For many countries, vaccine programmes have been one of the great triumphs of the pandemic. But in South Africa, it’s a very different story. To date, fewer than 5% of South Africans have been vaccinated, and the country is now in the grips of another COVID-19 surge as the delta variant takes hold.

This puts a focus on the country’s vaccination failures – of which there have been many, says Shabir A Madhi, professor of vaccinology at the University of Witwatersrand.

South Africa didn’t start trying to buy vaccine doses until too late and has been towards the back of the vaccine queue, which has led to a shortage of supplies. It has also struggled to roll out the vaccines that it has. In mid-June, a third of its supplies still sat unused, a sign of poor logistical planning and that its electronic vaccination system had failed to reach all groups across the population.

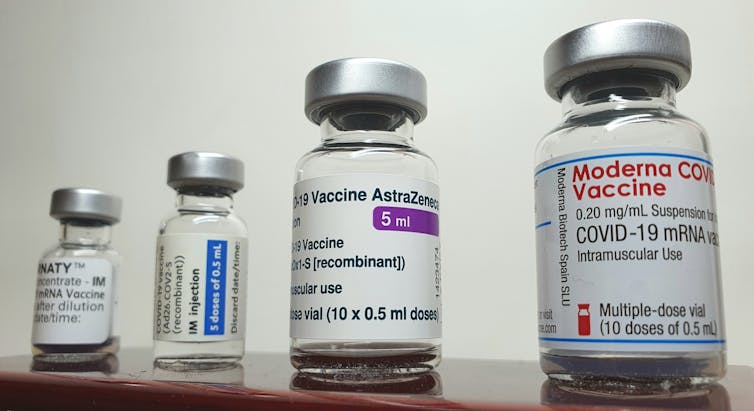

But perhaps South Africa’s greatest error was with the AstraZeneca vaccine, which it stopped rolling out on the basis that it didn’t protect well against mild to moderate disease caused by the beta variant previously dominant in the country. Despite the World Health Organization saying South Africa should continue distributing the jab, as it would probably still protect against severe disease, the government instead sold 1.5 million doses to other African countries.

That decision, which followed a study led by Professor Madhi on the effectiveness of the AstraZeneca vaccine against the beta variant, now looks like a massive error. Not using those doses has set back South Africa’s rollout, and it is now facing delta – which the AstraZeneca vaccine performs well against – becoming the dominant variant.

Over the past few months, our weekly roundups have looked a lot at vaccine hesitancy, production bottlenecks and procurement problems. But now, South Africa has shown that there’s another factor that can severely undermine the success of vaccine rollout: a government not having faith in the products at its disposal. Hopefully others won’t make the same mistake.

This is our weekly round-up of expert information about the COVID-19 vaccines.

The Conversation, a not-for-profit group, works with a wide range of academics across its global network to produce evidence-based analysis and insights. Get more regular updates from trusted experts by subscribing to our free newsletter .

It has become clearer than ever that people need to take their second vaccine dose in order to minimise their chance of developing COVID-19. After two doses of either the Pfizer or AstraZeneca vaccine, the chances of getting ill or being hospitalised aren’t much different today than they were when the alpha variant was dominant, explains Rebecca Aicheler, senior lecturer in immunology at Cardiff Metropolitan University. But with only one dose, you’re now much more likely to develop COVID-19 than before.

And delaying the second vaccine dose, as the UK chose to do, was the right move, argues Paul Hunter, professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia. It allowed the good protection offered by a single shot to be given to more people at a time when cases were high and the vulnerable had little protection.

Yes, it may have since left single-dosed people more exposed to delta, but even without full protection, their chances of developing serious COVID-19 are low after having one jab. The real failure of the British government regarding the delta variant was in not doing enough to stop it coming into the country.

Finally, up until now it’s been UK policy that your second vaccine dose should be the same as your first – but in time, that may change. Early results from an ongoing study suggest that mixing doses – giving people a first made by one manufacturer and a second from another – can result in better overall immunity, writes Tracy Hussell, professor of inflammatory disease at the University of Manchester.

Following AstraZeneca with Pfizer looks to be particularly good, leading to high levels of antibodies but also a very strong T-cell response. As the UK and other countries start to consider booster programmes, it may be that they decide to mix up what people get for their third doses.

Get the latest news and advice on COVID-19, direct from the experts in your inbox. Join hundreds of thousands who trust experts by subscribing to our newsletter.