The recent expansion of the Panama Canal marks the latest chapter of a project which has had a profound impact on the country. For over a century, the canal has formed the central axis of politics, economics and social relations in Panama. The project was first launched in 1904, when the US began work on a canal that would connect the Atlantic and the Pacific, and the canal has been the focus of controversy ever since.

But to understand why the Panama Canal remains so important to this day, it pays to take a look at some of the key moments in the project’s history.

1. Rooted in racism

Although the racism felt throughout much of Panama today does not originate in the birth of the canal, it was certainly supported by it. Racism could be found from the very start of the project – while the American and European construction workers were paid in gold, for example, the West Indian and Latino workers received their wages in the less valuable local silver currency. Even when the same work was performed, the worker’s place of origin translated into a significant pay and benefits gap between the silver and the gold “roll”.

The construction of the canal also institutionalised racial segregation by implementing a Jim Crow system, where white American or European managers oversaw racially mixed foremen, who would then supervise West Indian black and mixed race workers.

The canal was built at the height of US racism and imperialism, and it would take the coming of World War II for segregation and discrimination in the Canal Zone – the area including the canal and a few miles either side, which was legally US territory, and so policed and administered by separate authorities – to be questioned.

The US, responding to pressures from the civil rights movement and wanting to improve its relationship with Latin America, abolished the gold-silver system, and racially integrated schools in the Canal Zone. Nevertheless, authorities upheld the segregation between Americans and Panamanians in a system akin to apartheid.

2. First flickers of nationalism

The canal remained under US control for much of the 20th century, and was only fully recognised as Panamanian in 1999. The Panamanians’ struggle for sovereignty can be traced back as far as the immediate post-World War II era. Peaceful student-led protests began around this time and continued for two decades until tensions finally boiled over.

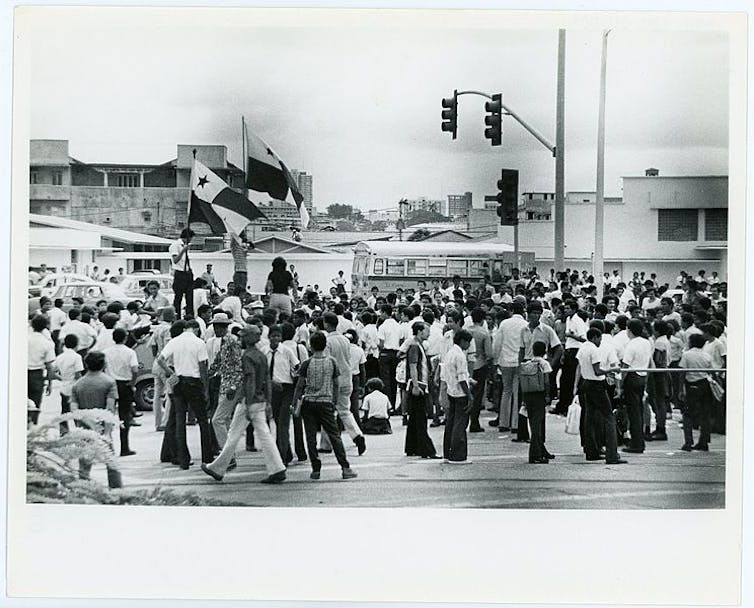

On January 9, 1964, news that an emblematic Panamanian flag had been damaged in a tussle between Canal Zone police and student protesters sparked outrage across Panama City. The students were quickly joined by thousands of Panamanians from the areas surrounding the Zone.

Riots ensued and lasted for two days, by the end of which over 20 Panamanians were dead. This confrontation is considered the first true flare of Panamanian nationalism, where US ownership of the Canal Zone was contested. It was also this event which led Zone authorities to agree to fly the Panamanian flag alongside the US flag in areas of civic interest.

3. Claiming ownership

The next pivotal moment for the canal came while the country was under the leadership of military dictator Omar Torrijos, following a coup d'etat in 1968. Torrijos was committed to wresting control of the canal out of US hands, and is considered one of Panama’s founding fathers for doing so.

After more than four years of negotiations, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, signed by Torrijos and then-US president Jimmy Carter in 1977, committed the US to placing the canal in Panamanian hands by 2000. The Canal Zone was abolished two years later, and the area remained under joint Panama-US control until it was finally handed over to Panama on New Year’s Eve, 1999.

Despite the rampant nationalism of these years, clauses that allowed the US to take military action to protect the canal even after the handover were strongly opposed by civil society organisations. These groups’ leaders were subjected to targeted repression by the military regime that promoted the treaty. The enforced disappearance of student leader Rita Wald – a case which Panama settled before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2012 – is one of many examples of persecution.

4. US invasion

The treaties allowed for military bases to stay open in the Canal Zone, for the stated aim that the canal stayed open, accessible and neutral. The feared School of the Americas – a site where countless Latin American death squad leaders and coup makers had trained – operated on one of these bases.

US intervention into Panamanian internal affairs was not part of the deal. But on the morning of December 20 1989, Panama City awoke to a US invasion led by President George H. W. Bush.

The American code name for the invasion was “Operation Just Cause”, and it was justified as a safeguard to the lives of US citizens in Panama in the wake of the death of a US marine, who was killed a few days earlier in an altercation, as well as to protect of the canal in line with the Torrijos-Carter Treaties.

Operation Just Cause unseated a military regime that had lasted for more than two decades, by removing the de facto head of state Manuel A. Noriega. Yet the invasion and subsequent US occupation left an uncertain number of dead and wounded civilians throughout Panama, the majority of whom were concentrated in the working class neighbourhood of El Chorrillo, which adjoined the Canal Zone.

Panama would not be the country it is today without the canal; these snapshots are just four instances which show the deep social and political impressions it has left on the nation. While the long-disputed issue of sovereignty has been resolved, it’s not yet clear who will gain from the recent expansion of the Panama Canal, and who will lose out. The history of the Panama Canal is one of conflict and division – but the latest chapter is yet to be written, and there’s still an opportunity to learn from the past.