If you were called “woke”, would you take it as a compliment or an insult?

This simple question sums up a lot about the “culture wars” that have become such a focus in the UK in the last couple of years. Only relatively small proportions of the public have engaged in the debate, but those that have often have utterly different perspectives.

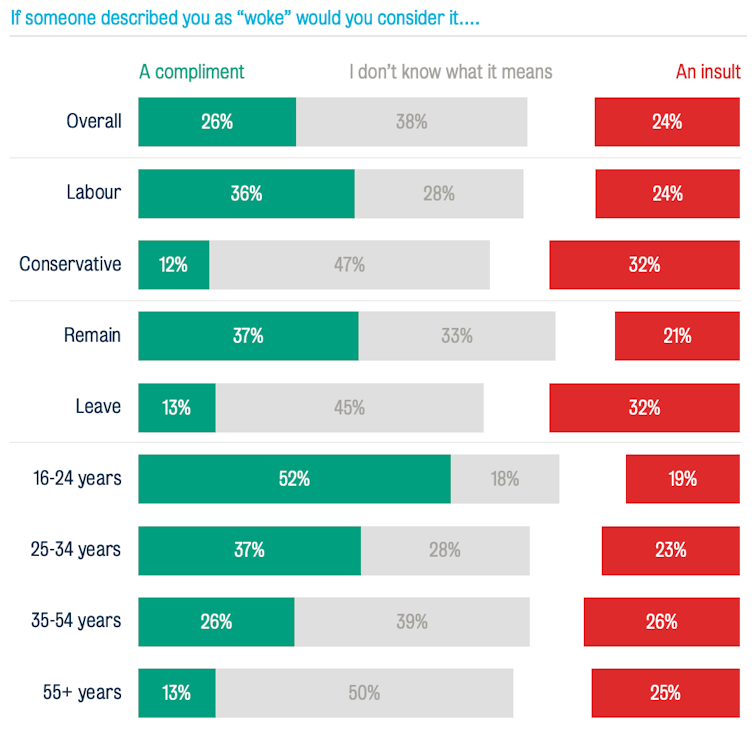

Our major new study suggests the public is completely split on the matter, with a quarter saying it’s a compliment, a quarter that it’s an insult – and the rest having little clue what the term even means.

Where people stand on these divides depends a lot on their characteristics. In particular, 52% of the young think the term woke is a compliment, compared with just 13% of those aged 55 or over. And Labour supporters are three times as likely as Conservative supporters to think of it as a compliment.

Of course, when thinking about how to interpret the term, answers don’t just depend on your age and political leaning - they also depend on how it’s being used. This is a further feature of the culture war debate and source of public confusion - the same terms often have very different meanings to each side.

Where does the idea of culture wars come from?

The language of “culture wars” was first popularised by the US sociologist James Davison Hunter in the early 1990s. Hunter used it to describe the deep-seated tension that had emerged in the US between “orthodox” and “progressive” worldviews. For him, the term not only captured a political struggle over cultural issues, but also “a heightened awareness of culture itself and those who seek to shape it” – a conflict “over the meaning of America”.

A “culture war”, in this fuller definition, signals much more than disagreement. In Hunter’s conception, it describes a sense of conflict between two irreconcilable worldviews in what is “fundamentally right and wrong about the world we live in”.

In the UK, however, the culture wars term has been attached to all sorts of disparate issues in media coverage. Perhaps partly because of this, its meaning remains of little interest or salience to the public. When people were asked to describe, in their own words, what sorts of issues the term “culture wars” made them think of, by far the most common response was that it didn’t make them think of any.

And only tiny minorities associate culture wars with many of the stories that have been prominent in UK media coverage: just over 1% link the term to the Black Lives Matter movement or debates over transgender rights, while under 1% make a connection to the removal of statues.

Indeed, looking across our whole research programme on culture wars, the clear impression is that the public is much less engaged or extreme in its views than you’d suspect, given the explosion in political and media discussion of the culture wars.

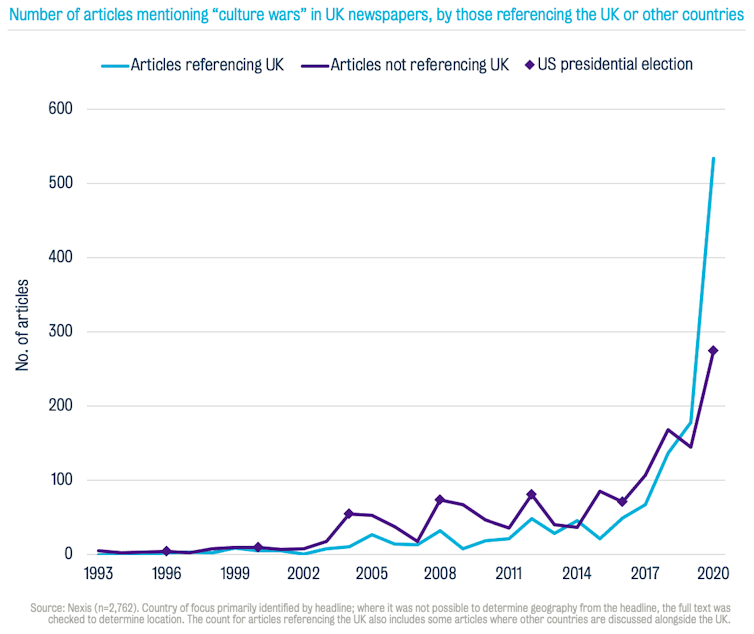

In 2015, there were just 21 articles in the main UK newspapers and news-sites that talked about “culture wars” in our own country. Last year, there were 534. The timing of this exponential surge in media coverage in the UK seems to point to Brexit as a trigger. But while the cultural divisions that Brexit revealed and reinforced have certainly played a key role, it’s far from the only, or even the main, focus now.

In fact, the top issues that the media talked about as part of the culture wars in 2020 were empire and slavery, race and ethnicity, our response to COVID-19 and party politics. Brexit was down at ninth in the list.

Sections of the media have, then, clearly imported the US language and concepts of culture wars wholesale – but it’s much less clear whether the public is as invested in the discussion.

Can we call off the culture war?

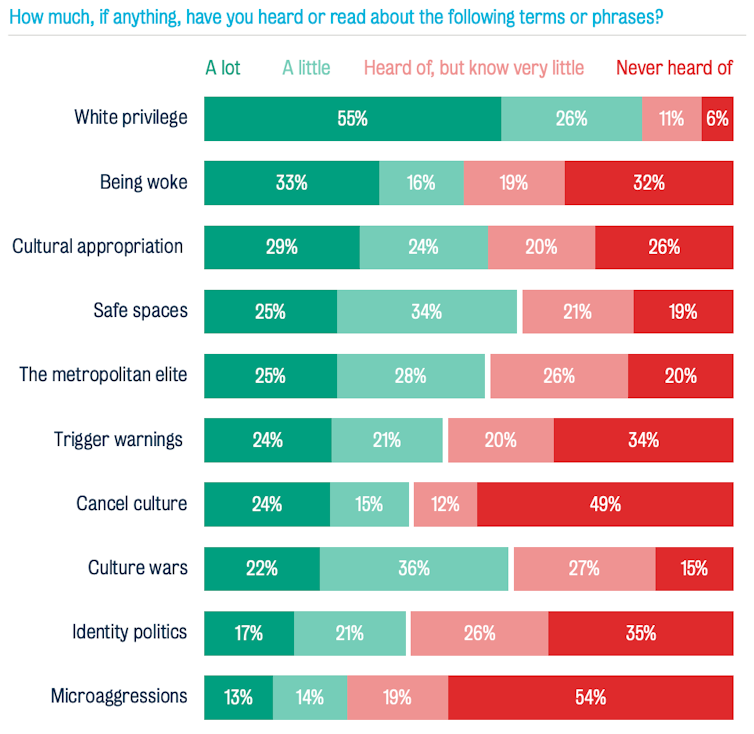

Across a whole series of terms connected to the culture wars, the majority said they’d heard at best “a little” about them, with large proportions saying they’d never heard of common media and political tropes such as “cancel culture” and “microagressions”.

The one term that has cut through more is “white privilege”, with over half of the UK public saying they’d heard a lot about it. This is not a good thing for those interested in making the case for a continued focus on racial equality, as other recent research shows the public are pretty sceptical about the term, particularly white groups. For example, half of white British people agree that it’s easier to get ahead if you’re white, but only 29% agree there is “white privilege” in Britain. The language used and framing of debates matters.

But while it’s good news that the UK public is too sensible or distracted to get caught up in this rhetoric as yet, it would be a mistake to relax. The US history of culture wars suggests we’re at a very dangerous moment. The tone and focus of political leaders, activists and the media undoubtedly matter, as the US experience shows. The public are not passive recipients of messages from on high, but political and media discussions can be catalysts that encourage division.

Where America leads, Britain often follows – but we can still choose a different path.