The ongoing controversy about the effectiveness of the New South Wales government’s lockout laws and their impact on Sydney’s nightlife is part of a broader pattern in the city’s history.

Since the earliest days of British colonisation, authorities have sought to limit the problems associated with alcohol by licensing its sale and limiting the times and places where it is drunk. But, ironically, this kind of regulation has helped to create precisely the violent, misogynistic and law-breaking drinking culture that it was intended to control.

The struggle to license pubs

The British convicts, military and officials who first established Sydney came from a society in which drinking was ubiquitous and the pub was central to everyday life, but the social elite hypocritically condemned drunkenness.

The first governor of NSW, Arthur Phillip reflected these two views when he said, in 1792, that providing a supply of alcohol to the settlement:

… may be necessary but it will certainly be a great evil.

By the end of his time in NSW, Phillip was forced to issue the first liquor licences in a vain effort to reduce the booming trade in smuggled rum.

Successive governors struggled and failed to control this trade. Officially licensed pubs had strict conditions on their licences, including orders to close at the nightly curfew of nine o’clock. But drinking continued in the many sly-grog shops (unlicensed liquor stores) whose owners brazenly flouted the curfew by bribing police.

The problem of illicit sale was eventually solved through a combination of looser rules – including longer hours – and more professional police to enforce them. But this early history reinforced a culture of police hostility to drinkers and publicans, which remains to this day.

Temperance and the Sabbath

By the late 1830s pubs were open until midnight. Liquor was widely available; indeed this was probably the peak era of alcohol consumption in Australia’s history.

But Sydney’s drinking culture was transformed by temperance, the 19th-century’s largest social movement.

Temperance was an international, organised and popular campaign against alcohol, which it saw as the root cause of social ills. It began in efforts to persuade drinkers to pledge abstinence. When this failed, advocates turned to government, lobbying for strict limits on access and aiming for total prohibition.

Sabbatarianism was a closely related movement to preserve a pious Christian Sunday. Campaigners sought to prevent people from working or engaging in frivolous or immoral activities like visiting pubs or even museums on the Sabbath.

Sabbatarians also fought to enforce sobriety during Christian holidays. If you have ever wondered why you can’t buy takeaway alcohol on Good Friday, this is why.

This broad moral crusade targeted drinking in general, and late-night drinking in particular. Temperance alliances, formed in each colony, were among the most successful lobby groups in colonial politics. They eventually won the right to “local option” – a policy whereby each electorate could vote to increase or reduce its number of licensed premises.

This policy’s legacy is clearly visible in modern Sydney. Inner-city areas, once dominated by working-class voters, have far more current and former pubs than the respectable middle-class suburbs.

Six o’clock closing

The movement’s greatest success in Australia came in 1916 with the introduction of six o’clock closing.

Amid wider calls for wartime austerity, campaigners seized on a drunken riot among soldiers training for the front and persuaded the NSW government to hold a referendum on closing hours. A majority voted for the earliest hour of six o’clock.

Once the war ended, the policy’s full impact became clear. With most workers finishing at five and pubs shutting at six, the hour between became known as the six o’clock swill, as drinkers struggled to consume as much as they could before closing time.

Once again, repression led to deviance. Sly-grog houses proliferated and crime flourished.

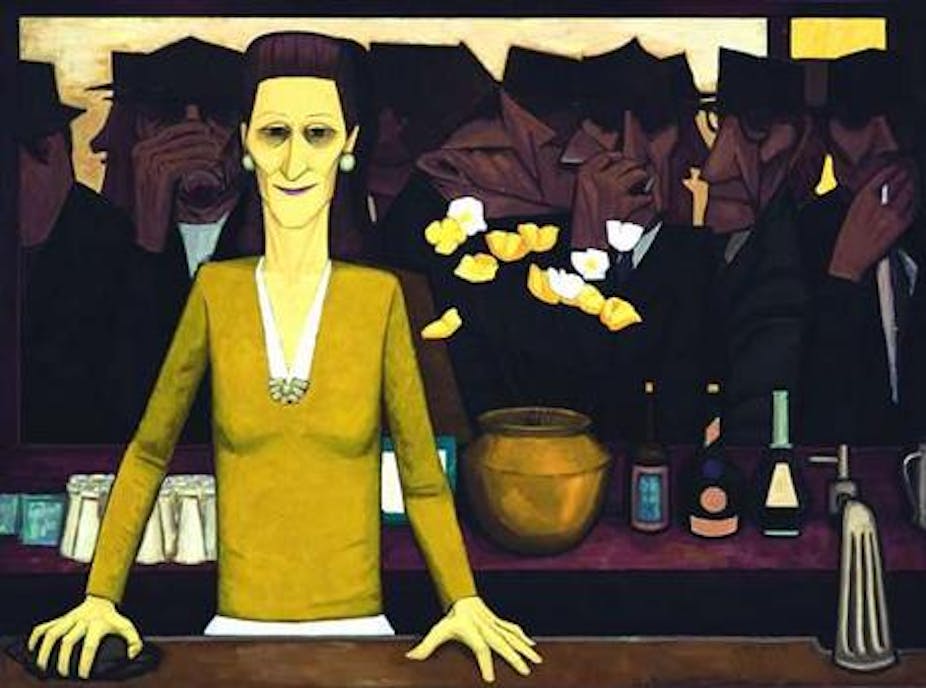

Just as importantly, the swill helped consolidate segregated drinking. Respectable women avoided and were increasingly excluded from the “public” bar, which became a male space. Women who wished to drink in public were forced into dedicated “ladies lounges”.

After six o’clock

Six o’clock closing lasted for half a century across most of Australia. But, by the 1950s, there were growing calls for its repeal. The growth of mass tourism and post-war immigration exposed more Australians to other drinking cultures and highlighted the unnecessary problems associated with the swill.

Following a 1954 referendum, NSW extended opening hours until ten o’clock. They have steadily expanded since.

But the legacy of earlier restrictions remains visible in reduced Sunday trading and the regular calls for stricter limits on drinking time. There is a clear cycle of media attention, public outcry and government enthusiasm about the ongoing problem of alcohol-related violence, which seems to lead invariably to calls for further controls on drinking.

In the short term, such policies may well be effective, though the recent results in Sydney are at least debatable. But, viewed in light of this broader history, why does it matter when we drink?