When a living treasure like David Hockney visits our shores, it might be tempting to hold a blockbuster retrospective. Instead, the NGV, in collaboration with Hockney’s studio, has chosen to comprehensively explore Hockney’s works of the past decade.

This reflects the fact that Hockney continues to be a prolific picture-maker, constantly evolving and incorporating new mediums into his artistic oeuvre. The NGV exhibition boasts a huge collection of Hockney’s digital drawings, as well as photography, video works, and paintings.

Hockney has neither rested on his substantial early laurels, nor is he currently quite the innovator he is frequently labelled as. The technology that allows one to draw on the iphone and ipad is available and widely used even by children, and I find it slightly patronising and ageist to suggest that merely by engaging with this technology, Hockney is an innovator.

Where Hockney is innovative and pivotal in current artistic discourse is in his ongoing explorations of perspective, time and space – themes he has explored throughout his career through a variety of artistic mediums, often embracing new technologies.

Hockney first drew on a room-sized computer in 1986, waiting two minutes for the lines to appear. Since then, he has used faxes, photocopiers, Xerox machines and polaroids, before adopting the iphone in 2009, and then the ipad in 2010.

Embracing these latter with the exuberance of a digital native, he has created thousands of artworks, memos, emails and greeting cards (although I’m not quite sure why so many cards and emails are displayed in this exhibition).

He has also used digital technology to help construct what is possibly one of the largest en plein air paintings ever completed, Bigger Trees near Warter, comprising 50 oil on canvas panels. Donated to the Tate in London, it now occupies a huge wall in the NGV, flanked by two reproductions on paper on the adjacent walls, designed, apparently, to create an “immersive experience”.

Although the experience is immersive, it owes little to the addition of the copies. The huge painting becomes immersive because it is impossible to take it in at a glance. The eyes must scan back and forth, and up and down, even when standing back. Walking along the image, moving through the landscape and continually adjusting your view, facilitates a lived experience in both time and space.

This meticulous exploration of time and space unifies this somewhat disparate and visually overwhelming exhibition. Hockney claims that painting will never be replaced by photography because the slick, flat surfaces and frozen instants of time in photographs do not represent the reality of what the constantly scanning eye sees (try showing a photo to a dog – it won’t recognise the subject matter).

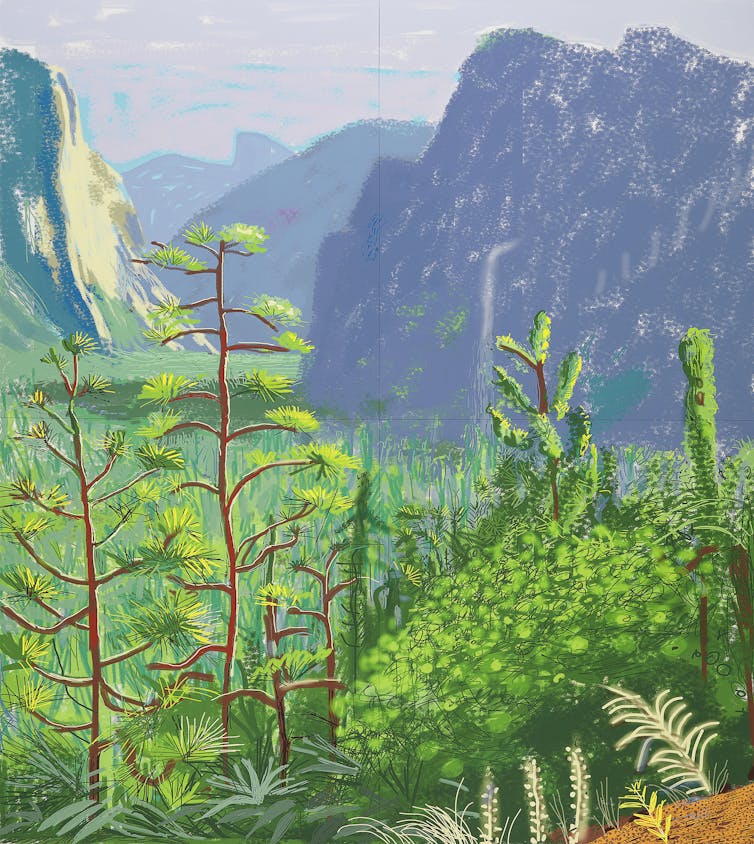

Two series of digital drawings, Yosemite (National Park in California), and The arrival of spring in Woldgate (the Yorkshire landscape), show the landscapes as constantly in flux, blooming, cascading, puddling and filled with ever-changing light.

Hockney has used the Mac facility for “playing back” the drawing to highlight the passage of time by animating the process of the creation of the piece, showing his landscape come to life over time.

Many of the Yorkshire landscapes feature roads leading off into the distance or through natural archways of vegetation. When reproduced at large scale, the eye journeys down the roadways and meanders through the trees at the side. The animations enhance this, the flickers of movement caused by emerging details catching the eye and pulling it around the picture plane.

Another immersive installation, The Four Seasons, Woldgate Woods, articulates this theme further. A darkened room houses four large panels, each with nine high-definition video screens. A car rigged with nine video cameras, all set at slightly different zooms and angles, was driven slowly through the Woldgate landscape, capturing an identical trip in each of the four seasons.

Displayed simultaneously on panels placed around the room as if at the cardinal points, the idea is simple. But the result is mesmerising and soothing, forcing you to step back from your hectic routines and contemplate the notion of movement through open space and cyclical time from which we are increasingly alienated and dislocated in the contemporary world.

A further highlight with a genesis in a tragic death is 82 portraits and 1 still life, comprising 82 acrylic on canvas portraits of Hockney’s family, friends and associates. Viewed by Hockney as a single work, each portrait is the same size with a similar coloured background, all sitters occupying the same elevated chair.

The works are displayed chronologically in an elongated room that must be circumnavigated to view them. By controlling the major elements of location, Hockney invites us again to contemplate both space and time.

Over the precisely three days of sitting, each sitter came to own and claim the space uniquely and each portrait is vital and brimming with character. The importance of time is highlighted in the title of each piece which, along with the name of the sitter, records the dates of the sitting.

Talking to NGV director Tony Ellwood, Hockney emphasised that both people and trees are individuals. I was initially taken aback at these seemingly self-evident remarks.

But perhaps in our alienated and disconnected world, where life is increasingly experienced through the camera lens of the phone and ipad, we need to be reminded of nature, trees, the passage of time, shifting perspectives and to live life with exuberance.

David Hockney: Current is at Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria until 13 March 2017