One year after the outbreak of civil war in Ethiopia the spectre of regime change looms over Africa’s second most populous nation. The tides of the military conflict pitting Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and his allies against the rebel Tigray Defence Forces and Oromo Liberation Army changed after a government offensive failed to push back their enemies in October. Instead the insurgents made important territorial gains over the past weeks, vowing to take the capital Addis Ababa.

In response, the government called on civilians to join the war effort against the ‘terrorists’. It also declared a nation-wide state of emergency.

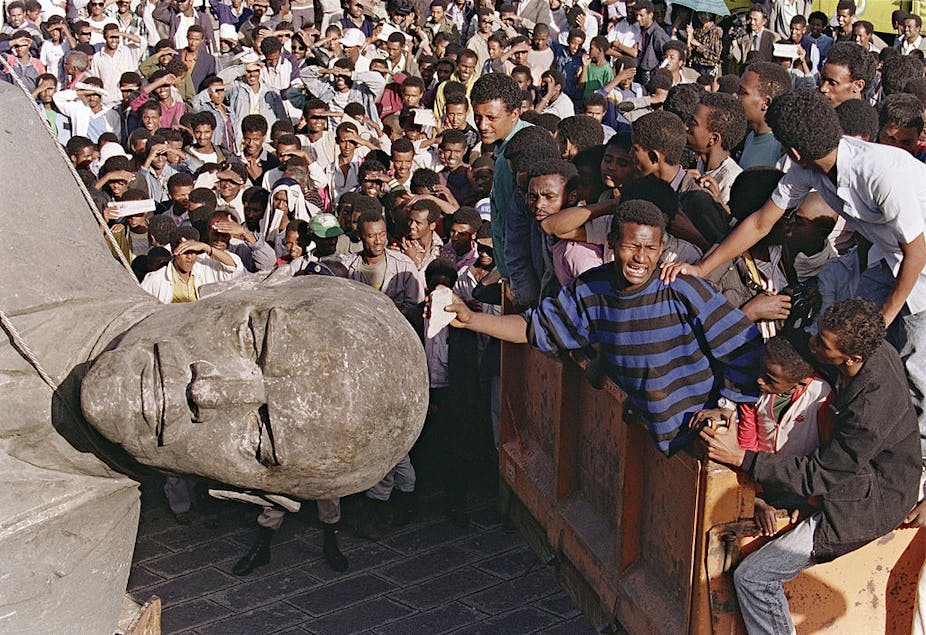

The military outcome of the conflict remains uncertain. Nevertheless, the threat to Abiy’s elected government is reminiscent of the downfall of the Derg dictatorship in May 1991. Led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, the socialist military regime ruled Ethiopia for 17 years after the 1974 revolution that deposed emperor Haile Selassie. It gained a reputation as one of Africa’s most repressive Cold War governments.

Supporters of Abiy, including many residents in Addis Ababa, fear a victory by Tigrayan and Oromo fighters. This could lead to a resurrection of the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front, which ruled the country for 27 years. This coalition of ethno-national parties, led by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, ruled with an iron fist until Abiy’s unexpected rise to power in April 2018.

Those in favour of the rebels argue that Abiy’s nationalist politics seek to undo the autonomy and political rights of the country’s various ethno-linguistic groups.

At a superficial level the conflict is between, on the one hand, a pan-Ethiopianist political centre advocating for a more unitarian state and, on the other, ethno-nationalist forces fighting for a federal order. This follows a familiar fault line in modern Ethiopian politics.

But, based on my long-term research on local and national politics in Ethiopia, this is where historical parallels between the current and past conflicts in Ethiopia end. A 1991 type of regime change at national level is unlikely, even if the Tigray Defence Forces and Oromo Liberation Army – which recently established the nine-member United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces – were to prevail militarily.

Prevailing political attitudes, security actors, alliances and geopolitics differ starkly from the final days of the hated Derg military regime. Five reasons in particular explain why 2021 is not 1991.

1. Abiy’s leadership is not deeply unpopular

When Tigray People’s Liberation Front forces entered Addis Ababa in May 1991 after 16 years of guerrilla warfare against one of Africa’s strongest armies, the Derg government was deeply unpopular. The same cannot be said about Abiy’s Prosperity Party. The party enjoys considerable support in Addis Ababa and parts of Amhara and Oromia regions. It is popular in major cities across the country and among parts of the Ethiopian diaspora.

The Tigrayan-led forces were welcomed as liberators three decades ago. But that’s unlikely to happen today. Many Ethiopians remember the pre-Abiy regime for its uncompromising authoritarian rule and broken promises to democratise Ethiopia.

Few believe that a reincarnated Tigray-led transitional government will solve the country’s deep seated political problems, in particular inter-ethnic animosities.

2. Proliferation of inter-communal conflicts

Today’s security environment is very different. The federal army has been considerably weakened after a year of war. The removal of senior Tigrayan commanders from the Ethiopian National Defence Forces after Abiy came to power is another factor. These commanders are now on the Tigray Defence Forces’ side.

The Ethiopian army’s ability to lead and coordinate operations has diminished while security forces operating under the command of regional states have strengthened. These ‘special forces’ of Amhara, Oromia, Afar and other regions – not the army – have shouldered much of the recent fighting against the Tigrayan and Oromo rebels.

In Amhara region in particular, thousands of local nationalists have joined the war against Tigrayan forces to reverse their gains. A proliferation of inter-communal conflicts across the country and a militarisation of Ethiopian society mean that, militarily speaking, neither the rebels nor the government are the only game in town.

3. Fragile alliances

The political alliances underpinning both Abiy’s government and the rebel coalition are fragile at best. The Amhara and Oromo wings of the ruling Prosperity Party are held together by their joint animosity towards Tigray. Inter-ethnic conflicts between Amhara and Oromo communities in both regional states has been a source of tension within the ruling party. Amhara nationalists feel increasingly let down by Abiy’s government and are likely to continue fighting against Tigrayans even in the unlikely event of a peace deal.

On the rebel side cooperation between Tigray and Oromo forces is based on an opportunistic calculus as well. Oromo nationalists were sidelined from political power during the early years of the previous regime, when the Tigray People’s Liberation Front was in power.

4. The Eritrean factor

When Tigray People’s Liberation Front forces entered the capital three decades ago, they were backed by the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front. This paved the way for the secession of Eritrea. Between 1998-2000 however, Ethiopia and Eritrea went to war driving a wedge between the Tigrayan and Eritrean leadership.

Abiy’s peace agreement with Eritrean president Isaias Afwerki, signed in 2018, turned out to be a military pact against their common enemy – the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. Eritrean defence forces invaded Tigray in the early days of the war, playing a crucial role in the government’s early battle wins.

What’s more, future relations between Tigray and Eritrea have the potential for long-term destabilisation in the northern parts of Ethiopia.

5. The Tigray question

Finally, Tigrayan elites are themselves divided over strategy. The options are between further decentralisation of the country or secession of Tigray in line with article 39 of the Ethiopian constitution. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front has long argued that self-determination within Ethiopia was in the best interest of Tigrayans. But the war and humanitarian crisis in Tigray have pushed many Tigrayans to rally behind calls for secession.

For the time being the main objective is to defeat Abiy’s government. The other is to liberate what they consider as Amhara-occupied territories in western Tigray, and to establish a national transitional government. But Tigray’s political future remains very much in the balance.