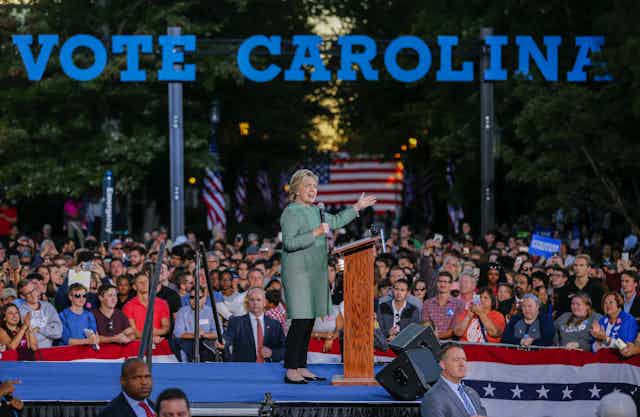

As we enter the final hours of the 2016 US presidential campaign, an interesting trend is noticeable: three states in the US South, traditionally thought of as a conservative Republican bastion, seem to be in play. Here are four reasons why Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina in particular might just surprise us this year.

1: The South has never been predictable

Ever since the American Civil War, the states that founded the Confederacy have been known as the “Deep South”: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Along with the other states who seceded – Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee – they make up “Dixieland”, a region memorialised in song, steeped in tradition, and inseparable from the history of race in America.

From 1880-1948, Dixieland block-voted Democratic all but twice (1920 and 1928). But then in 1948, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina voted for third-party segregationist candidate Strom Thurmond. These southern Democrat states became known as Dixiecrats, opposed to racial integration and determined to protect the southern way of life. They developed a reputation for voting in favour of segregation even when it meant crossing party lines.

In reality the votes of these four states, though sometimes opposing the Democratic candidate, were more in opposition to “everyone else” than they were to their own party. They stood all but alone in support of the Democrats against Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956, in opposition to Democrat and civil rights supporter Lyndon Johnson in 1964, and in support of third-party segregationist George Wallace in 1968.

With the re-election of Richard Nixon in 1972, the entirety of Dixieland voted solidly with the Republican Party. Yet for six of the next ten elections, southern states diverged from the Republican candidate to support one of their own, such as Jimmy Carter or Bill Clinton, and to support a new face, such as Barack Obama. The 11 states of Dixieland have delivered a unified vote in only six of the 20 elections since World War II.

2: Not all southern states were Dixiecrats

We therefore must acknowledge that the bloc of southern states that supposedly vote as one changes from one election to the next.

Neither Florida nor Georgia nor North Carolina were part of the original Dixiecrat cohort. Florida voted differently to the majority of the South in nine of the last 17 elections, thereby earning its reputation as a swing state. Georgia did not support Thurmond in 1948, it supported Clinton in 1992, and stayed loyal to its native Jimmy Carter in 1980 along with only four other states in the entire country. North Carolina, meanwhile, voted for Johnson (1964), Carter (1976), and Obama (2008).

3: Race matters – but not like it used to

To complicate the picture further, these three states’ electorates are steadily becoming less and less white. This is thanks in part to internal migration toward hubs of innovation and intellect, among them the Georgia capital, Atlanta, and North Carolina’s Research Triangle, which now boasts the headquarters of more than 170 companies.

A richer civic life and the creation of jobs in the international market are drawing in a more diverse and more educated electorate. Compared to traditional southern Republicans or Trump supporters, these people are less likely to feel voiceless or to see themselves as outsiders to the economic gains and cultural change that have come with globalisation. They are less likely to support Trump than they were to support 2008’s John McCain or 2012’s Mitt Romney.

Then there’s immigration from abroad. The percentage of the US population who are legal foreign-born residents has been on the rise since 1970; 44% of them are naturalised and therefore able to vote as of 2010. In Georgia and North Carolina, nearly 10% of the population is foreign-born; in Florida, the figure is nearly 20%. These changes mean there are pockets of the electorate unlikely to agree with Trump’s views on immigration.

4: Florida is different

Though one of the southern states who seceded from the union, Florida has never reliably voted with its neighbours. Not for the first time, the state looks like a true toss-up.

Florida’s former governor and failed 2016 candidate Jeb Bush is not voting for either Trump or Clinton. Florida hasn’t broken with the Bushes in a single election where they’ve run, and while there isn’t a Bush on the ballot this year, both his and the family’s feelings are abundantly clear. Both Bush presidents have declined to comment on the race, which many consider to be near-endorsements of Hillary Clinton by their silence alone; former first lady Barbara Bush has explicitly spoken out against voting for Trump.

Trump has also been disowned by a number of important Florida Republicans, including many in the Bush orbit. The list includes such luminaries as senior Florida Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, former Jeb Bush aide and campaign manager Sally Bradshaw, and major Republican donor Mike Fernandez.

Ros-Lehtinen plans to write Bush’s name on her ballot. Bradshaw has formally left the Republican Party and says she will vote for Clinton if the race in Florida is close. Fernandez has in fact gone so far as to publicly endorse and raise money for Clinton, telling Republicans to vote Republican for every office except the presidency.

These leaders have substantial political and financial clout in the state; by withholding their resources, mobilising their networks and speaking out publicly, they have the potential to convince millions of Florida voters to support Clinton or stay home altogether.

It might seem novel or unexpected that so many southern states are in play right now – but looking back over their electoral history, their current leanings are less surprising than we think.