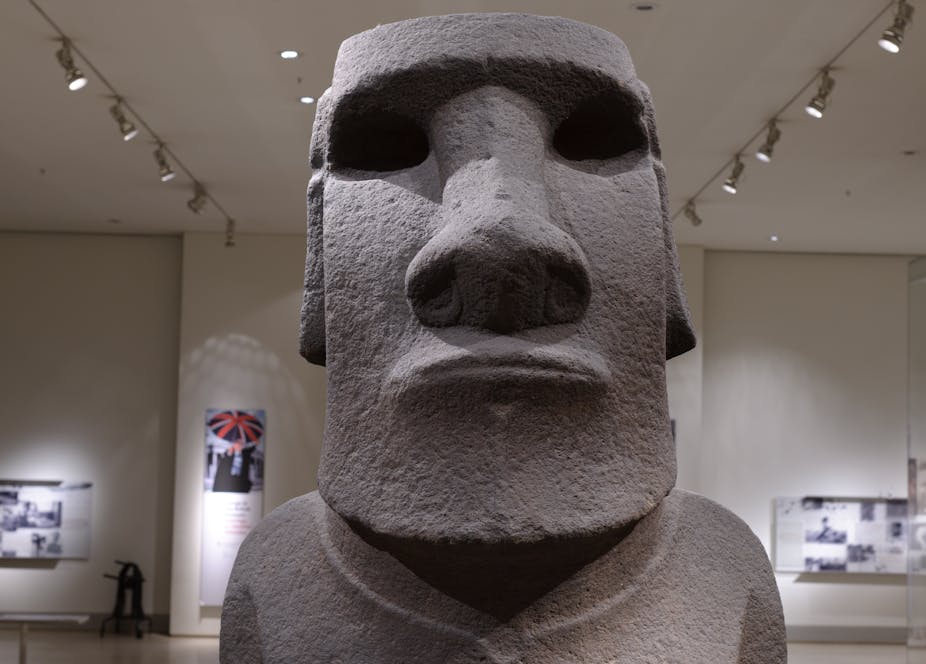

Standing tall at the entrance of the British Museum is the statue known as Hoa Hakananai’a. To the Rapa Nui, the indigenous people of Easter Island, it means stolen or hidden friend. He is one of the iconic Moai head carvings that made the south Pacific island famous. The Rapa Nui see the Moia not as mere carved basalt rocks but as brothers and sisters. They believe that the eyes in the statues carry the spirits of their ancestors, and provide protection to the people.

They consider Hoa Hakananai’a to be one of the most spiritually important Moai of all. He left Easter Island in 1868 when Captain Richard Powell, commander of the British frigate HMS Topaze, took him without permission. Powell gave the statue to Queen Victoria, who donated him to the British Museum. It has resided there ever since.

The Rapa Nui are now lobbying the museum to bring him back, having gained self-administration over their ancestral lands from Chile in 2017. But while the museum has said it would consider a loan request for the statue, it does not seem prepared to go further.

Both the British Museum and counterparts in continental Europe are increasingly under pressure to return thousands of artefacts taken during colonial times. Many museums seem sympathetic to returning human remains – the British Museum recently announced it was returning Aboriginal ash bundles to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, for example. But when it comes to giving back heritage objects, long-term loans are the usual offer.

Most museums hide behind their own conservation policies, arguing that “deaccession” – permanently removing an item – is prohibited. In the past, it was often difficult to mount a legal challenge against this position. Yet there are signs that international law may finally be moving in favour of the Rapa Nui and the many other indigenous peoples affected.

Existing law

There is not yet any binding international law on this subject, so indigenous peoples have mainly had to rely on the various non-binding multilateral treaties and declarations dealing with the illegal trafficking of cultural objects. The UN’s Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of the Heritage of Indigenous People, adopted in 1995, request that governments and international organisations help indigenous peoples to recover such objects. They should be returned “wherever possible”, particularly if they have “significant cultural, religious or historical value”.

The relevant treaties include the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property 1970, and the UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects adopted in 1995. The UNIDROIT convention specifies that the relevant court in the state with the object should order it to be returned if the requesting state either establishes that its removal significantly impaired the “traditional or ritual use of the object by a tribal or indigenous community”, or that “the object is of significant cultural importance”.

There are countless examples of these conventions producing results – either through museums such as the American Getty voluntarily following their requirements; through domestic challenges such as the case that China won in Denmark in 2008 to repatriate over 150 smuggled relics; or on the back of UN recommendations such as those that saw Germany return the Boğazköy Sphinx to Turkey in 2011.

The conventions have crucial legal weaknesses, however. Under UNIDROIT, for example, the time limits for recovering stolen indigenous cultural property are flexible, while the rules only apply to items stolen after the treaty came into force. UNIDROIT has also only been signed or ratified by a limited number of countries, including New Zealand, Italy and Spain – but not the UK. Also, only states can participate, making it harder for indigenous peoples to bring actions.

Two later UNESCO conventions from 2003 and 2005 remedy this latter issue by recognising and encouraging the active participation of indigenous peoples in safeguarding cultural heritage. Yet neither convention covers past appropriations. Meanwhile, the UK is not a party to the 2003 treaty and is party to the 2005 treaty only through EU membership, which is due to end in March 2019.

New avenues

Human rights law is playing an increasingly promising role in this area. The most comprehensive relevant instrument is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted in 2007. Article 11, for example, recognises such peoples’ rights “to practice and revitalise their cultural traditions and customs”. This includes an accompanied duty for states to “provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution” (meaning they would return the object).

Putting cultural heritage on the human rights agenda has been a welcome addition to the legal toolbox around indigenous cultural objects, but as with most international legal instruments, implementation remains a thorny issue. The case is getting stronger, however. In 2016, the UN Human Rights Council issued a resolution recognising the importance of preserving and protecting cultural heritage as an “indispensable element of human flourishing”.

More recently, France appears to be spearheading change. A recent report by two specialist scholars, commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron, urged changing French heritage laws to support the permanent return of African art taken without consent. It talks in terms of “colonial restitution” as a remedy for an infringement of the human rights of people whose cultural artefacts were taken away. If the French government follows up by overhauling its cultural heritage laws, it will be a major step forward.

International environmental law is also seeking to endorse the repatriation of indigenous cultural heritage. The UN Biodiversity Conference 2018, taking place in Egypt, has been considering adopting the draft Rutzolijirisaxik Voluntary Guidelines for the Repatriation of Traditional Knowledge Relevant for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity. These deal with the repatriation of the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples and local communities held by museums, botanical gardens and other facilities.

All this progress makes me cautiously optimistic about the legal basis for future claims in this area. It is still a long road ahead, but with the right endorsement and cooperation from national governments and some goodwill from museums, the process of repatriation can gain further momentum.

This is a question of moral decency, and it is not just about cultural attachés: we can all become ambassadors lobbying for the restitution of looted cultural objects. As the historian David Olusoga aptly argues, in post-Brexit times, making friends to repatriate stolen objects is a matter of self-interest. The likes of the Rapa Nui are owed an apology. Returning Hoa Hakananai’a would be the first step in a long process of peacemaking and healing.