Lee Berger is the 2018 recipient of the Frank Fenner Prize for Life Scientist of the Year, one of the Prime Minister’s Prizes for Science announced on October 17.

Lee’s research identified the cause of mysterious and devastating mass frog extinctions that spread across the world starting in the 1970s: it was a skin fungus.

With her colleague Lee Skerratt, here she describes the work that led to her prize, and what is still to be achieved for frog and wildlife conservation in Australia and across the world.

Combating fungi in frogs – why is this important?

Chytridiomycosis might be the worst disease in history. In a matter of decades, the illness cut a swathe through hundreds of species of frogs, causing mass extinctions as it spread out of Asia into Australia and the Americas.

Our research was the first to identify the cause – a novel chytrid fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis – but finding ways to combat the disease requires a lot more work.

Here in Australia, six species have already been driven extinct, and another seven are on the brink. Fortunately, in Australia we also have the unique expertise and perspective to prevent further losses if we devote adequate resources to the problem.

Read more: Frogs v fungus: time is running out to save seven unique species from disease

The keys to our research success have been a cross-disciplinary approach and a focus on delivering conservation outcomes.

Frog declines had been seen around the world from the late 1970s on, but it wasn’t until 1998 that we identified the chytrid fungus as the cause.

Why had nobody else figured this out before?

Discovering the fungus on the skin of frogs was not rocket science, but rather applying the methods from one discipline to a problem in another. An outbreak investigation approach – using the tools of medicine for frog conservation – allowed us to diagnose the cause of the frog deaths.

The main reason this approach was tried in Australia was the broad knowledge and interest of the late Rick Speare, an extraordinarily eclectic scientist, medical doctor and vet. (Like the prize’s namesake Frank Fenner, he was comfortable using his medical expertise for the environment.)

Rick’s help was sought by Keith McDonald, a chief ranger of Queensland and a herpetologist. Keith was concerned about the health of North Queensland frogs after witnessing major declines in the south.

After looking at the pattern of declines the pair thought they saw the trail of an unknown infectious, waterborne disease. They applied for funds to search for a disease.

The idea that an infectious disease might be responsible for frog declines met resistance because of the belief that a pathogen can never cause extinction, because hosts will evolve resistance. So while Rick and Keith did obtain funding to tackle this urgent global mystery, it was only enough to support a single PhD student.

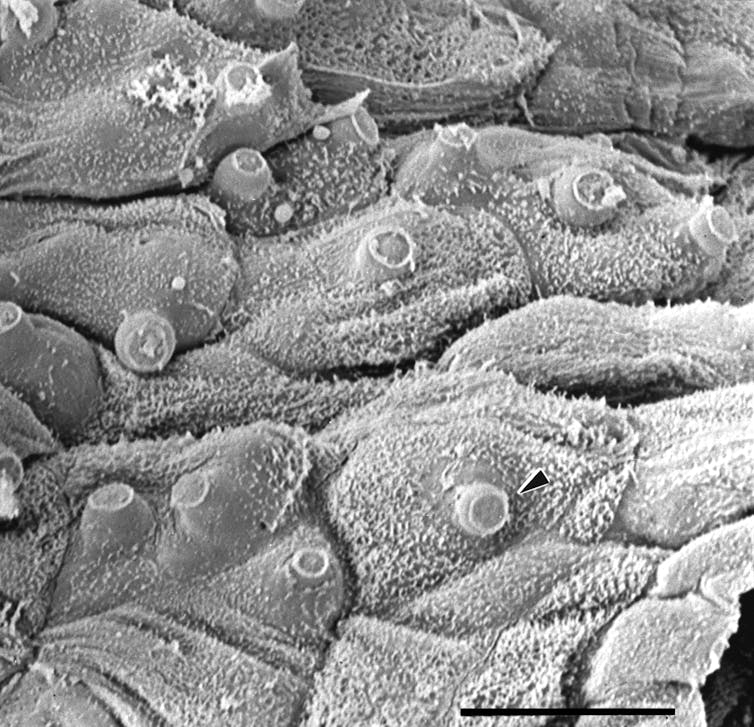

That PhD student was me, Lee Berger. To cut a long story short, my work in pathology and disease transmission experiments in frogs led to our conclusion that a novel and unusual fungus in the frogs’ skin caused a fatal disease and the mass amphibian deaths seen in North Queensland. As this was the first fungus from the phylum Chytridiomycota found to cause disease in a vertebrate, I had to develop many new methods to be able to further study the disease.

So in summary, it was about 20 years after global amphibian declines began that we discovered chytridiomycosis as the cause of the population crashes. It took about another ten years for the disease to be accepted as the prime cause of declines.

After the discovery, what came next?

In subsequent years our research has continued towards the more challenging goal of finding solutions to manage this issue.

Our small multidisciplinary One Health Research Group has tackled diverse questions to reduce the spread and the impact. Questions such as:

- How can we test wild frogs and map Australia for this fungus?

- Where does it occur, and which areas are still at risk of further spread?

- Which disinfectants and medicines kill the fungus?

- How does a skin disease kill frogs?

- Do we need to worry about reservoir hosts?

- Does vaccination work and is immunity evolving?

- What are the current impacts and are some frogs recovering?

Now we are focused on understanding immunity to improve survival rates of the most threatened species of frogs in the wild.

This work has only been possible due to the extraordinary dedication of our students and staff and the collaboration with specialist scientists such as herpetologists, molecular biologists, immunologists, physiologists and others who have lent their expertise.

What does this mean for Australia’s wildlife?

Our research has clearly shown that introduced diseases can have catastrophic impacts for conservation, much like the arrival of feral predators. In fact, disease can cause extinction much more quickly than predators, within months rather than years. The catastrophe of invasive species is a cost of globalisation that will be ongoing unless we respond.

The responsibility for wildlife lies with environment departments, but because health expertise is in other institutes, wildlife health can fall between the cracks.

We argue that continued support for bodies such as Wildlife Health Australia (WHA) is important. We also need a centre of expertise for outbreak investigation and strategic research to develop new tools for wildlife health management.

Biodiversity will miss out unless we support research that promises no direct and fast commercial return but benefits our nation in the longer term. In particular, and most urgently, Australia must save its frogs before it is too late.

Other winners in the 2018 Prime Ministers Science Prizes are:

- Prime Minister’s Prize for Science: Kurt Lambeck

- Prime Minister’s Prize for Innovation: The Finisar team

- Frank Fenner Prize for Life Scientist of the Year: The Finisar team

- Malcolm McIntosh Prize for Physical Scientist of the Year: Jack Clegg

- Prime Minister’s Prize for New Innovators: Geoff Rogers

- Prime Minister’s Prize for Excellence in Science Teaching in Primary Schools: Brett Crawford

- Prime Minister’s Prize for Excellence in Science Teaching in Secondary Schools: Scott Sleap