Drilling in the Marcellus Shale, and in other unconventional oil and gas formations across the US, has led to a boom in domestic natural gas and oil production -– largely due to advances in high volume hydraulic fracturing or fracking.

The environmental and public health risks associated with hydraulic fracturing - a process of pumping a mixture of water, sand, and chemical additives, under high pressure, deep underground to release oil and natural gas from shale formations - have fueled political debates over how best to regulate oil and gas development.

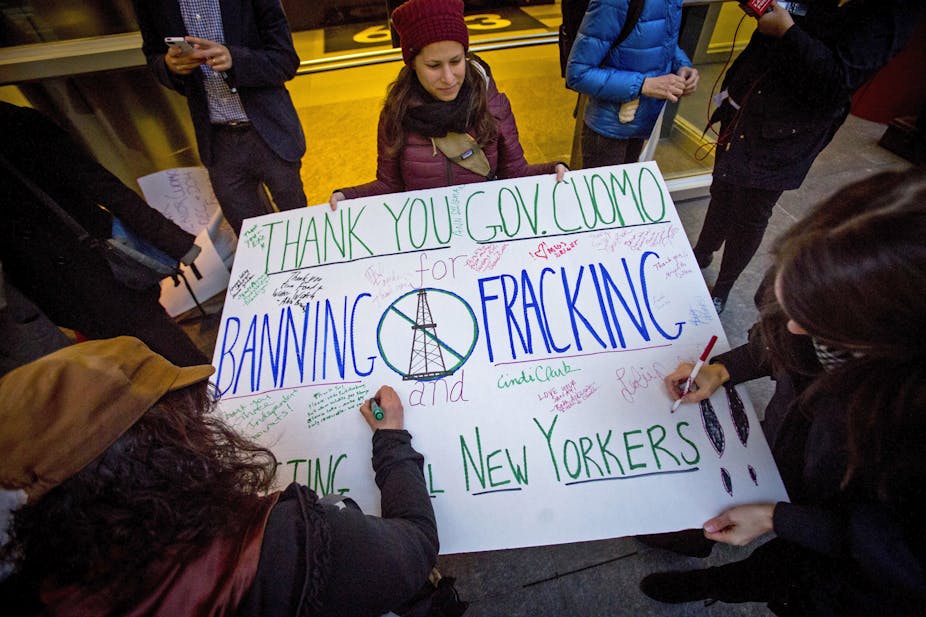

These debates have been particularly polarized in New York. First, in 2008, the state imposed a temporary moratorium in order to carry out an environmental impact assessment, review existing regulations, and conduct a health review. Now, six years later, the Cuomo administration has concluded that the risks are too high and that New York will ban hydraulic fracturing.

The December 17 decision ends an era of political uncertainty in New York. During the past six years, many local governments in the state decided to move forward with their own local bans on hydraulic fracturing. While a number of local governments across other US states have imposed bans or moratoria on hydraulic fracturing, New York has become the second state in the US after Vermont, and the first to overlie a major shale formation, to ban hydraulic fracturing altogether.

This raises two important questions. What made New York’s ban politically feasible? And will other states follow suit and ban fracking?

What makes New York special?

The decision in New York may well have been informed partly by the science in the state health study but science is generally not the key factor in political decisions.

Political decisions are made at the intersection of values, interests, and identities. Making successful ones requires good timing and building support and minimizing opposition. For Governor Andrew Cuomo, the stakes were high. He was up for reelection in 2014, so a decision one way or the other might have affected the election results. He had to be careful not to anger any major voting base and yet, at the same time, show leadership.

As our research has shown, the opposition to hydraulic fracturing has been particularly strong in New York relative to other states. A survey we administered in the fall of 2013 to politically engaged people in New York (including those with government, nongovernment and industry affiliations) shows little middle ground. This is not the case in Colorado and Texas, for example, where similar studies we conducted show a larger proportion of moderate positions.

Given that Democrat Andrew Cuomo does not have a lot of support in the middle, he would inevitably be caught in the crossfire in making a decision. He had to align with one side or the other.

Those in favor of fracking in New York include some local governments, mineral rights owners, and the oil and gas industry. In opposition are many local citizen-based groups and environmental and conservation groups. Our research also shows, however, that although the oil and gas industry may have financial resources, those opposed are better mobilized, better networked, and orchestrate more political activities that can attract sympathetic observers and gain political allies.

A critical court case

Gaining political leverage involves more than public performances. It requires the capacity to influence government. While opponents to hydraulic fracturing have proven successful at influencing local governments across the state, the durability and legitimacy of that influence remained uncertain until a recent state court decision upheld the constitutionality of local bans. This court decision also provided an opportunity for the Governor to align with a powerful coalition - namely that against fracking. Indeed, without the state ban, it’s likely local governments would have had to go ahead without the Governor’s support.

While the opponents of hydraulic fracturing were gaining momentum in New York, the supporters had fewer political opportunities to gain a foothold on the debate. In part, this is a result of declining prices for natural gas prices, New York’s more limited shale resources compared to neighboring states and the fact that the oil and gas industry historically has not been a major economic base in New York. All these factors arguably inhibit New York’s potential for expansive economic development from shale gas, at least in the near term.

The rest of the country…

New York is obviously a special case. Whether other states now follow suit with state-level bans against hydraulic fracturing is an open question.

In states where shale development is active and the economic opportunities are still strong, such as Colorado and Texas, we would not expect to see the same opportunity structures in place to follow a similar path. But the nation is watching and learning from the ban in New York, especially as public opinion remains fairly divided on the issue.

For those supporting hydraulic fracturing, the New York ban is a threat that will likely lead to entrenchment and intensification of political resolve. For those against hydraulic fracturing, the New York ban is a possible path for victory by showing how to mobilize supporters and pressure government.

While the political uncertainty associated with the moratorium may have been resolved in New York, the debate is now likely to escalate across the nation.