It comes up, from time to time. Ethics and writing. Two concepts that are chained together in a dysfunctional marriage. How to write, ethically? How to write ethically while remaining true to the aesthetic imperative, the narrative trajectory, a reader’s requirements? And, by the way, what is ethical writing?

In the field of education the answer is straightforward: to write ethically means avoiding plagiarism, and resisting the impulse to make up “facts”.

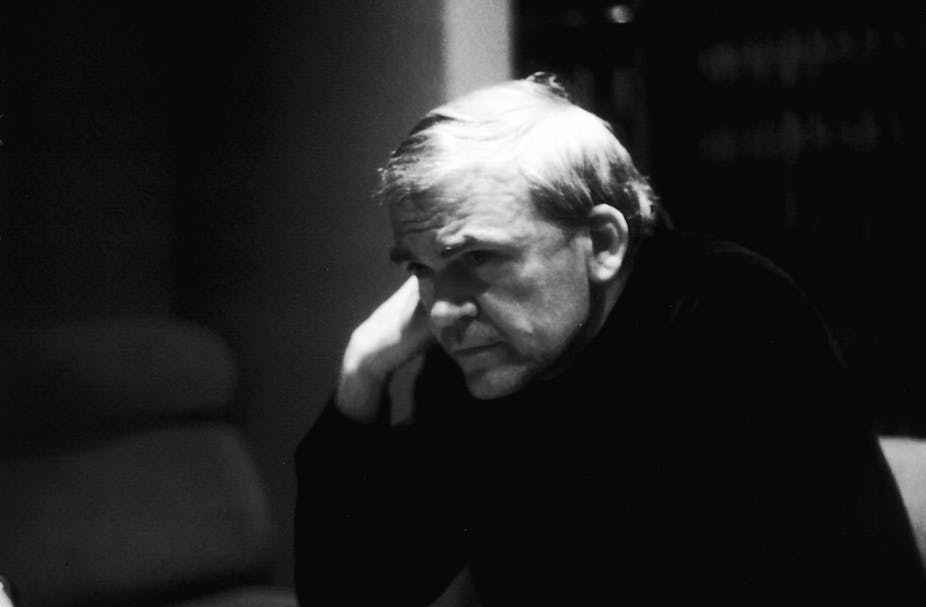

For Milan Kundera, the answer is straightforward.

A novel that does not discover a hitherto unknown segment of existence is immoral. Knowledge is the novel’s only morality.

For Oscar Wilde, the answer is straightforward. “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book”, he writes, in the preface to his The Picture of Dorian Grey.

Books are well written or badly written. That is all.

These answers don’t help much. Creative writers necessarily avoid plagiarism, but we necessarily make things up. Not all writers feel impelled to contribute knowledge. And, Mr Wilde, what is the actual difference between “well written” and “badly written”?

Good; bad: like “ethics”, these words are what scholars of semiotics call “empty signifiers”. Any word stands in for the object or concept it names. But, except for proper nouns, no word really stands in for anything else; all any of them can do is direct our attention to the thing or concept being named. Empty signifiers are words that point to no concrete object, no agreed meaning; words that “absorb rather than emit meaning”.

To say “good writing” and “ethical writing” is to name concepts that apparently “we all” recognise, but on which “we all” are unlikely to agree. (My “good writing” is your pulp fiction. Et cetera.)

It’s an issue of taste, to some extent; or of contemporary values; or of politics. Which is where we come back to ethics. I won’t try to summarise the vast literature on ethics here. My concern is how we tell stories, and produce images, that contain a certain organic “truth” (that word very deliberately rendered in scare quotes, since it is yet another empty signifier), and that avoid didacticism.

Joan Didion begins her essay Why I Write by describing the art as one of

imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind.

Yes certainly; but continually “imposing oneself upon other people” can leave us looking rather like the monks in Monty Python and the Holy Grail: endlessly chanting the same phrase, endlessly hitting ourselves (and our readers) over the head.

There is no complete answer to the question of ethical writing; but perhaps Michel Foucault comes close in his observation that

ethics is the considered form that freedom takes when it is informed by reflection.

That is, ethical writing is the writing we do when we have consciously reflected on the meanings we are making, or the world we are representing. I may not like a work, and I may not agree with its worldview, but (pace Oscar Wilde) if it was written under the conditions of reflective practice, it is necessarily ethical.

Writers are always making representations: materialising the world and relationships within that world; because words do more than simply name the things for which they stand. Organized into phrases, sentences, paragraphs, whole works, words can construct a context that readers will feel, see, hear, smell.

Words, organized in this way, can bridge the divide between the abstraction of language, and the concreteness of the material world; can make things (seem, and feel) real.

Perhaps this is a way to think about ethical writing: we can use language to make work that addresses the actuality of things, and the lived experience of many people.

The power of narrative and poetic representation is evident in the emotional, visceral, responses people have to works that manage materiality well. Whether it’s laughter or tears or recounting the experience to friends, “good” writing moves us.

The efforts of governments to censor representational works also points to the power of such works. The attempt by the Australian government, in 2001, to ensure that “there were no personalising or humanising images” of refugees is one such example.

Australian writers and artists have, over the past 15 years, responded to this decree not with silence or abstractions, but with works that personalize and individualise. Writers in detention centres in Australia or the Pacific are also writing poems and stories and recording impressions that personalize, individualise, humanize those communities.

Some such works may be agitprop, others naïve or didactic. But for me, many are ethical in the terms defined by Wilde and Kundera: they are “well written”, using elegant sentences, fresh approaches; and they expose “a hitherto unknown segment of existence”.