Ed Miliband suffers from a split personality. When discussed in the abstract – in polls, on the street or in newspapers - the image conjured up is of a policy wonk who, like many politicians, is far from ordinary. The image of Miliband as a goofy Wallace from Wallace and Gromit has gained traction, and many voters struggle to relate to the Labour leader.

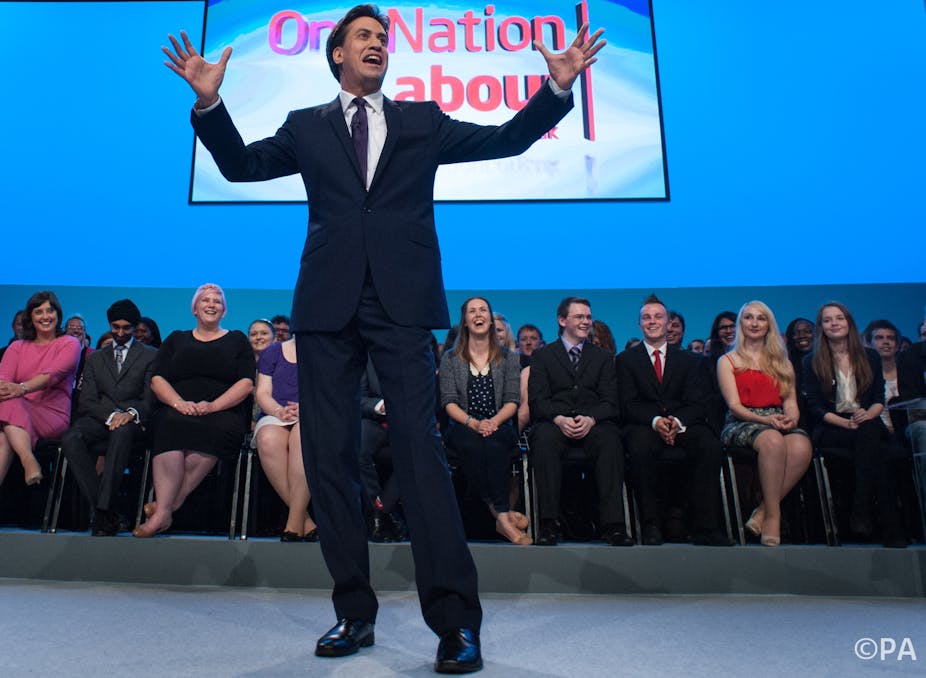

And yet, when people meet Miliband or hear him speak at length they change their opinions. We hear of the leader being a “decent man”, who is “genuine” and “intelligent” coming to the fore. It was this side of his personality that was communicated in his roundly praised 2012 conference speech, and which was again on show yesterday. Miliband even pointed to this dichotomy, opening his 2013 speech by quoting the crashed cyclist he helped earlier in the year, who described him as “not geeky at all” in person.

It may make for a good opening, but Miliband’s split personality poses problems for Labour. While the few people who have the chance to meet him, or the inclination to listen to his speeches, gain a favourable impression, most of the British public hold the former, negative image. This matters because it affects the public’s willingness to listen to Labour’s message, and accordingly damages their electoral chances.

It is well acknowledged that parties in opposition struggle to get media coverage and indeed a quick attempt to recall the key moments of David Cameron’s time as leader of the opposition illustrates this point. Hug a Hoodie, a husky trip to Norway, “compassionate conservatism” and the big society were some of the few ideas that have defined his leadership. Labour, on the other hand, will have sparse opportunities to communicate with voters, they must maximise on those chances.

In carving out space in which to present a distinctive policy agenda and message to voters, Miliband’s personality is therefore vital. He must appear at all times as a credible leader who can be trusted to implement his policy proposals and govern in the national interest. Yet only 12% of voters currently call Miliband a “strong leader” and 65% think he is doing badly as Labour Party leader.

In this light his speech was highly significant - it marked one of the few chances for Miliband to (re)define his personality. This is perhaps why he tackled his image problem head on, peppering his speech with rhetorical techniques designed to promote the positive side of his personalit. He spoke without notes, used humour, and made references to his family and the people he has managed to meet in person. Phrases like “not under my government” directly tackled his leadership credentials and he even said that if David Cameron wants “to have a debate about leadership and character, be my guest”.

By placing his personal leadership, if not at the centre, then as a key plank of his speech, Miliband took a risk. His address will be pored over by academics and political commentators alike, who will no doubt highlight his use of political oratory in re-framing his character, only fragments of the speech will be communicated to the public through sound bites on the 10 o’clock news and in newspaper headlines.

For this reason he is unlikely to counter the impression that he is “unconvincing”, “unelectable”, “weak”, “irritating” and “incompetent”. In fact it raises the issue of personality to the top of the agenda and in doing so risks compounding existing negative impressions. Unless Miliband can begin to change public attitudes about his personality, he will fail to win an audience for his ideas.