The argument has dragged on long enough about who should take the credit for bringing South Africa’s apartheid regime to an end. Of course, some will immediately respond by saying that apartheid has not yet been defeated – it still lives on in innumerable ways. But at least the regime that promulgated the legislation and promoted the ideology has been defeated, whatever remnants remain.

So who, in fact, brought that regime to its knees? There is probably no single, or simple, answer. But one of the groups that certainly played a role was the faith community. Christian leaders like Beyers Naudé, Desmond Tutu and Allan Boesak, played a very significant role in fighting apartheid.

The flip side, though, is that some churches actively supported apartheid. Others, meanwhile, remained silent when they should have spoken out.

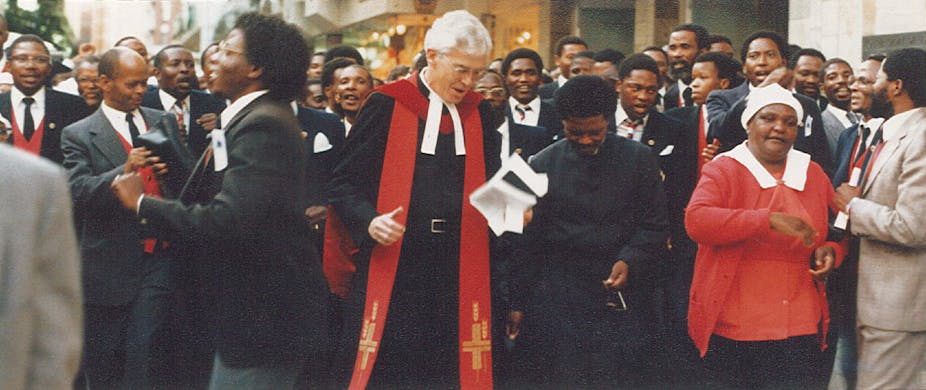

Still, the struggle of some churches – leaders and congregants – against apartheid was both profoundly non-racial and ecumenical. While black voices were predominant, white voices of protest and resistance could also be heard and observed. And while a large number were Methodists, as was Nelson Mandela himself, nobody involved in the church struggle was bothered about denominational affiliation or loyalty.

This, I suggest, is the framework within which to read Peter Storey’s very readable, absorbing, and at times, as the title suggests, provocative book, I Beg to Differ: Ministry Amidst Teargas. Storey, who eventually became the Presiding Bishop of the Methodist Church as well as president of the South African Council of Churches, was one of the white church leaders who played a very important role in the church struggle against apartheid.

Convictions

Who was Storey, what shaped his convictions, and what role did he play, are naturally questions we might ask. And we should ask them, not only out of interest, but in order to understand better how Christian moral and political convictions are nurtured. How did a young white South African brought up under apartheid, educated in a segregated school (all were), and an officer in the South African navy, become a leading opponent of the system?

Also, how did he maintain his faith and hope through many a crisis and challenge, often caught between different factions, and sometimes sidelined. How did he learn to say:

I beg to differ!

An autobiography often resembles an iceberg. We are introduced to what is on the surface, but we don’t always get to see what is beneath. Storey’s narrative certainly presents a public face: the face of a leader, a man of Christian conviction, compassion and commitment. He also takes his reader below that persona to his early upbringing as a son of the manse (his father was also a minister), and later as the devoted husband of Elizabeth – a remarkable person in her own right, and to whom his book is dedicated – and the father of four sons, some of whom followed him into the ministry.

Storey also writes about his personal struggles which are inevitably part of the life of a leader committed to truth. We also discover his interest in making furniture and his interest in sailing. I can speak about this from personal experience. Under his captaincy and along with Elizabeth, my wife and I successfully sailed off the Cape Town coast on a stormy afternoon in what seemed to us a rather small craft for such an occasion. But that is a parable of Storey’s leadership, steering a sometimes threatened ark through choppy seas, and doing so with a firm hand on the rudder.

Back to his public face, which perhaps first came to prominence when he became a student leader at Rhodes University, gaining a little notoriety in the process. Then as minister of the Methodist church in Cape Town’s District Six, where he was in the forefront of opposition to the shameful forced removals by the apartheid regime that reduced a vibrant community to a vacant, ghostly plot of land.

Next as a minister in Johannesburg, first in Braamfontein and then at the Central Methodist Mission in the heart of the city. Storey left a large imprint in all these places and contexts.

He spent some of his retirement years as a professor in the US teaching many an aspiring minister. On his return to South Africa he played a leading role in establishing the Seth Mokitimi Methodist Seminary in Pietermaritzburg.

There is so much more that could be said about Storey’s life and witness, from his brave participation in many a protest march, to his courageous standing up for the truth during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission process.

Not all will necessarily agree with him on all he said. I had a few quibbles here and there, but Storey always allowed others to differ just as he begged to do so himself. That is, after all, at the heart if democracy. So anyone interested in the role of the church not just in the struggle against apartheid, but also in the struggle to build a transformed democratic society, should take up this book and read. You won’t be disappointed.

I Beg to Differ: Ministry Amidst Teargas ,Cape Town: Tafelberg._