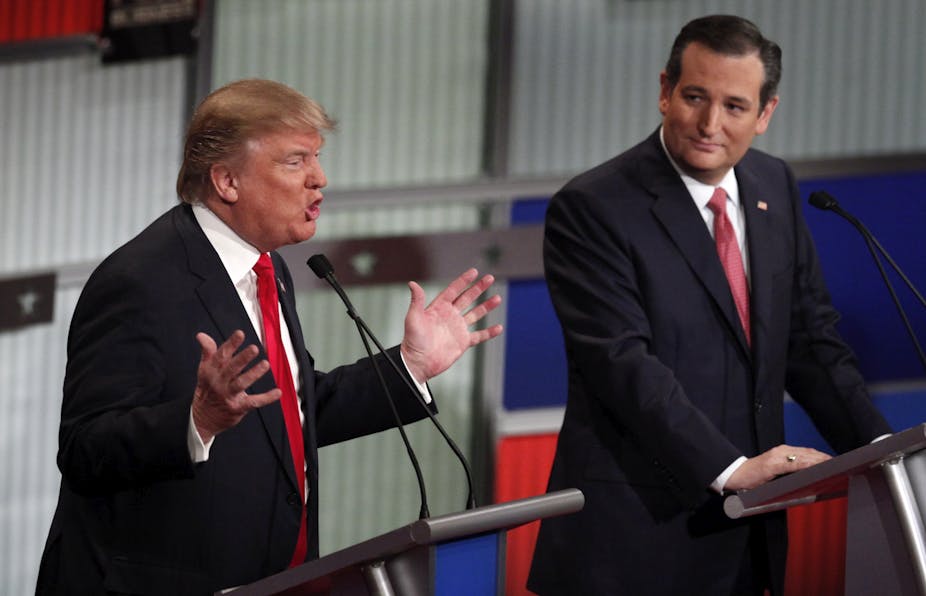

Editor’s note: Seven candidates took part in Thursday’s mainstage presidential debate in North Charleston, South Carolina – the sixth debate between the GOP candidates. Donald Trump, Texas Senator Ted Cruz, Ben Carson, Florida Senator Marco Rubio, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, Ohio Governor John Kasich and New Jersey Governor Chris Christie struggled to stand out in a shrinking field. Our panel of scholars listened and picked one quote to analyze.

Hadar Aviram, UC Hastings

When you look at the “line of migration, you see no women. Where are the women? I see no women… I see strong, powerful men.” – Donald Trump

This is factually wrong. According to State Department data, in the last fiscal year the United States admitted 1,682 Syrian refugees, 77 percent of whom were women and children. But in addition to the inaccuracy, it is also irresponsible reliance on crime stereotypes.

One of the main issues identified by scholars studying the intersection of immigration and crime (“crimmmigration”) is the blurring of these categories by painting immigrants and criminals in associated hues. Since Trump wants to portray refugees as potential criminals, and since crime is considered to be a predominantly male phenomenon, he misleads voters about the demographics.

But the consensus among scholars of immigration and crime is that immigrants commit significantly less crime, per capita, than the native-born.

One way to understand Trump’s obsession with immigrants is with pacification theory. Drawing attention to a demonized “other” creates solidarity against that group, conveniently diverting the public’s attention away from contentious issues such as the impact of deregulation and tax breaks for the wealthy on the middle and working class.

Nathaniel Swigger, Ohio State University

“I’m not going to have something that Ted described in his tax plan. It’s called the value added tax. And it’s a tax you find in many companies in Europe…And that’s why they have it in Europe, because it is a way to blindfolded the people, that’s what Ronald Reagan said. Ronald Reagan opposed the value tax because he said it was a way to blindfold the people.” – Marco Rubio

First, Senator Rubio is correct. Cruz doesn’t call his plan a value added tax, but it would function exactly like a VAT. In fact, many conservatives are concerned because Cruz is essentially proposing a national sales tax implemented in a way that would actually make it less visible to the average consumer.

This portion of the debate was interesting because Rubio went on the attack, unprovoked, against Senator Cruz. Rather than waste energy on the candidates trailing him, Rubio took on the candidate he considers his main opponent.

The tactics provide an interesting view of how the main candidates see themselves at this point in the race. Coming into the debate, the assumption was that Cruz and Trump would spend the debate attacking each other. The other four candidates were expected to focus on each other, competing for the “mainstream Republican” vote. And, indeed, Cruz and Trump had some testy exchanges and traded one-liners early on.

The other half of the debate went in a very different direction. The candidates fighting to become the establishment savior (Rubio, Christie, Bush and Kasich) spent little time on each other.

Rubio has been branded in many circles as the last best hope for establishment Republicans and he was clearly trying to play that part tonight by attacking Cruz. In Rubio’s ideal world, he’ll do well enough in New Hampshire that Bush, Christie and Kasich all drop out. He approached tonight as though that’s the most likely outcome.

David Cook Martin, Grinnell

“No.” – Donald Trump, responding to a question asking if he would rethink his proposal to ban Muslims from entering the country

The other candidates responded with a range of proposals.

Bush challenged Trump to reconsider the cost of alienating geopolitical allies.

Carson proposed reliance on common sense and the formation of a panel of experts to study the matter.

Kasich and Christie proposed, respectively, a pause on the entry of Syrian refugees and banning “radical Islamic jihadists.”

Cruz advocated suspension of entries of all refugees from nations controlled by the Islamic State (ISIS) or al-Qaida.

Rubio suggested the intriguing notion that “if we do not know who you are, and we do not know why you are coming, when I am president, you are not getting into the United States of America.”

The conflation of refugees with immigrants and the reduction of this policy debate to one about security were striking.

The candidates moved freely from discussions of refugees – a legal category defined by UN convention and for which applicants are exhaustively vetted – to permanent immigrants – a status defined by United States law.

Fox moderator Bartiromo didn’t help matters by asking what candidates thought about Trump’s position and erroneously saying that “the U.S. admits more than 100,000 Muslim immigrants every single year on a permanent lifetime basis.” The Pew Research Center, source of this information, refers to “Muslim share of immigrants granted permanent residency status (green cards).” There is no “lifetime basis” immigration status, which can be lost for reasons such as not filing taxes. To become a refugee, applicants must go through an exhaustive and time-consuming legal procedure.

To reduce immigration and refugee policy to a matter of national security overlooks the considerable extent to which the cultural, social and economic success of the United States has been linked to migration, including that of the families of five of tonight’s debate participants. Immigration policy is a complex weighing of security matters, but also of geopolitical interests, economics and the diversity of people and perspectives that have informed U.S. success.

Jennifer Mercieca, Texas A&M

“The New York Times and I don’t have exactly have the warmest of relationships.” – Ted Cruz

Apologia, the speech of “self-defense,” is both an ancient and completely modern form of rhetoric. Indeed, we often find occasions to explain ourselves and our actions and to defend ourselves against our accusers.

Cruz demonstrated his excellent debate skills in one of his first responses of the night as he defended himself from the accusations made by The New York Times.

Cruz had clearly planned and practiced his response to the January 14, 2016 New York Times article alleging he had hidden a substantial loan from Wall Street giant Goldman Sachs during his 2012 Texas Senate campaign. Cruz sought to hide the loan, according to the Times, because he “was campaigning as a populist firebrand who criticized Wall Street bailouts and the influence of big business in Washington. It is a theme that he has carried into his bid for the Republican nomination for president.”

With an undisclosed loan from the very Wall Street company that employed his wife (and donated so much money to Democratic rival Hillary Clinton), it was clear that Cruz was potentially in a bit of an awkward situation.

In response, Cruz denied the facts of the case, used differentiation to explain the circumstances of the loan on his own grounds, and used bolstering to shift blame to despised figures such as Hillary Clinton and The New York Times. Here’s how he did it:

First, Cruz used bolstering to identify himself with the “right” opinions held by his audience: namely, that the mainstream media, The New York Times and Hillary Clinton are all depraved. The article was the “hit piece in the front page of The New York Times,” and “unlike Hillary Clinton, I don’t have masses of money in the bank, hundreds of millions of dollars.” Cruz’s first move of self-defense was to show that he, like his audience, was on the side of good against those who oppose him. It’s an us-versus-them strategy and a way of showing identification with those who will pass judgment.

Second, Cruz used differentiation to separate the Times’ accusations about what had happened (that Cruz had been duplicitous in taking a loan while denouncing the very Wall Street firm who gave him the loan and also hid the loan from Federal Election regulators) from Cruz’s much more heroic version of events: villains (“just about every lobbyist, just about all of the establishment opposed me,” “my opponent in that race was worth over 200 million dollars. He put a 25 million dollar check up from his own pocket to fund that campaign,”) were out to destroy Cruz’s Senate run, so in response Cruz and his wife “took a loan [note that he doesn’t say for how much or from whom] against our assets to invest it in that campaign to defend ourselves against those attacks.” Cruz’s narrative obviously recasts the context within which the loan took place. It was not, as had been reported in the “hit piece,” corruption, duplictious or hypocrisy. Rather, by placing the loan within this new context, it was brave.

Finally, Cruz used denial to reject the substance of the charge against him: “I disclosed that loan on one filing with the United States Senate, that was a public filing. But it was not on a second filing with FDIC [FEC] and yes, I made a paperwork error disclosing it on one piece of paper instead of the other. But if that’s the best The New York Times has got, they better go back to the well.” The loan and the subsequent “paperwork error” were not as they seemed, but were simply a mere misguided paper chase.

It’s a nicely crafted apologia, which may have worked well with a sympathetic audience, but it is unclear if his opponents in the GOP field, Democratic Party, or the mainstream media will be persuaded.