Though she is famed as one of England’s greatest writers, Emily Brontë – whose 200th birthday would have fallen on July 30, 2018 – probably only ever wrote one novel, Wuthering Heights, first published in 1847.

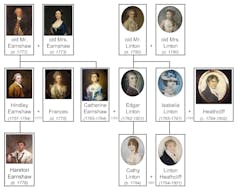

Wuthering Heights might now be synonymous with Cathy and Heathcliff, but their love affair is not the whole story. They exist within an elaborate web of semi-incestous relationships between the Earnshaw, Linton and Heathcliff families. Through its multigenerational story, the book examines whether grand but destructive passion is preferable to companionship and domesticity.

The novel’s first half relates the love between Cathy and Heathcliff, but the latter part is devoted to their descendants, especially Cathy’s daughter, Catherine Linton, and her nephew, Hareton Earnshaw. Ever since Wuthering Heights was first printed, the contrast between the two generations has prompted readers to ask the same questions. Does Brontë ultimately critique Cathy and Heathcliff’s exciting but tortured affair by comparing them with Catherine and Hareton? Or do the younger couple, after their transgressive predecessors, represent the restoration of boring convention?

Generations of patterns

From the very start, Wuthering Heights encourages readers to look at the generations in relation to one other. Brontë employs an intricate pattern of repeating names, a pattern made explicit by the bumbling narrator Lockwood. In an early chapter, Lockwood spends a night at the gothic Heights where he discovers those names graffitied onto a window ledge. He recounts:

This writing, however, was nothing but a name repeated in all kinds of characters, large and small – Catherine Earnshaw, here and there varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and then again to Catherine Linton.

In vapid listlessness I leant my head against the window, and continued spelling over Catherine Earnshaw—Heathcliff—Linton, till my eyes closed; but they had not rested five minutes when a glare of white letters started from the dark, as vivid as spectres – the air swarmed with Catherines…

This Catherine soup foreshadows major events to come. The first Catherine, Cathy, begins the novel as “Catherine Earnshaw” before taking the surname Linton after marrying Edgar. Her daughter is born “Catherine Linton” then becomes “Catherine Heathcliff” through a forced marriage to Linton Heathcliff, Heathcliff’s son. In the final chapter, the second Catherine is engaged to Hareton and is on the verge of being renamed “Catherine Earnshaw”. As the names reveal, the novel gives one version of the story and then tells the same tale in reverse.

Lockwood’s visions suggest that these names and their attached identities are floating free, ready to be claimed or disregarded at will. Indeed, names and identities within Wuthering Heights appear interchangeable. The novel keeps swapping the characters and their names around in order to imagine them in new combinations. In the process, the distinctions between the generations and their attached symbolism start to dissolve.

Circling the story

The pattern of names also suggest that Wuthering Heights is a cyclical tale rather than a linear one. The repetitions introduce all sorts of complications into how we read the two halves of the narrative in relation to each other. From one perspective, the circular structure prevents us from assuming that Wuthering Heights is a tale of doomed passion being eventually superseded and replaced by mature love. From another, the first generation can be interpreted as triumphantly returning. We start with a Catherine Earnshaw and end up looping back to a Catherine Earnshaw.

Of course, Wuthering Heights is too sophisticated to give us an either/or answer as to whether passion or companionship is preferable. On closer inspection, Catherine and Hareton possess many of the same qualities as their forebears but in less extreme and more domesticated forms. In the final chapter, the pair is described as reading together in a recently replanted garden, a detail that suggests the violence and chaos of the Heights has been tamed. They symbolise a harmonious synthesis of the many oppositions – especially nature/culture and passion/companionship – that abound in the novel. In this hybrid setting, the younger Catherine’s taking of her mother’s maiden name creates the impression of a simultaneous return and renewal.

The novel’s recurring names and its overall design suggests other possibilities. In particular, that Brontë was more interested in weaving a complex narrative than answering the very questions raised by her own novel. In so doing, she crafted a literary and philosophical puzzle that continues to ignite the imaginations of many authors, filmmakers and artists to this day.