Channel – the UK government’s “deradicalisation” programme – is growing. More people are being referred for support, including a significant number of under 18-year-olds. Four out of five of these referrals are dropped.

So why are so many people being referred apparently unnecessarily, and what happens to those who do go on to receive support?

Channel operates in the “pre-crime” space. Its aim is to prevent people becoming drawn into terrorism by providing tailored support programmes to those deemed at risk. Anyone – including parents – can refer someone. Public sector employees including teachers and social workers are now statutorily obliged to intervene if they believe an individual is “at risk of radicalisation”.

Identifying people at risk is not easy. Academic and government research largely agree there is no “terrorist profile”. Even Channel’s own guidance states: “there is no single way of identifying who is likely to be vulnerable”.

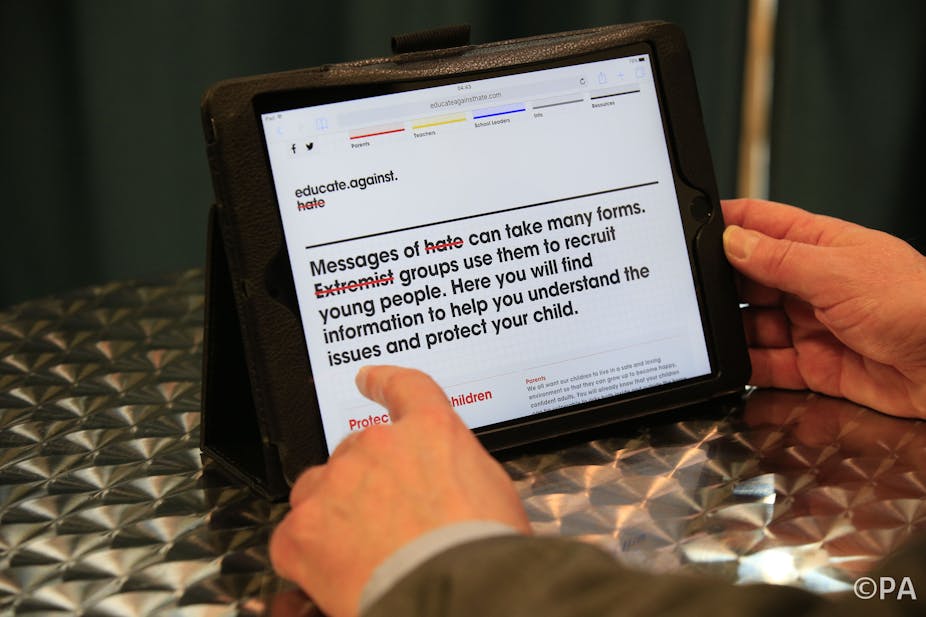

Nevertheless, Educate Against Hate, a new website set up by the government to provide information on extremism, sets out a series of warning signs. These include argumentativeness, changes in clothing, spending excessive time online and secretiveness.

Such measures are easy to criticise; after all, many of them are part of normal adolescent development. As a result, critics highlight the risk of criminalising normal behaviour and threatens to alienate Muslim communities.

Such criticism shouldn’t overlook the experiences of teachers in dealing with safeguarding issues – and the increasing examples of innovative teaching practices addressing extremism.

That is not to say that potential problems should be ignored. There are legitimate concerns that referral decisions might be influenced by fears of being held responsible if something goes wrong, rather than on the basis of evidence and thoughtful deliberation.

With this, comes the risk of shutting down debate in the classroom and stigmatising young Muslims, which some have argued could be counter-productive.

What happens next

Once a case has been referred, the first stage of assessment determines if there is a genuine cause for concern, ensuring the case is not “malicious or misinformed”. The second stage involves a risk assessment guided by 22 indicators deemed to reflect vulnerability. These range from “spending increasing time in the company of other suspected extremists”, to “condoning or supporting violence or harm towards others” and “being criminally versatile and using criminal networks to support extremist goals”.

Where the Channel police practitioner and local authority believe a person is “a risk” or “at risk”, the case is referred to a multi-agency panel which determines the most appropriate strategy. A range of interventions are available, from anger management sessions to education and careers advice, through to theological and ideological mentoring.

Despite efforts to stress the voluntary, safeguarding nature of the Channel process, more coercive mechanisms are also available to the authorities. If an individual refuses to engage, they may be subject to monitoring and surveillance by the police or security services. They can also have their passport seized if the police believe they are likely to try and travel overseas.

Parental consent is required for under 18s to engage with the Channel programme, but if parents refuse the case can be referred to social services if there is believed to be a risk of “significant harm”. Parental consent also seems to be necessary only at the intervention stage, which critics argue is too far down the line.

Relatively little research has been carried out on the process and outcome of the Channel process, making it difficult to determine how effective the programme is. The aims of interventions are not always clear, and there are no publicly accessible evaluations.

Interventions are not always successful. One man who was directed to Channel after time in prison for a terrorism offence said he was “entirely suspicious … as far as I was concerned it was a trap, an opportunity to spy on me”. Where they are effective, mentors based in the community can play a positive role in helping to reintegrate people back into society.

In my own research on community-based work with those convicted of terrorism offences – another population that can fall under Channel’s remit – mentors typically take a holistic approach. Rather than concentrating solely on questions of faith or ideology, they look at the whole range of issues that might be important to the individual. These might include problems with peer groups or family relationships, social exclusion or political grievances.

As one person interviewed for a study on mentoring around extremism put it:

This isn’t just about quoting lines from a particular holy book or a particular tradition, it’s about understanding the individual you’re faced with, and what that individual may have gone through may be far more complicated than actually a theological argument. … Theology might be just a way of that individual expressing other issues that may have happened in their lives.

Safeguarding the vulnerable

It is not unreasonable for the government to try and prevent people becoming involved in terrorism.

The controversy lies in a lack of transparency over how Channel operates, and the challenge of identifying who might be at risk. Some have argued that it targets young Muslims in the context of wide-ranging legislation which controversially bans “non-violent extremism”.

The statutory duty to report those considered “at risk” and the ongoing conflict in the Middle East both help to explain the increase in referrals. This wider social and political context can lead to a more risk-averse approach to referral decisions. It can also make it harder to have those difficult, challenging conversations so vital in developing young people’s critical and caring thinking.

What we need is a measured, proportionate response to the genuine challenge posed by militant recruiters and the avenues the conflict in Syria provides for young people to engage in what some come to believe is a glorious new caliphate. There is a great deal at stake.