the US to the point that the latest version in Chicago made the front page of TIME magazine. The question is now being asked whether the model might have a place in Australia.

Is it feasible in Australia?

While we don’t have anything like the culture of philanthropy seen in the US, businesses see this model as much more of an investment (in publicity, recruitment and training) than charity. There would likely be interested parties, especially given the huge positive coverage received by IBM in the US.

The challenge for implementing these schools is in the grey area they occupy between high schools and universities. In Australia, only accredited institutions can award degrees. Any P-TECH type school would require either accreditation or exemption – this would be difficult for a school to obtain without significant political willpower.

Perhaps more to the point, it is difficult to see the need for schools that give degrees in Australia, where the separation of school and further education still serves the needs of both students and the national interest.

Does the P-TECH model have educational merit?

We’ve been talking about a new type of school, yet still have not mentioned educational value. This is partly because the first cohort at P-TECH hasn’t graduated yet so not much is known about outcomes. Yet we can consider likely implications.

Those arguing for these schools point out the advantages to students in gaining employment and higher starting salaries. This comes from an unstated belief that the goal of education is to create graduates who meet the economic needs of the country, and that those graduates can thus fulfil their own need for gainful employment. From this perspective there is no problem with inclusion of private companies in educational partnerships.

The view of the PM is typical of this notion of education:

What we want to do is ensure that youngsters are getting an education which is relevant to their needs and that we are investing in education and training systems that are going to have appropriate economic pay-offs for our country.

What this perspective neglects is that the next generation has needs much broader than gaining employment and being a part of the economic life of the country. For example, they need to leave school with the ability to think critically, to have the broad range of skills for leading a fulfilling and creative life - no matter their circumstances. This view is summed up by Richard Shaull in his foreword to educational theorist Paulo Freire’s book:

Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity, or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.

The P-TECH schools, with their involvement of the private sector and focus upon vocational training, are likely to be a step backwards in achieving this. It is entirely possible for these schools to succeed in their own terms and achieve high rates of graduate employment, yet still to fail their students.