The May long weekend is the unofficial start of summer. And for those of you with home gardens or access to community space, this is the weekend to dust off your gardening tools and visit the garden centre for the growing season ahead.

As we approach the start of gardening season, it’s good time to ask some questions about its origins.

Whether you plan to get marigolds, plant a vegetable garden or create a pollinator patch — all gardens have complicated roots.

In fact, the practice of gardening is deeply tied to colonialism — from the formation of botany as a science, to the spread of seeds, species and knowledge.

In this episode of Don’t Call Me Resilient, we explore the complicated roots of the garden, including who gets to garden. We also discuss practical tips about what to plant with an eye to Indigenous knowledge. We speak with researcher Jacqueline L. Scott and also chat with community activist, Carolynne Crawley, who leads workshops that integrate Indigenous teachings into practice.

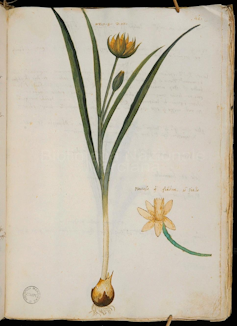

Coveted tulips

Some of the most recognizable plants today, such as tulips, are the result of early colonial conquests. Originally found growing wild in the valleys where current China and Tibet meet Afghanistan and Russia, tulips were first cultivated in Istanbul as early as 1055.

Later, after they were hybridized and commodified by the Dutch, they became highly coveted status symbols because of their gorgeous, but fleeting, blooms.

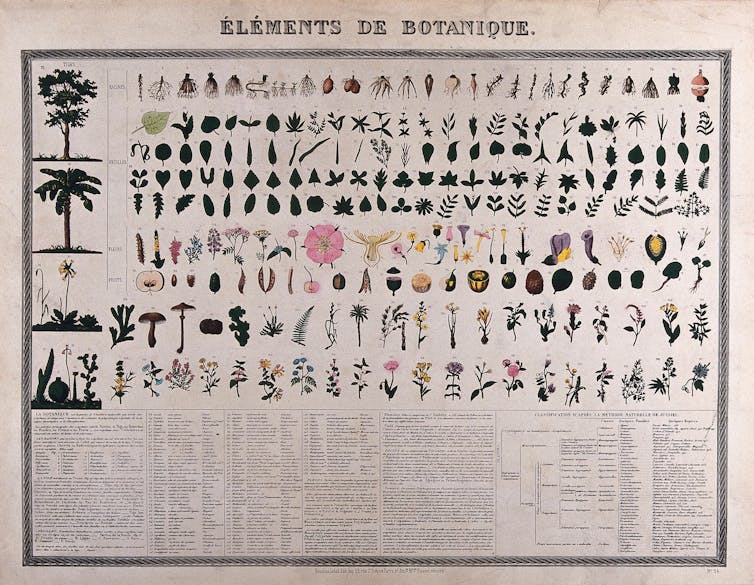

Exploratory botanical voyages by colonial European powers were integral to the expansion of empire. These trips fueled the big business of collecting global plant samples and also led to the emergence of botany as a scientific discipline.

Botanical gardens served as labs

Botanical gardens played a key role, serving as the laboratories where plant specimens were organized, ordered and named. “Scientific objectivity” asserted a Eurocentric point of view, disrupting and displacing Indigenous Knowledge and ecological practices.

The movement and transfer of plants around the world went hand in hand with the transportation of people to provide a labour force, through slavery and indentured servitude.

The plantation system cleared out local ecosystems and replaced traditional farming methods with growing cash crops — like sugar-cane, tea and cotton. These were products meant for European curiosities, markets and profit and not for the local populations.

Plant and racial hierarchies

This colonial system of organizing agriculture laid the groundwork for categorizing people in a similar way, establishing a social hierarchy which dehumanized non-Europeans, helping justify slavery and Indigenous genocide, and eventually leading to racial categories.

This history has shaped our current relationships to the land, and our gardens. It also informs beliefs about land ownership and access; who has a right to enjoy the land, versus who is expected to be working on it. Who has the literal and figurative space and freedom to garden?

Shifting attitudes

But the soil is shifting. There is a growing shift away from the colonial status symbol of the lawn and manicured gardens, in favour of pollinator-friendly native plants.

There is also a growing understanding that centuries-old Indigenous land-based knowledge and practices — like controlled burns — can help manage wildfires, and foster a more resilient landscape.

With concerns about our climate crisis growing, one of the possible avenues for creating more sustainable cities may very well lie in our gardens.

Could we have an impact simply by thinking a little differently about the seeds we sow and the “weeds” we pull?

Listen and Follow

You can listen to or follow Don’t Call Me Resilient on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to your favourite podcasts.

We’d love to hear from you, including any ideas for future episodes. Join The Conversation on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok and use #DontCallMeResilient.

Resources

Tiffany Traverse on seeds and their endless power to give, heal and grow - Canada’s National Observer

The coloniality of planting: legacies of racism and slavery in the practice of botany - The Architectural Review

The Long Shadow Of Colonial Science - Noema Magazine

Is it time to decolonize your lawn? - Globe and Mail

Turtle Protectors in Toronto’s High Park

Spring joy with Ateqah Khaki - Gardening Out Loud

From the archives - in The Conversation

Read more: How the colonial past of botanical gardens can be put to good use

Read more: Director of science at Kew: it's time to decolonise botanical collections