More Australians are renting their housing longer than in the past. But they have relatively little legal security against rent increases and evictions compared to tenants in other countries. When state governments suggest stronger protections for tenants, landlords and real estate agents claim it will cause disinvestment from the sector, increasing pressure on already tight rental markets.

In research for the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), published today, we put the “disinvestment” claim to the test. We looked at the impacts of tenancy reforms in New South Wales and Victoria on rental property records over 20 years, as well as surveying hundreds of property investors. We found no evidence to support this claim.

We did find a high rate of turnover as properties enter and leave the sector. This happened regardless of tenancy law reforms. It’s a major cause of the unsettled nature of private rental housing for tenants.

We suggest that if substantial tenancy reforms did cause less committed landlords to exit the sector, that might not be a bad thing.

Read more: If your landlord wants to increase your rent, here are your rights

How did we test the disinvestment claim?

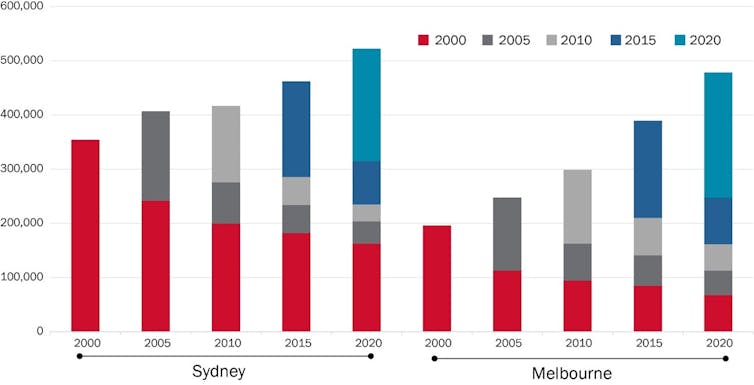

We analysed records of all rental bond lodgements and refunds in Sydney and Melbourne from 2000 to 2020. From these records we can see properties entering the rental sector for the first time (investment) and exiting the sector (disinvestment).

We looked for changes in trends in property entries and exits around two law reform episodes: when the 2010 NSW Residential Tenancies Act took effect, and the start of a tenancy law reform review in Victoria in 2015.

We found no evidence the NSW reforms affected property entries (investment). And property exits (disinvestment) were slightly reduced – that is, fewer properties exited than expected.

In Victoria, we found property entries reduced slightly when the law reform review started – perhaps a sign of investors pausing for “due diligence”. We saw no effect on property exits.

So in neither state did we find evidence of a disinvestment effect.

We also surveyed 970 current and previous property investors, and got a similar picture. When deciding to invest, investors said prospective rental income and capital gains were the most important considerations, but tenancy laws were important too.

On the other hand, tenancy laws were the least-cited reason for disposing of properties. Many more investors said they did it because they judged it a good time to sell and realise gains, or they wanted money for other purposes, or because the investment was not paying as they had hoped.

Read more: How 5 key tenancy reforms are affecting renters and landlords around Australia

A state of constant churn

Our research also gives new insights into the private rental sector, which has been growing relative to owner-occupied and social housing.

Small-holding “mum and dad” landlords dominate the sector. Some 70% of landlords own a single property. Multiple-property owners own more properties in total, but still relatively small numbers (rarely more than ten) compared to corporate landlords in other countries who have tens of thousands of properties, or even more. Australia now has some large corporate landlords, but their properties are a tiny fraction of the total rental stock.

Beneath its gradual growth and persistent small-holding pattern, the private rental sector is dynamic. Properties enter and exit the sector very frequently. In both Sydney and Melbourne, our analysis shows, most properties exit within five years of entering.

More than 30% of tenancies begin in a property that’s new to the rental sector. And more than 25% of tenancy terminations happen when the property exits the sector.

Our investor survey also shows the sector’s dynamism. Many investors made repeated investments, owning multiple properties and some interstate. They indicated strong interest in short-term letting, such as Airbnb, and significant minorities had used their properties for purposes other than rental housing.

Australia’s rental housing interacts closely with other sectors, particularly owner-occupied housing, as houses and strata-titled apartments trade between the sectors. The tax-subsidised property prices paid by owner-occupiers heavily influence investors’ gains and decision-making. Rental is also increasingly integrated with tourism, through governments’ permissive approach to short-term letting.

In short, the Australian rental sector is built for investing and disinvesting. As properties churn in and out of rental, renters are churned in and out of housing.

This presents problems for tenants.

A new agenda for tenancy law reform

Australian residential tenancies law has accommodated the long-term growth of the rental sector and its dynamic character. With no licensing or training requirements, it’s easy for landlords to enter the sector. It’s also easy to exit by terminating tenancies, on grounds they want to use a property for other purposes, or even without grounds in many cases.

Over the years tenancy law reform has fixed some problem areas, but with virtually no national co-ordination. Laws are increasingly inconsistent on important topics, such as tenants’ security (for example, some states have restricted, but not eliminated, no-grounds terminations), minimum standards and domestic violence. Reforms have overlooked significant problem areas, such as steep rent increases and landlords’ liability for defective premises.

It is time to pursue a national agenda that goes further than previous limited reforms. The focus should be on the rights of tenants to affordable housing, in decent condition, that supports autonomy and secure occupancy.

Where landlords say it is too difficult and they will disinvest, this should not be taken as a threat. Indeed, it would be a good thing if the speculative, incapable and unwilling investors exited the sector. This would make properties available for new owner-occupiers and open up prospects for other, more committed landlords, especially non-profit providers of rental housing.

Similarly, if we had higher standards and expectations to discourage private landlords from entering the sector, that would open up scope for new owner-occupiers and investors who are less inclined to churn properties and households.

While past tenancy law reforms have not caused disinvestment, maybe the next reforms should.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their research co-authors, Professor Kath Hulse, Professor Eileen O’Brien Webb, Dr Laura Crommelin and Liss Ralston.