Launched to coincide with St Andrew’s Day this year on November 30, language app Duolingo’s Gaelic course attracted an impressive 103,000 active learners in its first two weeks – outstripping the number of actual Gaelic speakers in Scotland. The figure also represented more than 18 times the number of adults learning the language in 2018.

Gaelic was spoken in most of Scotland until the 11th century, but a gradual decline in the language means that today, most of the of the country’s Gaelic speakers in Scotland live in the Outer Hebrides (Na h-Eileanan Siar).

It is recognised as a national language of Scotland and initiatives such as the dedicated Gaelic language channel BBC Alba and the growth of Gaelic Medium Education have brought opportunities to those living across Scotland to hear and learn the language.

These initiatives were given a further boost when Gaelic joined a range of endangered languages (including Hawaiian, Navajo and Irish) to be added to the Duolingo platform after a successful social media campaign lobbied for its inclusion.

Of course, not all of the 103,000 people who signed up to Duolingo will be new to Gaelic – and not all will continue with it – but the potential to bring new speakers to the language is considerable. It also raises the question of how this can be used to support the long-term survival of the language, which is considered to be in trouble in Scotland.

Keeping the language alive

As with any endangered language, Gaelic’s health and vitality is often measured by the number of speaker – both as an absolute number and as a percentage of the overall population. The larger the number of speakers and the greater the percentage of the population, the more chance the language will survive and continue.

Languages considered “safe” typically maintain the speaker population at a steady level through the language passing from generation to generation, where children learn it in the home. Languages that are endangered – including Gaelic – often have low levels of generation to generation sharing as a result of caregivers being unable or unwilling to speak the language.

In these situations the language needs to rely on new speakers – individuals who have learned a language outside the home, perhaps at school or as adults, and can use it in their daily lives. Learning a language and being able to speak it is not the same as actively using a language.

The need to increase both the number of speakers of Gaelic and those using it was recognised in the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act of 2005. This aimed to secure the status of Gaelic by making it an official language of Scotland, commanding equal respect with the English language.

As a result, Bòrd na Gàidhlig was established to oversee its promotion through a national plan for Gaelic. It was also set up to support the creation of Gaelic language plans by public bodies, helping them to set out their strategies for promoting the language within the services their organisations provide.

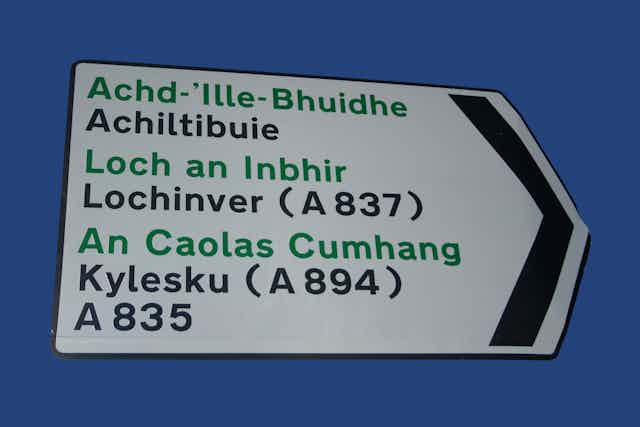

These plans have contributed to the increasing visibility of Gaelic in the public landscape – such as bilingual railway station names and road signs. My own research has shown that, while the inclusion of Gaelic on signs raises the visibility of the language, bilingual signs do not result in greater spoken language use. But it did find a link between individuals hearing Gaelic being used and being willing to use the language themselves in that particular place.

This is not surprising. All Gaelic speakers speak English and it can be difficult to identify Gaelic speakers in a community unless you hear a person use the language themselves. People felt encouraged to use their own Gaelic skills when they heard other people speak the language, even where most of the other conversations were in English.

The focus needs to be not just on creating new Gaelic speakers, but also ensuring that those who have learned the language, or are learning through the likes of Duolingo for example, can hear it spoken in the community, with opportunities to use it themselves.

This is no easy task – less than 2% of the Scottish population can speak Gaelic. But perhaps Bòrd na Gàidhlig’s new programme, Cleachd i (Use it), based on the Welsh Iaith Gwaith initiative, might provide the answer. Speakers are asked to indicate their willingness to speak Gaelic by wearing a small badge or lanyard to encourage conversations in the language. If all those who signed up for the Duolingo Gaelic course got on board, we might start hearing Gaelic being used all across Scotland once more.

The situation for Gaelic is critical – the number of speakers needs to increase. But just as important is the increase in its actual use. Now the real focus should be on ensuring that people are speaking the language in their daily lives. Shops and other community settings should encourage the use of spoken Gaelic. Speakers need to be offered the opportunity to use the language in their communities. Learning the language is not enough. Only by turning those learning and speaking Gaelic into people who use it every day will this important historic language survive.