As someone addicted to the rhythms of BBC Radio 5 live every morning, it took me a few minutes to adjust to the seemingly new format of its breakfast show. Were it any other day, Nicky Campbell, Rachel Burden and assorted politicians and pundits would have faced my usual uninvited and scornful responses to their efforts to inform and educate.

As is the case with thousands of others, I suspect, the radio is my omnipresent, long-suffering sunrise companion, well used to absorbing all the self-righteous indignation a news junkie like me can muster when confronted by party spokespeople’s disingenuous platitudes.

But the morning of June 8 was different. The atmosphere was calmer, more measured; the human interest features had more space to breathe, as did the presenters. One particular item, on how fathers of children with severe autism coped with their lives, was genuinely emotive and enlightening.

Then it struck me. There was no argument, no dogma, no politicians at all, in fact, because it was polling day and on such days the BBC is simply not allowed to report the campaign or discuss party policy.

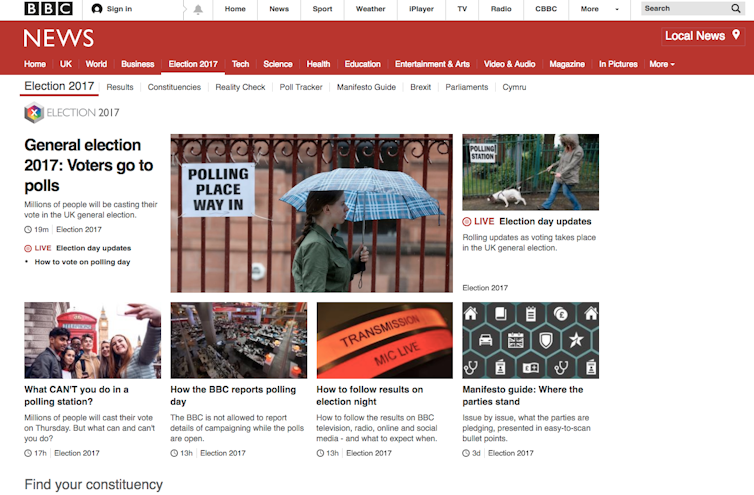

In common with all other broadcasters, the BBC has to adhere to a set of requirements which, as its code of practice states, means that from 12.30am until voting booths close at 10pm, no opinion poll on any issue relating to the election may be published or referred to. There can also be no coverage of any issues directly pertinent to the election campaigns on any BBC outlet or social media. In fact, it’s a criminal offence to publish an opinion or exit poll or details of how people may have actually voted until after the polls close. Predictions of any sort are strictly forbidden.

This is not to say there’s no coverage at all, though. If you’re interested in how the rain is coming down outside the voting station in Auchtermuchty, BBC News 24 has got you covered.

Keep quiet

It’s easy to be flippant, but – putting it rather grandly – these regulations are in place to ensure that the integrity of the democratic process is not compromised, and that no one party or candidate receives disproportionate coverage.

Newspapers, as is clear from the polling day front pages, have rather more leeway. Provided their stories go to press or are posted online before 12:30am on the big day, papers and news websites are effectively free to attempt to persuade their readers to vote in the way that best suits the proprietor’s – sorry, the public’s – interest.

But this is of course the age of social media, and the rules and regulations the broadcasters observe predate the digital age. What’s the point, one might ask, of subjecting the BBC et al to such restrictive practices when the internet is such a free-for-all?

The problem with that question is its assumption that behaviour online is not subject to the law on election day. As the Telegraph’s James Titcombe wrote on the big morning itself, the strict rules about publishing voting information before polling booths close also apply to the Facebook generation. Titcombe cites the Electoral Commission guidelines, which state that while one may reveal one’s own voting intentions online, tweeting or posting another person’s is not permitted.

Voters should beware the dangers of selfies, too. The commission “strongly advises” against taking any photographs at all inside polling stations. As Titcome intimates, images from inside this sacred democratic chamber:

… could jeopardise the secrecy of somebody else’s vote – they or their ballot paper could accidentally be captured – and taking a photo could be construed as an attempt to gain information about a vote.

All this aside, and writing as somebody with a (perhaps unhealthy) interest in political communication, I found the morning’s absence of electioneering positively invigorating. A few hours’ respite from Theresa and Jeremy and Nicola and Tim? Maybe it’ll catch on.