The UK government has agreed to pay £60,000 to the families of healthcare workers who die from COVID-19 in the line of duty. Is this “death in service” payment generous, or are families being duped?

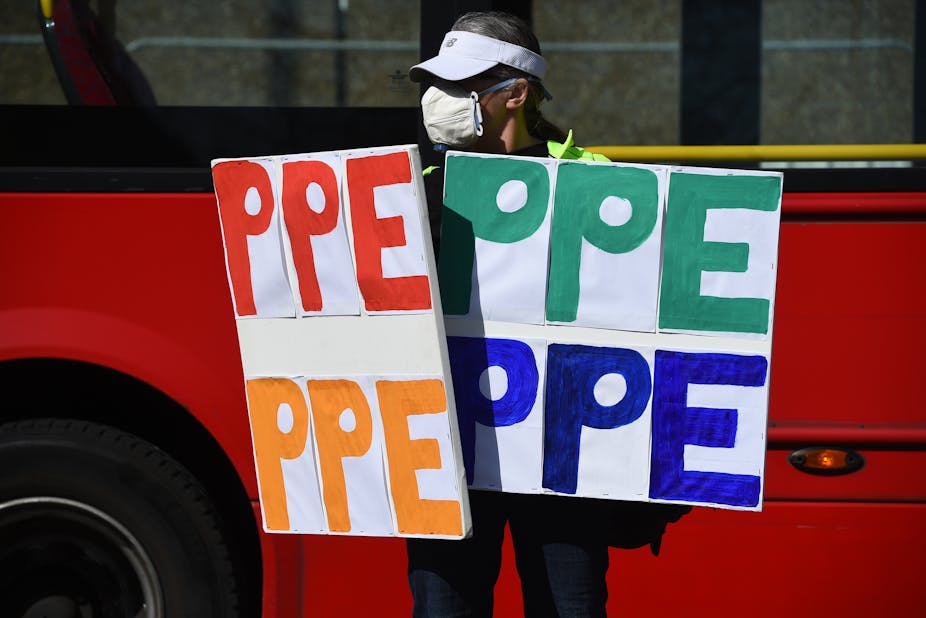

The payment comes after concerns from frontline healthcare workers about the lack of personal protection equipment (PPE) – the gowns, gloves, masks and aprons that should be provided to NHS staff treating patients with coronavirus. But questions have been raised about a failure by the government to provide sufficient protection – and some estimate that the government could end up facing negligence claims of up to £100 million.

More than 100 healthcare workers in the UK have died from COVID-19 while working, leaving their loved ones to claim that the lack of PPE was to blame for their deaths.

What the law says

PPE is regulated via the Personal Protective Equipment at Work regulations 1992, created under the Health And Safety at work Act 1974. They place a duty on employers to provide PPE to all employees who are exposed to a risk to their health and safety while they are at work.

The coronavirus pandemic is clearly a situation in which healthcare workers could expect their employers to provide adequate PPE for their own protection and that of their patients. Additionally, the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002 places further onus on employers to control the spread of the virus among healthcare staff.

Though healthcare providers will be hard pressed in the current pandemic, they remain obliged to assess and minimise the risks to their staff of exposure to biological hazards. The government downgraded its guidance on PPE in March 2020, a decision that some members of an official committee suggested to BBC Panorama was made, in part, because of a lack of PPE.

The government’s offer of a £60,000 payout will not cover the huge emotional losses to families – and for many will not compensate for financial hardships from losing a contributor or breadwinner from the household income. Clearly £60,000 is not enough to cover a lifetime of income lost.

Representatives of healthcare workers cautiously welcomed an offer of financial assistance, but said they would be looking closely at the details. They warned that it should not distract from the need to protect those still working alongside coronavirus patients.

Taking it to the civil courts

Those who have suffered harm due to a lack of PPE could make a claim for damages via civil law, citing negligence on their employer’s part. The Tort of Negligence is a legal wrong that is suffered by someone at the hands of another who fails to take proper care. The remedy is to place the injured party in the position they would have been in had the tort not taken place.

In order for negligence in healthcare to be established, three things have to be proved. First that a duty of care is owed, which seems unproblematic here. Also that the employee can prove that the employer breached this duty – the government has not admitted a breach in duty but has admitted to a shortage in supplies. Finally, that the employee can prove that the harm caused to them was directly because of the breach of the duty owed.

Representatives (usually families) of the healthcare workers who have died can make claims citing negligence and claim for damages on behalf of the deceased. It can be a claim via their estate for personal injuries, and actionable through s.15 of the Trustee Act 1925. This allows the personal representatives of the deceased’s estate to make, accept and settle claims – and any compensation must be distributed according to a will or intestacy provisions.

There is a second course of action by the deceased’s dependants under the Fatal Accidents Act 1976. Their claim would be for the amount for which they were dependent on the deceased. This amount could compensate for the deceased’s loss of earnings. This second action has been held by the courts to be independent of the action by the estate in the case of Reader v Molesworth (2007), which means both claims for negligence and loss of earnings can be pursued simultaneously.

You can imagine that losses claimed under the Fatal Accidents Act will be significantly more than £60,000 for dependants of consultants and senior healthcare professionals.

Entitlement could be more

It is likely that any offers to pay grieving families by the government will be accompanied by a waiver of all outstanding and future claims or actions. These can be in the form of settlement agreements which are worded to settle any current claims, or which resolve all future claims that could be brought against the NHS.

The government will want to have a clean break so that none of these claims can be brought against them and will want to enter into a settlement agreement with those who accept the £60,000. This settlement agreement will usually be a long addendum (ten or so pages is not uncommon) at the end of any agreement document that is signed.

Families of deceased healthcare workers will need to take thorough legal advice before accepting the £60,000, as their claims might be worth considerably more than the sum offered by the government. Legal advice would cover the likelihood of their claim for negligence succeeding and the amount of damages they could expect to win at court. The government will be preparing itself for this and has taken its own legal advice already.