Fracking looks set to arrive in Britain after all. US-Australian energy company Cuadrilla recently announced it may begin producing the UK’s first commercial shale gas sometime in 2019.

The government says that shale plays an important role in the country’s energy strategy. As a domestic resource it can not only can make up for declining gas production from the North Sea, but also help ease concerns about the UK’s dependence on imports, notably against a backdrop of strained relations with Russia as well as recent supply shortages. Supporters of fracking also argue it could fill the gap left by the phase-out of coal power, helping decarbonise the energy system while bringing additional jobs.

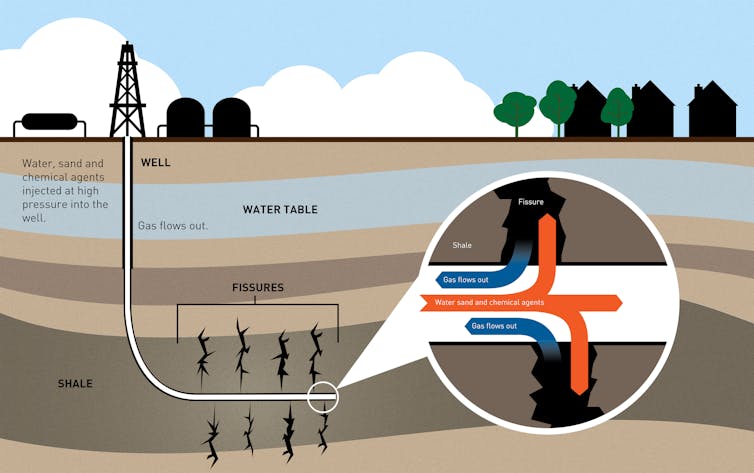

Yet shale gas hasn’t done a great job of selling itself in the UK. Fracking technology itself has come under fire – in order to obtain shale gas, underground rocks are fractured under high pressure and using chemicals. Many people are worried about groundwater safety, the environmental impact and public health, thus leading to protests.

All this raises the question of how to reach an agreement. Is shale gas desirable or not? Is the extra energy worth the environmental damage? Do the jobs created outweigh local residents’ concerns? What’s needed is a shared understanding between the various social, economic and political stakeholders. In short, energy companies need what is known as a social license to frack.

Evidence from Eastern Europe

As my recent research on fracking in Eastern Europe suggests, such a social licence rests on a policy process that all stakeholders see as legitimate, along with public acceptance of a technology that doesn’t often go wrong but could be disastrous if it did.

Although shale gas had been hailed as a “game changer” for East Europeans, given their strong dependence on Russian gas supplies, Bulgaria ended up banning fracking, exploration plans were shelved in Romania, and quietly abandoned in the Baltics. Across the region, environmental activists were joined by ordinary citizens, the Orthodox Church and even a national grain producer association to protest against the alleged threat of shale gas to food security, the environment and the sell-off of “national treasure” to foreign companies such as Chevron. Only a few countries, notably Poland, remained legally open to shale gas extraction, and there fracking was granted a social licence by stakeholders.

Judged by the actual output, shale gas in Poland isn’t exactly a success story. As in Bulgaria, Romania or Lithuania, the country saw foreign majors abandoning domestic shale prospects. The economics simply didn’t add up, geology proved more difficult than expected and the regulatory environment was far from ideal. But public support for the Polish government’s shale gas policies stayed strong, protests remained limited, and people bought into the idea of unconventional energy being of overall net benefit.

Why was that? Governments that pushed for shale in a top-down manner, cared little about public communication and only involved a few friendly faces from the corporate and NGO world faced public opposition – Bulgaria is a good example. By contrast, countries such as Poland that involved those energy corporations already in place, consulted local mayors and ensured some of the profits would remain in the area, saw their efforts pay off.

The policy narrative is another important element. Research I carried out with my colleague Benjamin Sovacool found very different narratives across Eastern Europe. In Poland, shale gas emerged as a national project that could potentially bring economic prosperity and energy security – and this united various stakeholders behind government policy. In Bulgaria and Romania, the discussion of shale gas focused on authoritarian governments and environmental hazards. Poor public bureaucracy meant that people there had little trust in the policy process and began to question the governments’ motivations.

Lessons for the UK and elsewhere

The upshot is that even proving shale gas is economical to extract – in Lancashire or elsewhere in the country – will not be enough to make it happen. Extracting unconventional energy resources at an industrial scale will eventually require a social licence from society as a whole, not just the local communities that are most directly affected. This won’t be achieved simply through bureaucratic processes, such as production permits, or even through a mandate from an election – the social licence requires a much broader buy-in.

Instead, the UK government would be well advised to think up ways to enhance institutional outreach and community empowerment as well as opportunities to facilitate the buy-in of important stakeholders on national and sub-national levels. This may be a cumbersome process, and the outcome may be hard to determine. But it is the only way to lend legitimacy to its policies and to possibly generate the necessary public acceptance for a highly contested technology.

The broader takeaway, however, is that what holds true for fracking also applies to core aspects of the imminent transition towards low-carbon energy. Are people truly ready for massive numbers of new high-voltage electricity pylons? What about enormous new wind farms? Do they appreciate the technology it will take to eventually achieve negative emissions and meet the Paris climate targets? Society as a whole still doesn’t really anticipate anything of the required scale, and a serious jump into a low-carbon world may come as a shock to people used to the status quo.

Changes of that scale should be broadly acceptable to the nation and would therefore warrant a social licence. Starting with appropriate frameworks for fracking may therefore not be a bad idea, and would pay off at larger scale in future.