Not every archaeological discovery is made by opening the tomb of a long dead king. Indeed, some important finds seem inconsequential at first. Such as ostrich feathers stained with ochre, a leather bag containing emperor moth cocoons and a strange vessel made from the cranium of an African wild dog I unearthed from a sterile layer at Falls Rock Shelter. The site lies just below the summit of the remote Dâures (or Brandberg) massif in the desert region of western Namibia.

Perplexed, I consigned these finds, first buried 4,500 years ago, to a box beneath my desk. They lay there for another 40 years until, in a flash of realisation, I saw that the emperor moth cocoons were pierced to be strung as rattles worn around the ankles of a shaman in ritual dance.

As set out in my new book Namib – the archaeology of an African desert, these delicate, brittle things were to provide a new understanding of shamanic ritual performance as depicted in the rock art in Namibia and elsewhere in southern Africa.

The role of the shaman as a ritual specialist and healer among southern African hunter-gatherer societies is known mainly from rock art depictions. Until now, no archaeological evidence of shamanic ritual paraphernalia had been discovered in southern Africa.

A new era

When I excavated the site, rock art studies had just entered an exciting new era. They left behind antiquarian musings for a theoretically rigorous approach. This was informed by modern anthropology and the great trove of late 1800s historical ethnographic material on the inhabitants of the region compiled by the German linguist Wilhelm Bleek.

Read more: South Africa's bandit slaves and the rock art of resistance

Scholars were able to offer detailed and convincing explanations of mysterious rituals in which shamans drew upon supernatural sources of potency to heal, guide and protect their people. Paintings which had seemed inexplicable – some were dismissed as irrational fantasies – yielded their meaning. The spiritual world of southern African hunter-gatherer opened to enquiry.

Many puzzles remained, of course, but some rock paintings offered such depths of insight that one even became known as the Rosetta Stone of rock art studies. The key to deciphering the rock art was the trance dance, a public ritual in which the shaman achieved a state of altered consciousness through rhythmic dancing, accompanied by clapping and singing.

Evidence from the Namib Desert

Southern African scholars argue that rock art and shamanic practice was not hidden: it was open for all to see. An egalitarian hunter-gatherer society had no place for specialist ritual practitioners. Other shamanic traditions are described by scholars of religion as essentially “polyphase”. This means having a phase of occultation, when the shaman is hidden or concealed, followed by his emergence or reappearance.

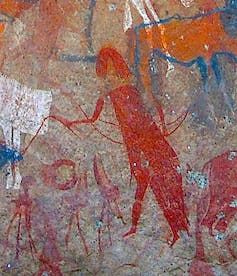

Namib Desert rock art has many hidden sites, including paintings in dark crevices that cannot admit more than one person. These sites were part of a preparatory process which preceded a ritual performance. A striking feature of the rock art is its highly individualised figures, clearly shamans, overwhelmingly male and replete with specialised ritual equipment, including fly whisks, moth cocoon dancing rattles and long animal skin cloaks almost concealing the body. Significantly, these figures are not shown as participating in communal trance dance.

The evidence suggests that shamans in the Namib were individual specialists who travelled from place to place. They prepared themselves for ritual action in places of physical seclusion, rather than during the large communal trance dance events that rock art scholars have insisted were the fundamental social mechanism for trance experience throughout this region.

Enigmatically, no trace of ritual paraphernalia had been found elsewhere in southern Africa. This has led scholars to suggest that there probably were no such items and that the rock art represents concepts such as power and control rather than actual items of material culture.

So, what of the emperor moth dancing rattles? Are they no more than an unusual and accidental find, adding a little texture to our understanding of the rock art? On the contrary, they show that occultation, as an element of performance not previously considered by scholars of the region, is of fundamental importance to an understanding of the art and ritual practice of southern African hunter-gatherers. The rattles expose a critical weakness in conventional explanations.

The emperor moth dancing rattles

Moth cocoons with small pebbles placed inside and strung about the lower limbs, issue a characteristic rustling sound, a rhythmic accompaniment to the ritual dance. Their significance goes much further, for the cocoon represents the stage of occultation when the moth larva is hidden from view. The moth itself is the emergent stage represented by the dancing shaman: once hidden, now apparent.

Paintings of emperor moths are rare but those in the Dâures massif are shown with the wings extended as in the emergent stage. The painted moth represents the shaman with his knee-length animal hide cloak which resembles the wings. The cocoon rattle, the moth and the cloaked shaman thus combine the two essential stages of ritual performance: concealment and reappearance.

Cloaked figures are, of course, not confined to the rock art of the Namib Desert. The fact that they occur over much of southern Africa shows that they refer to a basic trope in this ritual tradition, overlooked until now.

The occultation and emergence of the emperor moth has further ramifications, too. It explains the importance of physical seclusion, such as in the deep rock crevices found in the desert, as sites of ritual preparation from which the shaman emerges to perform his work. It also explains why the cocoons and other ritual items were buried at the site; these are objects imbued with supernatural potency and therefore kept hidden, in a state of latency, lest their powers be misused.

Now we see that these small items are more important than they might at first appear. Indeed, they provide the first integration of southern African rock art and hunter-gatherer ritual practice on the basis of firmly dated archaeological evidence. They alleviate a long-standing and counter-productive separation of rock art studies and the less glamorous field of “dirt” archaeology.

Perhaps the evidence from the Namib is not unique after all; there may well be cocoon rattles elsewhere, and dark crevices with hidden rock art still waiting to be found.

Namib – the archaeology of an African desert was originally published by the University of Namibia Press. It is available from Wits University Press and is also available internationally from Boydell & Brewer.