Zines are small-circulation, self-published magazines.

Their emergence can be traced back to fanzine, a term used by science-fiction fans from the 1940s to set their amateur publications about popular cultural forms apart from the official fan magazines published by media organisations to promote their products.

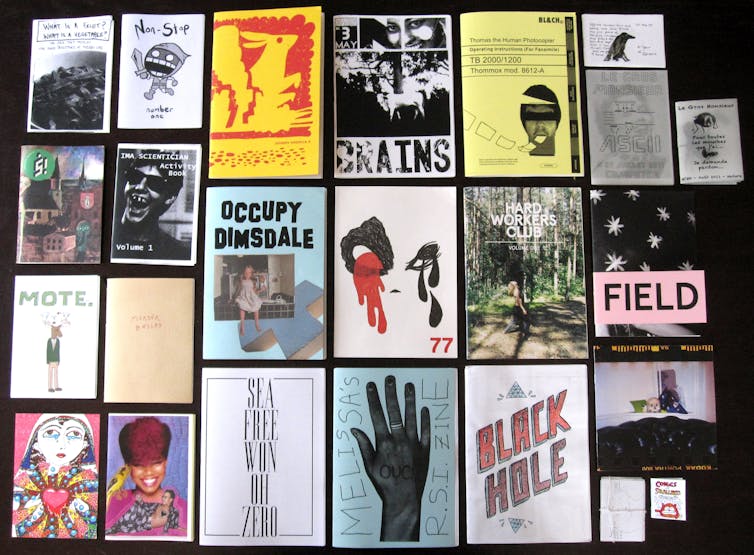

The further contraction to “zine” indicates the expanding range of topics addressed by self-publishers, from other fan-based topics, including music and soccer, to include an infinite range of interests from the political to the creative and the personal.

The genealogy of zine also reveals the extent to which questions about relations of cultural production occupy the creators of zines. For many zine publishers, producing a zine involves an explicit rejection of institutional values: the zine is a medium thought to allow for authentic expression unfettered by the pursuit of profit, traditional news values, dominant aesthetic standards, even the rules of spelling and punctuation.

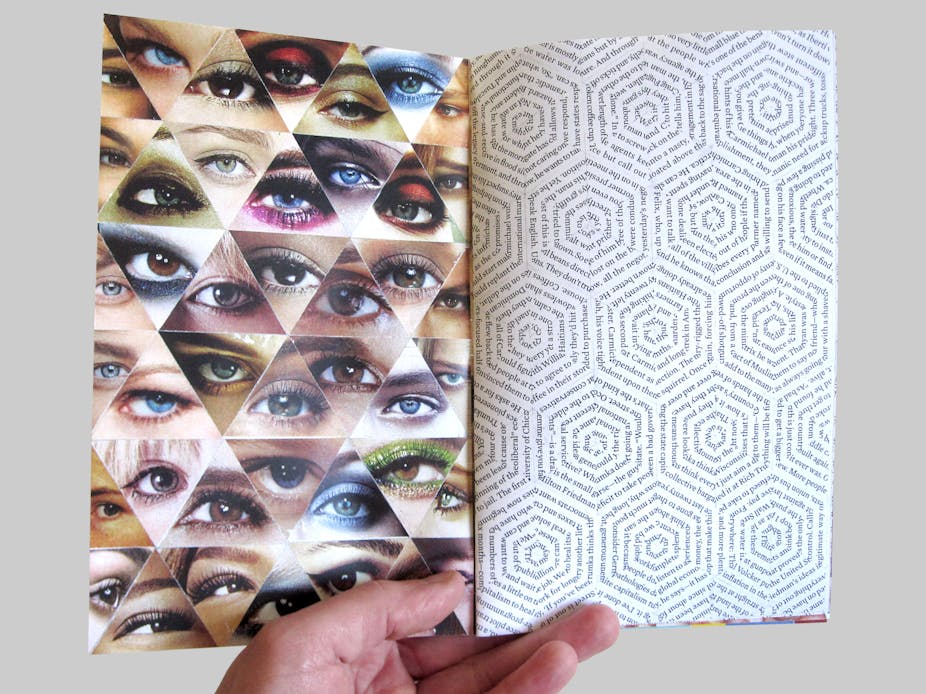

Certainly, the content of zines can be as idiosyncratic as individual publishers choose, and as a form it accommodates modes of expression not necessarily tolerated in other media, whether due to issues of censorship, copyright, or editorial values and standards.

Zines offer a way for their publishers to participate in cultural criticism and production, to resist becoming a dupe to mass media corporations, by adopting the punk-inflected diy imperative of making-do (as distinct from the DIY of home improvement).

The diy ethos was effectively illustrated in Sideburns, a late 1970s fanzine, via an illustration of three chords marked on a series of roughly drawn guitar frets with the captions:

This is a chord. This is another. This is a third. Now form a band.

The zine equivalent might be:

This is a pen. Here’s some paper. This is glue. This is a pair of scissors. Now make a zine.

To maintain their independence, zine publishers have found value in the aesthetics of necessity. While early zines were generally mimeographed (creating duplicates from a stenci), and contemporary zines are photocopied or cheaply printed, the costs of production are usually borne by their producers and are rarely recouped through sales. In many cases, zine publishers offset the costs of production by utilising resources close at hand – often stationery supplies and office equipment available to them in their places of education and work.

The counter-institutional disposition of the zine publisher’s practice, along with the cut-and-paste aesthetic of zines, has seen some attribute a revolutionary history to the form, drawing parallels with the actions and publications of pamphleteers and artists, including American political revolutionaries, Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin; the Soviet-era samizdat writers; Dada and Surrealist artists; and the Situationists of Paris, France.

In each case, an aspect of the earlier publications is found in the contemporary ones, without adequately accounting for extant political and material conditions. The hand-to-hand circulation of covertly-copied works by Soviet-era samizdat writers is recognised in the hand-to-hand distribution of zine publications between their creators, without acknowledging the different likely personal consequences of the former action compared to swapping publications at a zine fair or through the mail.

The author Greil Marcus asserts that “the question of ancestry in culture is spurious”, suggesting that efforts to attribute a genealogy to contemporary cultural artefacts is, rather, a search for legitimacy, where cultural practitioners look for “familiars” from the past, accomplices from history, to substantiate their practices in view of the scepticism that often meets novelty.

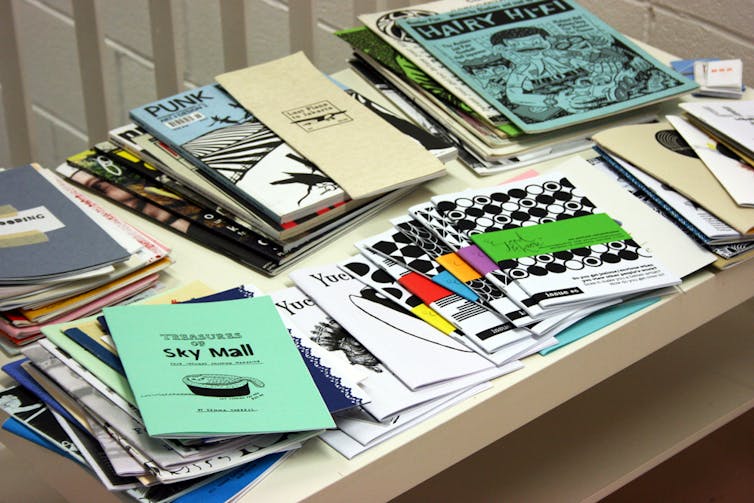

Legitimacy, or at least a broad acknowledgement of the value of the zine form, has largely been realised in Australia since the turn of the millennium. Zine publishers have produced anthologies (such as The New Pollution, Milk Bar) and organised festivals (e.g., NYWF), symposiums (such as ZICS), exhibitions (e.g., Cut ‘n’ Paste: The Great Travelling Zine Show), and exchange fairs (such as Sticky Institute) with the intent of promoting the zine form and encouraging others to create their own publications.

This process of consecration has not always been straightforward. Some zine publishers have regarded these developments with suspicion, criticising the government-funded projects such as The New Pollution on the grounds of their complicity with institutional power, but also self-funded projects, such as Milk Bar, which urged zine publishers to attend to the standards of their publications – to effectively learn a few more chords – which might reduce the accessibility of zine production.

The support for zines by government organisations in Australia has sought to recognise the zine as a form endogenous to young and emerging writers and artists, rather than one imposed by the established arts industry. The Australia Council’s Young People and the Arts Policy formalised principles whereby young people’s existing cultural practices, such as zines, were “acknowledged for their inherent qualities, valued for diversity and innovation”, and recognised for their contribution to Australian culture as a whole.

Similar principles are evident in the policies of state libraries and the National Library of Australia, most of which collect zines as part of their commitment to Australian materials.

While zine publishers such as Tom Cho (Sweet Valley Zine) and Vanessa Berry (Psychobabble, Laughter and the Sound of Teacups, I am a Camera) have subsequently had books, drawing on their zines, published (Cho: Look Who’s Morphing 2009; Berry: Ninety9 2013), or pursued other careers in writing and the arts, including journalism, publishing, design, and academia, the zine continues to flourish as a distinct cultural form.

Alongside self-published digital media, such as blogs, the material qualities and possibilities of the zine, including collage and détournement, prevail. While groups such as the Paper Cuts Collective in Brisbane and the Sticky Institute in Melbourne maintain websites to review zines, they complement an active culture of exchange through mail distribution services, zine fairs and symposia.