On Monday, to much fanfare, astronomers working with the Kepler space observatory (which was launched in March 2009) announced their first discovery of a planet orbiting within the “habitable zone” of its host star. The planet in question, Kepler-22b, is far from a twin to Earth (even describing it as “Earth-like” is likely pushing things a little far), but the result is still a striking one – and it’s likely to be the first of many.

Searching for moths around distant candles

The Kepler spacecraft searches for planets around other stars using the “Transit Method”, looking for the small tell-tale dips in a star’s brightness that occur when a planet orbiting that star passes directly between Earth and its host. For such transits to occur, the orbit of the planet in question must be perfectly aligned such that the planet passes between Earth and its host. Even if the orbit is tilted by just a small amount from the planet, it will pass unseen “above” or “below” the star, as we look at it, and no transit will occur.

To put the challenge facing astronomers looking for transits into context, imagine for a moment standing outside on a perfectly clear night, far from any source of light pollution, looking up at the night sky. If you’ve allowed time for your eyes to become properly adapted to the dark, you’ll probably be able to see roughly 6,000 stars.

If every single one of those stars had a telescope pointing towards our sun, capable of detecting transits of Earth, only 30 of them would be correctly aligned, and would see transits. For the rest, the transit method would offer no evidence Earth exists.

In other words, if you want to find planets using the transit method, you need to survey a huge number of stars to maximise your chances that at least some of them will have transiting planets.

And if you want to find Earth-like planets (those that could have liquid water on their surface, and therefore potentially be habitable), you need to observe those stars continually, for a long period of time. Since Earth takes one year to orbit the sun, it would only transit once per year.

But one dip in a star’s brightness does not a planet make, so you really need to observe at least three transits before you can have any confidence that what you’re seeing is truly a planet.

That’s exactly what Kepler is doing.

Investigating the habitable zone

Kepler has produced a vast amount of information over the past two years, continually observing almost 150,000 stars, and the scientists working with it are trying to find particularly exciting planets to announce. This has already led to a number of astounding discoveries.

In February last year, Kepler announced the discovery of Kepler-11, a planetary system with six transiting planets packed so closely together that the furthest from their host star was half the distance Earth is from the sun. And in September this year, the Kepler team announced Kepler-16(AB)b, a planet with two suns.

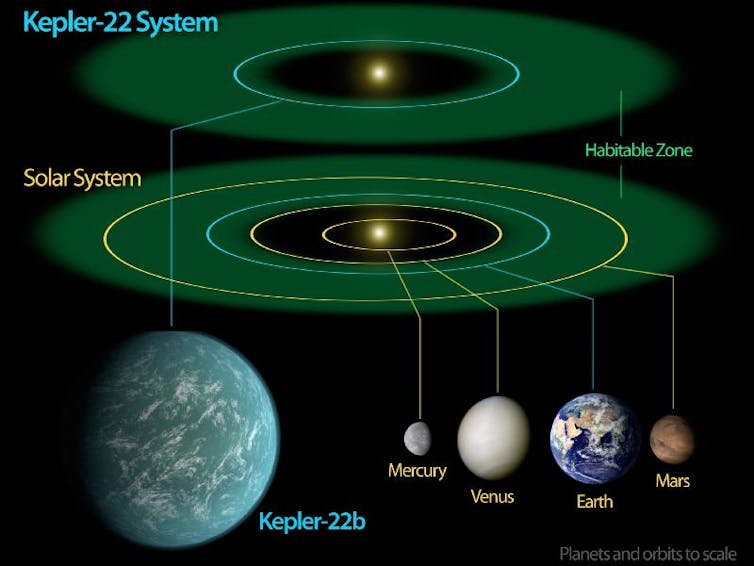

On December 5th, as the centrepiece of the latest suite of Kepler announcements, the discovery of Kepler-22b, right in the “habitable zone” of its star, was announced. The “habitable zone” is the range of distances from that star at which a planet’s surface would be, theoretically, just the right temperature for liquid water to exist.

The above image shows the orbit of Kepler-22b and that of the four terrestrial planets in our own solar system, by way of comparison. In the solar system, Venus is too close to the sun to lie in the habitable zone. It can be seen from this diagram that Kepler-22b lies at a distance somewhere between Venus and Earth, meaning that it could have liquid water on its surface.

Earth 2.0?

Kepler-22b orbits a star very much like our own, albeit slightly less massive, and a little less luminous (which means that the habitable zone lies a little further in than in our own solar system). The star itself lies approximately 600 light years from Earth, making it around 150 times more distant than Proxima Centauri, the sun’s nearest neighbour. Astronomically speaking, although that isn’t quite in our backyard, it’s certainly in our neighbourhood.

The planet orbits its host star over a period of 290 days, and has only been discovered so quickly with Kepler because the first transit we could observe fell very soon after the start of the mission, meaning there has been time for the planet to complete two full orbits of its host star, and hence allow us to observe three transits.

Without the observation of the third transit, this planet would be just another of the 2,300+ candidates awaiting confirmation. The fact it has been found so soon is certainly a slice of good fortune.

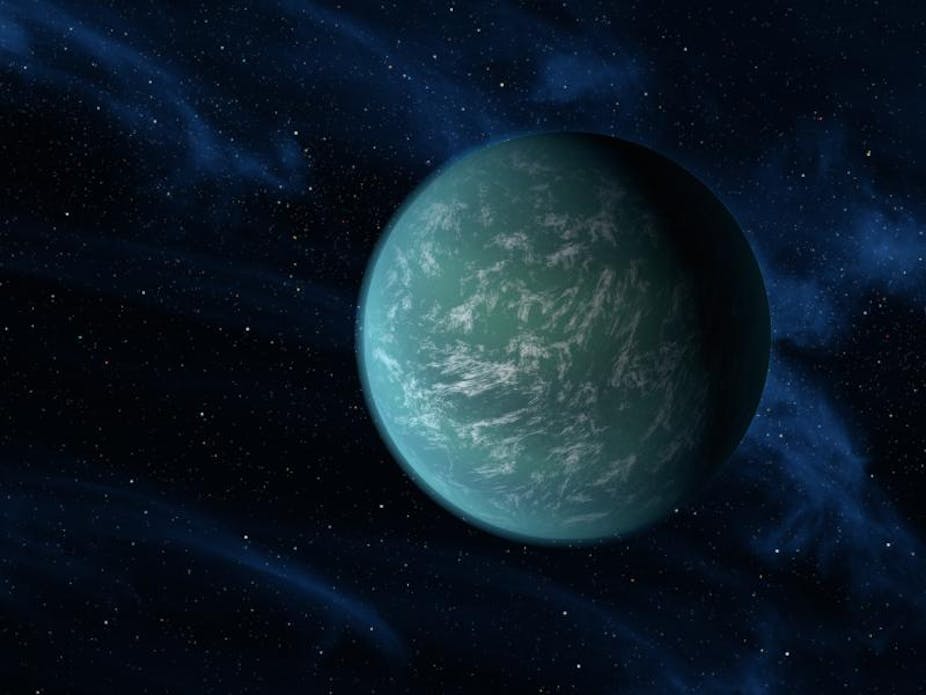

Despite all the fanfare, Kepler-22b is certainly nothing like Earth. Transit observations don’t allow us to “weigh” a planet, but they do allow the size of the planet to be determined (a bigger planet blocks more light, causing the star’s brightness to dip by a great amount). Kepler-22b, it turns out, is around 2.4 times the radius of Earth.

That’s roughly half way between the size of Earth and the size of Uranus and Neptune, the solar system’s ice giants. It’s most likely, therefore, to be a “super-Earth”, far more massive than the Earth, and probably has a thick atmosphere. It might well have a rocky crust somewhere beneath that atmosphere, but it’s hard to be sure.

NASA scientists have calculated that the temperature at Kepler-22b’s surface could be a balmy 22°C – which sounds remarkably clement (the average temperature of the Earth’s surface, by comparison, is around 15°C, though without the beneficial effects of the Earth’s greenhouse, it would be closer to a frigid -20°C).

But given Kepler-22b’s mass, it may well have a significantly denser atmosphere than the Earth, which, in turn, probably means the true surface temperature will be higher than the optimistic 22°C mentioned above. Indeed, if the atmosphere of the planet is sufficiently dense, and rich in greenhouse gasses, it might well be more like Venus than the Earth, with a surface far too warm to house liquid water.

A sign of things to come

Given the uncertainties, it’s premature to consider Kepler-22b a habitable, Earth-like planet. But the detection of the first Kepler planet to lie comfortably within the theoretical habitable zone of its host star is still very exciting.

Kepler has been carrying out observations for long enough now that at least some potentially-habitable worlds will have transited their host stars the minimum of three times required for firm detection – and the longer the satellite goes on observing, the more transits by such planets will be observed.

In this context, the announcement of Kepler-22b isn’t actually a huge surprise – it merely shows Kepler’s observations are running on schedule. Where one planet is found, more are certain to follow, and it’s almost guaranteed that, somewhere among the 2,326 potential planets announced by the Kepler team yesterday, many more “habitable” planets have already been detected and are simply awaiting confirmation.