Christmas in Darwin often means one thing: rain. The north is famous for its wet season, which runs from November to April, when the vast majority of the region’s rain falls.

The flora, fauna and people of the north have adapted to the Australian monsoon and now depend on the arrival of the rain for their survival. Living as we do on an arid continent, it is natural to eye this seasonal source of water as an important resource for agriculture and other economic activity.

But the summer monsoon is also notoriously fickle. Last year’s wet season was the driest since 1992, although there is some evidence that this year will be better. So what drives this important weather phenomenon, and how might it change in the future?

What is the Australian monsoon?

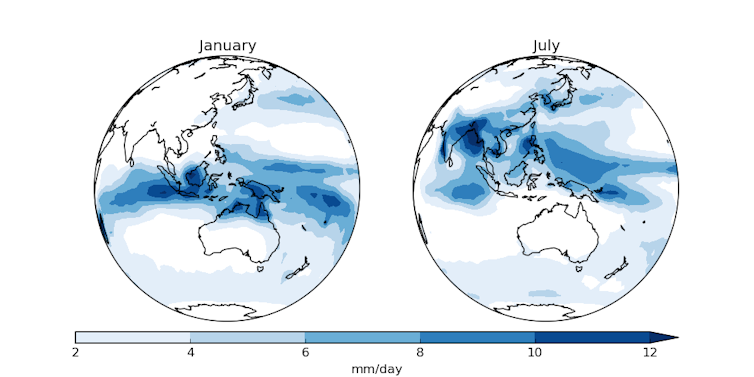

The Australian monsoon actually alternates between two seasonal phases linked to wind direction. In the winter phase, easterly trade winds bring dry conditions. In the summer, westerly winds bring sustained rainy conditions. In fact, the word “monsoon” comes from the Arabic word for season.

As the summer approaches, the sun heats the Australian land area faster than the surrounding ocean in much the same way as the pavement next to an outdoor swimming pool is heated faster than the pool water.

This difference in heating also produces a difference in pressure, which is lower over the land than the ocean. As a result, warm, moist air from the tropical ocean is drawn towards the lower pressure over the hot and dry north of Australia. It is this increase in humidity in the month or so prior to the sustained rains (known also as the “build-up”) that makes life so uncomfortable for many, driving some people “troppo”.

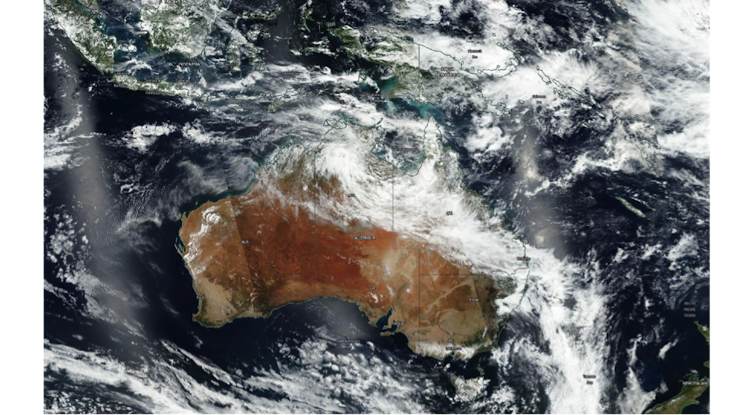

With increasing humidity, conditions become progressively better for the development of deep clouds and storms.

Eventually, sustained rain, low pressure (the “monsoon trough”) and deep westerly winds become established over land. This transition can be relatively abrupt, and at Darwin usually occurs around Christmas Day, although there is a great deal of variability from year to year.

Why so variable?

Unsurprisingly, El Niño (and its counterpart, La Niña) is partly responsible for the monsoon’s variability.

In El Niño years, the summer monsoon tends to be drier than average, and last year was no exception.

However, El Niño (or La Niña) usually influences only the early part of the season. Once the summer monsoon becomes established, the relationship with El Niño (or La Niña) becomes weaker.

The tropical oceans just to the north of Australia also play a role in the variability. Warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures and greater evaporation have contributed to an early onset of summer monsoon this year by increasing the moisture early in the season.

Rainfall in the Australian summer monsoon occurs in a series of bursts, each of which may last for a few days or weeks. The relatively dry periods between the bursts are referred to as breaks, which can last for lengths similar to bursts. The total amount of rain that falls in a season depends on the intensity of the bursts, their number and their duration.

The science of bursts

One ingredient in rainfall bursts is the envelope of deep clouds known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO). This eastward-moving atmospheric wave organises deep clouds in the tropics and is often linked to widespread rainfall as it passes over the north of Australia.

This wave has a period (the length of time between rises and falls) of 30 to 60 days, and is closely monitored by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

Recent research has shown that a second important ingredient is the mid-latitude troughs (zones of low pressure) that periodically move towards the equator into the tropics. Such troughs rapidly increase the moisture in the monsoon trough and are associated with two-thirds of all bursts.

These influences also work together to produce rainfall bursts in the Australian monsoon.

What about climate change?

The jury is still out on this one, although there are hints as to what might be ahead.

State-of-the-art climate models furiously disagree on whether there will be more or less rainfall and how much more or less in the north of Australia. Although there are reasons to believe that the monsoon regions may become wetter in a warmer world, monsoons pose a challenge for climate models as they depend very strongly on the relationship between the atmosphere, the land and the ocean.

However, recent advances in understanding the role of the mid-latitudes in producing rainfall bursts may help us to untangle some of the uncertainties in the models.

The continuing research into understanding and predicting the Australian summer monsoon will help in planning for the future in this important region.