Can you believe it’s been a year already? I’m sure we all remember where we were when we heard the terrible news we’d lost Gregg Jevin.

You know, Gregg Jevin? The Gregg Jevin?

Don’t worry if the name doesn’t ring any bells. There never was a Gregg Jevin. Yet he “died” on 24th February last year, in a tweet from British comedian Michael Legge:

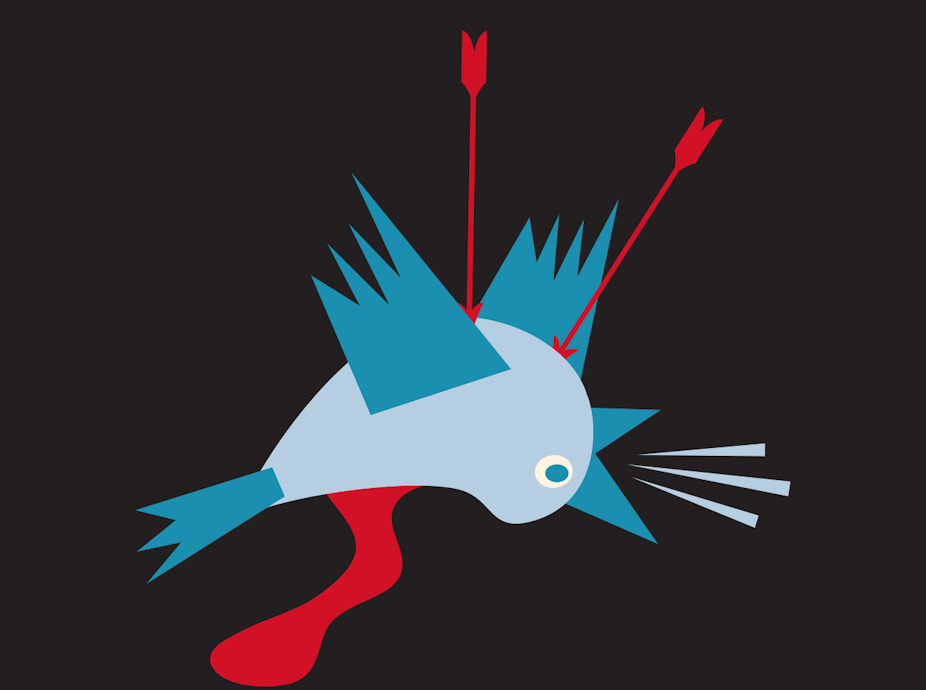

Sad to say that Gregg Jevin, a man I just made up, has died. #RIPGreggJevin

— Michael Legge (@michaellegge) February 24, 2012

Within hours, #RIPGreggJevin was trending on Twitter, with celebrities, companies and ordinary punters rushing to express “condolences”. Some of it was genuinely hilarious. Even the odd philosopher had a go at it.

The Jevin affair suggests something genuinely interesting about “Twitter mourning”: we’ve been doing it long enough that it’s developed its own conventions, which users know how to satirise when given the chance. I’m sure it’s no coincidence that Legge’s tweet went viral only days after Twitter’s outpouring of grief for Whitney Houston. The “death” of Gregg Jevin briefly gave people a sandbox in which to play around with the language of online mourning without causing genuine offence.

Now, just when we’d somehow managed to pick up the pieces and move on without Gregg, a startup called _LivesOn claims it will change the way Twitter users interact with the dead.

Details are scant, but the idea seems to be that the service will use an algorithm to generate new tweets of behalf of dead users, tweets that sound like those the user themselves posted in life. The net effect is that, as _LivesOn put it, “When your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting.”

It’s hard to know how seriously to take these claims. Representatives of _LivesOn deny being a publicity stunt, describing itself as an project jointly conducted by an ad agency and a university. But even if it’s deadly serious (sorry), commentators have questioned whether the technology could possibly deliver what it promises.

This is not the first time a company has held out the prospect of perpetuating an online presence after your demise. Intellitar’s “Virtual Eternity” service – currently closed, supposedly for further development – offers an animated avatar that can interact with users, using artificial intelligence to “answer” questions as you would have done. The results, frankly, aren’t impressive, at least not yet.

The interesting point is not whether these technologies will ever be any good, but that they’re being discussed at all. What does it say about us that we’re reaching for this kind of digital immortality?

It seems silly to think you could somehow survive your death through a service that tweets on your behalf. But consider how much of our communication with others is now mediated through social media: might there be some sense in the idea that extending your online presence after your death would keep you in existence somehow?

Yes and no. In research published last year, I looked into the increasingly common practice of memorialising the profiles of dead Facebook users. For a large number of us, Facebook has become a large part of our presence in the lives of others. When Facebook users die, their digital traces persist; through them, the dead arguably do retain something of their presence in our lives. Perhaps that’s why people continue to post on the walls of dead Facebook users long after their passing.

So social media can, in one sense, help the dead remain with us. But why isn’t this thought much comfort?

To answer that, I suggest we consider some recent developments in the philosophy of personal identity. Discussions in this field have increasingly begun to differentiate between the “person” and the “self” (or in a slightly different version, the “narrative self” or “autobiographical self” and the “minimal self” or “core self”).

The distinction is applied somewhat differently by different theorists, but it goes roughly like this: the self is the subject you experience yourself as being here and now, the thing that’s thinking your thoughts and having your experiences, while the person is a physical, psychological and social being that is spread out across time.

One of the questions I focus on in my work is how these two kinds of selfhood interact, and the ways in which they can come apart. In this case, something like _LivesOn might in fact extend the identity of your person, albeit in a very thin and diminished sense. If you’re a regular tweeter, it might serve in some small way to enhance your ongoing presence in the life of other people.

But it doesn’t extend your self. There’s no experience to look forward to, no subject at the core of your tweets. Perhaps it helps you live on for others, to some small degree, but not for yourself.

So perhaps we shouldn’t hope for too much from our posthumous online presences. Perhaps we should leave posterity to worry about itself and simply live the best we can here and now.

It’s what Gregg would have wanted.