How can we see what we are imagining but still see what’s in front of us? – Malala Yousafzai class, Globe Primary School, London, UK.

This question gets right at the heart of a big issue for brain scientists. Say you’re daydreaming in class – you can have your eyes open and be aware of the colours and shapes in the classroom and the movement of your teacher and classmates, while at the same time “seeing” whatever you’re thinking of or imagining.

These two kinds of seeing are quite different, but they both happen in the same part at the back of our brain – the visual cortex. Messages coming from different places can cause the visual cortex to become active, and whenever that happens, you “see” things.

To understand how this happens, imagine that you are a brain. You’re locked up inside a skull – a dark, silent vault. You’re in charge of a body, and you somehow need to know what’s going on in the world around you in order to guide this body successfully.

Curious Kids is a series by The Conversation, which gives children the chance to have their questions about the world answered by experts. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskids@theconversation.com. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our very best.

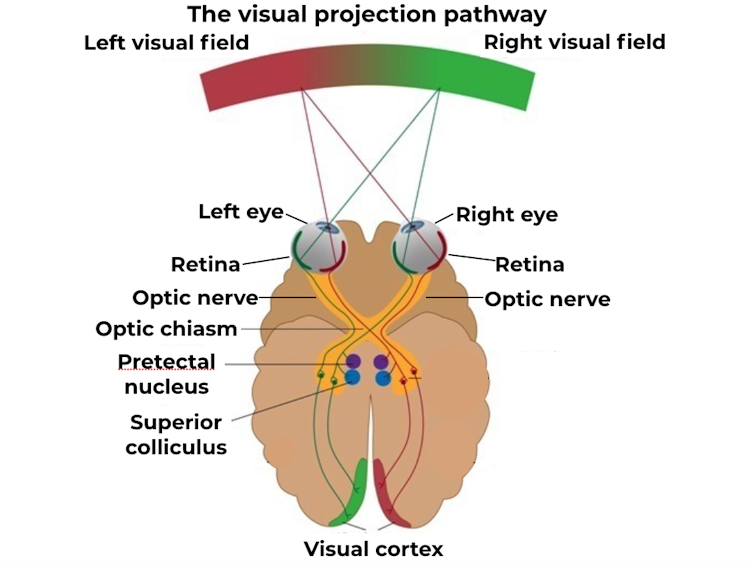

One place the messages can come from is your eyes: light bounces off the objects around you and enters your eyes (if they’re open). The light is then focused onto the retina – a thin layer of light sensitive cells on the back of your eyeball.

The cells in the retina then send messages through the optic nerve, back towards the visual cortex. There, different parts of the visual cortex get to work decoding colours, edges and outlines and movements and faces.

The brain then puts all those visual messages back together again, allowing you to see what’s around you.

Imagining things

Remember, as far as the brain’s concerned, it doesn’t really matter where the messages are coming from – when the visual cortex is active, you are seeing.

So the messages could also be coming from other parts of your brain – and this is what happens when you see the things you imagine, remember or dream.

For example, sometimes hearing a song can make you remember where you were the last time you heard it. The sound can cause a cascade of activity in the brain: messages go from the parts of the brain that hear, to the parts that remember and eventually to the parts that see – and that’s how you experience a memory.

Patterns and predictions

That explains how your brain manages two different ways of seeing. But it takes a lot of energy for your brain to see what’s going on around you, based on the messages it gets from your eyes. So there’s another trick the brain uses for seeing, to help save itself some effort: it tries to predict what’s about to happen, based on your past experiences.

Even before babies are born, they’re already learning about the patterns that exist in the world. As babies get older, they learn from these patterns to predict what’s going to happen next.

For example, the first time a baby sees her dad goes around a corner, she might think he’s disappeared, and get upset. Then, when dad comes back, the baby might be surprised and happy.

But after this happens a few times, the baby starts to expect that her dad will come back from around the corner, and won’t be surprised anymore.

Balancing act

So, your brain is actually making up what you see all the time, based on messages from different places, as well as your expectations.

The brain keeps a delicate balance between these messages and expectations, to help guide you through the world, while also saving energy.

So if the teacher calls your name while you’re daydreaming in class, your brain quickly switches from imagining things, to paying close attention to the messages coming from your senses about what’s going on in the classroom.

Children can have their own questions answered by experts – just send them in to Curious Kids, along with the child’s first name, age and town or city. You can:

- email curiouskids@theconversation.com

- tweet us @ConversationUK with #curiouskids

- DM us on Instagram @theconversationdotcom

Here are some more Curious Kids articles, written by academic experts: