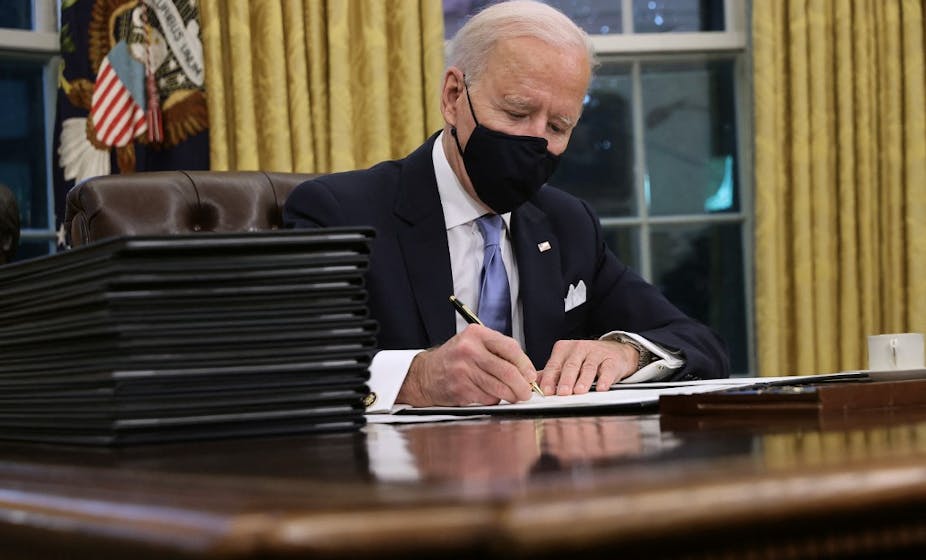

Before his election, Joe Biden had launched the idea of an “alliance of democracies”, previously put forward by some of his advisers, notably Antony Blinken, the future American secretary of state.

This idea aroused some scepticism in the United States as well as in other countries. In Europe, there’s a concern that it could increase divisions and limit room for discussions with authoritarian regimes; some even detect a whiff of the Cold War. This collides with other sensitive debates, not the least of which is that on Europe’s “strategic autonomy” and the raison d’être of the Atlantic alliance.

Why is such an alliance of democracies and for democracy necessary? How to change our foreign policy paradigms? What goals should it pursue? How might it proceed?

The division of the world

In an increasingly visible way, the main division of the world is becoming that between dictatorships and liberal democracies, with certainly points of nuance and degrees, but also uncertain zones which can prefigure tipping points. The question of the fall of democracies, even those that seemed the most established, is far from being rhetorical or to be relegated to the history of dark times. The Trump episode and the January 6 attack on the US Capitol have shown this. Orbán’s Hungary offers another example. France is not immune to such a virus, and a victory of the far right isn’t an impossible scenario.

Internationally, a kind of “alliance of dictatorships”, often referred to as criminal regimes, is quietly forming. We see it in action in the UN as well as in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. This is seen in the ad hoc solidarity that is being established against democracies, beyond the differences that dictatorships may have with each other. After the 16 Russian and often Chinese vetoes on Syria, we have seen the same alliance take shape on Burma. It is asserted on the ideological level, with dictatorships expressing a shared hostility toward the rule of law, especially international law, human rights, political and social liberalism and – crowning the edifice – the very concept of truth.

The idea behind the establishment of an alliance for democracy is not only to stop their domination of the international scene, but also to detach certain countries from their grip. It is a matter of democracies regaining control after a period in which dictatorships have been able, because of our abstention, to dictate the international agenda.

A paradigm shift for foreign policy

If we want to be serious about defending democracy, we need to change five paradigms of our foreign action, which are dominant today.

First, we must put rights back at the center. Not only does the violation of rights, from the assassination of Russian dissidents to the harsh repression in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, particularly by the great powers, often foreshadow external aggression, but the silence that surrounds it, in the name of a supposed Realpolitik, consecrates the weakness of democracies in the eyes of dictators.

Secondly, we must say and name things. When China commits crimes against humanity, or even, in the words of Mike Pompeo and then Antony Blinken, genocide in Xinjiang against the Uyghurs, we must call them such. The same is true when Russia commits war crimes in Syria, Ukraine and Georgia. Not to allow this to happen is to contribute to the revival of international law, which the dictatorships want to destroy.

Thirdly, we must consider the possible pitfalls of multilateralism. Everyone can see it as an asset, but dictatorships also play on it to assert their claims to diversity – the authorization to have a repressive system – and to present themselves as equally legitimate members of a system based on this law that they intend to undermine. In a multilateral system, while theoretical equality is the rule, some are more equal than others. In this sense, the attempts to put the P5 back in the center of the game lead to giving the two dictatorships that are part of it, a preponderant weight.

For the moment, this implies not relying too much on the UN system on security issues. The positions of the Russian and Chinese regimes make it a concrete obstacle in the resolution of the most serious conflicts. A coherent alliance of democracies cannot expect the UN to authorize its involvement.

Finally, the defense of democracy rules out the classic salami-slicing of subjects in which the propaganda of the democracies instills itself. In particular, to think that we can link trade and security, or even the fight against climate change and human rights, is an illusion when we prove ourselves incapable of seriously countering dictatorships. The recent example of Germany, claiming to want to work with Russia on environmental issues – in addition to Nord Stream 2 – shows the dangers of cooperation that leads to inaction.

The order of the challenges

The Alliance for Democracy is certainly not intended in most cases to eliminate dictatorships by military force. Who would consider attacking Russia or China? But we must curb the contagion, that is to say the number of regimes that risk falling under the control of the most powerful authoritarian regimes. The defense of democracy requires the rejection of zones of influence in the world, a theme that both Beijing and Moscow want to promote. Dictatorships aim to hinder the exit of peoples toward democracy, to prevent the creation of new alliances with liberal regimes and, when an area cannot be controlled, to maintain it in a state of relative chaos, since this constitutes a threat to the West. Iran, which has its own objectives, thus de facto plays the role of Russia’s deputy through destabilization in the Middle East.

Secondly, it is necessary to take back the countries that have tipped, or are tempted to do so, toward dangerous alliances. Both China and Russia, and to some extent also Turkey, itself the object of pressure from the first two, are trying to draw certain countries into their orbit through diplomatic manoeuvres or invasive investments. This is the case of certain Balkan countries, first of all Serbia, Hungary, but also several countries in the Gulf and in Africa. The success of our diplomacy will be measured by our ability to tie them down.

The space for action

An alliance of democracies makes little sense without a common plan of action. Even if direct confrontation is ruled out, they are not without means.

The first, albeit symbolic, remains the clear affirmation of our principles, from international law, particularly humanitarian law, to the refusal of zones of influence and the revision of borders by force. It is justified by the ideological struggle of the other side to bring them down in practice, in law and in legitimacy. It certainly presupposes a domestic blamelessness. We often hear the reproach, referring to the George W. Bush period: “Let’s not oppose the camp of good to the camp of evil!” It is true that the “good side”, i.e., the West, has committed many crimes, but it has the ability to acknowledge this; its actions can be freely debated, and its perpetrators can be brought to justice. This is not the case in dictatorships where free voices are silenced, sometimes even by assassination. Of course, democracies have traditional allies who may have committed crimes – Yemen comes to mind. But if we value our principles, we can and must speak the truth to them.

The second way we can act is to support our allies, whether they are in Ukraine, Taiwan or Georgia. We must re-establish a credible posture of deterrence. The propagandists of the revisionist regimes warn: “You are in danger of getting us into a third world war.” We have heard this warning too much and given it too much credence, which explains our past inaction.

The third way is to support democracy. While we cannot push for regime change, we must support democratic forces that can engage in it – this applies to the Belarusian, Russian and Chinese opposition. Let us be insensitive to the propaganda of regimes that accuse us of supporting “color revolutions”. We do not create this opposition, but we can help ones that in the name of our values and the freedom of peoples.

Finally, we need a common plan to end our tolerance of the actions of dictatorships on our soil. The fight against corruption in circles close to them will be a decisive step. However, we continue to turn a blind eye to the way in which they can continue to dispense tainted funds on our soil, including using them to gain support at home. We need to cease minimizing these risks, do more to expose and sanction such activities, and harmonize the legal framework from the top down.

The aim of the alliance for democracy is to unite us in an ideological struggle, but one that has a practical dimension on which there can be no distance between our American allies, the free countries of Europe and the democracies of Asia and Oceania. The power we want Europe to acquire cannot be a neutral one. It must both acknowledge the division of the world that the dictatorships are trying to impose on us and actively work to prevent it. Even more than the United States, Europe has an interest in leading this fight.