Let’s face it, Thursday evenings on ABC television are not quite the same any more. The mesmerising, idiosyncratic sketches of Clarke and Dawe are now consigned to Australian television history. Still, Sammy J has taken the spot, and the good news is that the spirit of Clarke lives on. Sammy J’s gormless, football coach character, the strongman at the helm of the “Blue Ties”, delivers the rebukes to our politicians in a register we all recognise. The sketches are clever, dry and whip smart. The coach is comical with his blokey, narcissistic armoury of quips.

Sammy J is versatile too. One night in the guise of an auctioneer for “Sothejays Auction House”, he sold off most of the LNP cabinet – seeing off the pre-election deserters. In another episode, he diligently sold off the ABC, with “Channel 9, Network 10, the IPA, Mark Latham, Newscorp and the Communications Minister” assembled for this “steal, after the 254 million dollar cuts to the formerly publicly owned broadcaster, now broken down, torn apart and ready to be sold off to the highest bidder”.

The satire in those two Sothejays episodes is seamless, as it was in so many of the two-minute gems delivered by Clarke and Dawe. We recognise and admire the comic ingenuity each week because the sketches refer to the events that we’ve all just witnessed in the news. Our despair, rage and incredulity, turns to delight and we can breathe again after the release of laughter at seeing our pollies skewered.

Edna as pioneer

Barry Humphries pioneered topical, referential satirical comedy in Australia in the 1950s. Carol Raye, Max Gillies, John Clarke, The Chaser and others developed it and brought innovation to satire in their characters and programs. The flipside of topical satire and its comic immediacy is that the work dates immediately. The elements – the factual reference points of the satire – become hard to trace over time, particularly for new audiences, and then eventually – sometimes quite quickly – the performer is consigned to history.

But the style and power of the satire, the achievement of the performer and the innovation that the individual brings to their form and the genre, often informs the next generation, sometimes directly, and sometimes indirectly. In that way the original contribution and its spirit lives on in the traditions that follow, building a distinctive comic culture over time.

In 1955, with the Olympic Games to be staged in Melbourne the following year, the organisers were fixated on the problem of housing the influx of visitors, and the fact that the athletes’ village in Ivanhoe was not yet finished. In a parody of the Australian, and specifically Melbourne tendency to pronounce “average” as “everage”, Barry Humphries called his plain and timid character Mrs Norm Everage or Edna, after the kind lady who had looked after him as a small boy.

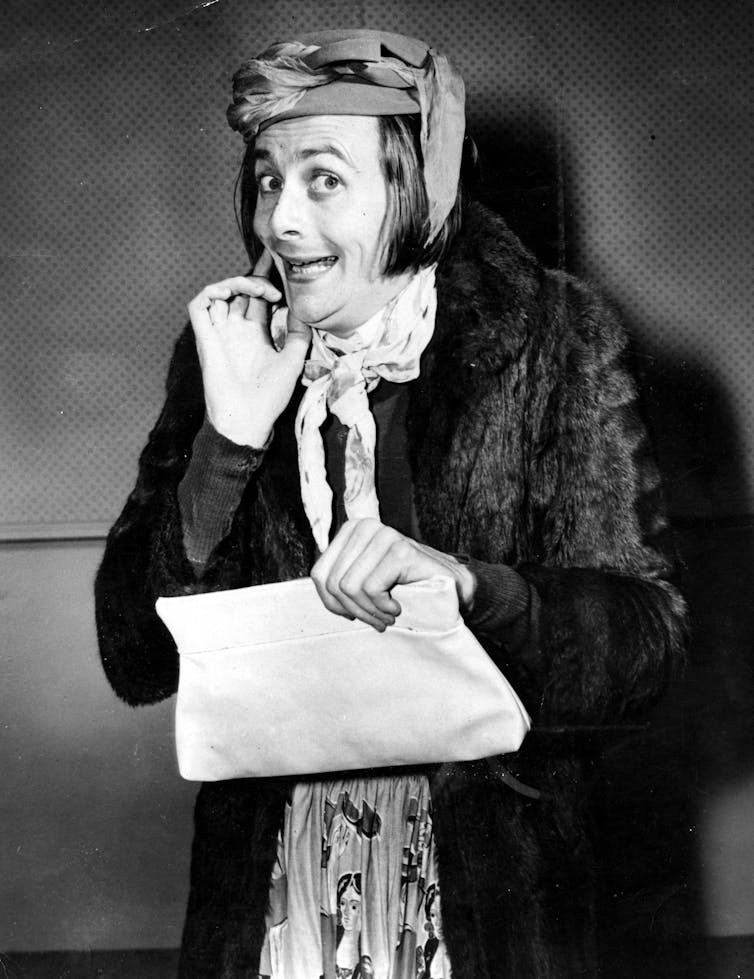

In a Christmas revue sketch directed by Ray Lawler, Humphries dressed as Edna Everage offered to open her home in Humouresque Street, Moonee Ponds to a visiting athlete, and asked the most preposterous questions about the visitors. In the stage sketch a government official listed the nationalities of the potential guests and Edna responded with bigoted comments about all of them.

The sketch was called “The Olympic Hostess” and Noel Ferrier played Mr Hopechest, the official interviewing Mrs Everage. In 1955, she was shy in comparison to her later incarnations. She described her bedroom with its newly painted duck-egg blue walls and chenille bedspread.

“But you surely don’t wish to share your bedroom with the athletes?” the official exclaimed. “Oh, goodness, no. Norm isn’t as sporting as all that,” she replied.

Mrs Everage stated that she would prefer to host someone from the Commonwealth, and that she didn’t mind if they were “a little tinted”, “perhaps someone from Ceylon”. She felt sure that meeting an athlete would be good for her son, Kenny, and broaden his horizons.

The 21-year-old Humphries borrowed a yellow felt hat belonging to his mother for the sketch, one that Louisa Humphries had intended to wear to the races. Edna wore a twinset underneath a light beige coat, the kind of garment women wore into the city on the tram to cover their bare arms.

The tall, spindly-legged Humphries spoke to the audience in their own vernacular about their own homes. It was an important moment for Australian theatre, but the audience was slightly stunned, and the sketch was regarded as only moderately successful. Barry never imagined that he would perform the character again. Little did he realise that this 1950s “Mrs Average” would take on a life of her own.

On John Laws’ Friday night television variety show, Startime in 1962, Humphries introduced Mrs Everage as a “a very close friend of mine”, and then appeared in a coat and a small hat, extolling the virtues of plastic gladioli, and declaring that it was wonderful to be back in Australia. Humphries himself was back in Australia after a few years in London for his touring stage show, A Nice Night’s Entertainment.

The studio audience for Startime laughed loudly at Mrs Everage. Edna’s commentary on Australian manners would become the centrepiece of an ongoing drama devised by Barry on the subject of Australia over the next 50 years. His anarchic, sometimes cruel comedy still raises eyebrows today and enrages his critics.

He ran into serious trouble in 2003 when Edna insulted Hispanics in the US in a column for Vanity Fair, instructing readers to

Forget Spanish … Who speaks it that you are really desperate to talk to? The help? Your leaf blower? Study French or German, where there are at least a few books worth reading, or, if you’re American, try English.

Swamped by complaints the editor attempted to explain the satire, calling Edna “an equal opportunity distributor of insults”.

In the last few years, Humphries and Edna have crossed the line several times. The actor called transgenderism a “fashion” in The Spectator earlier this year, causing offence with comments such as: “How many different kinds of lavatory can you have? And it’s pretty evil when it’s preached to children by crazy teachers.” The Barry Award, named after Humphries, is no more, after some controversy.

Public taste has changed and that is that. Humphries is primarily of historic interest now. That’s how satire and comedy work. It’s not just the references that date in topical satire. Audiences are powerful, and if they feel insulted they can shut down a comedian.

Clarke and Bazza

John Clarke’s career began in earnest through first hand observations of Barry Humphries on and off the stage. Clarke met Humphries in the early 1970s in London, and it was through this meeting that he began to glimpse a future for himself in comedy.

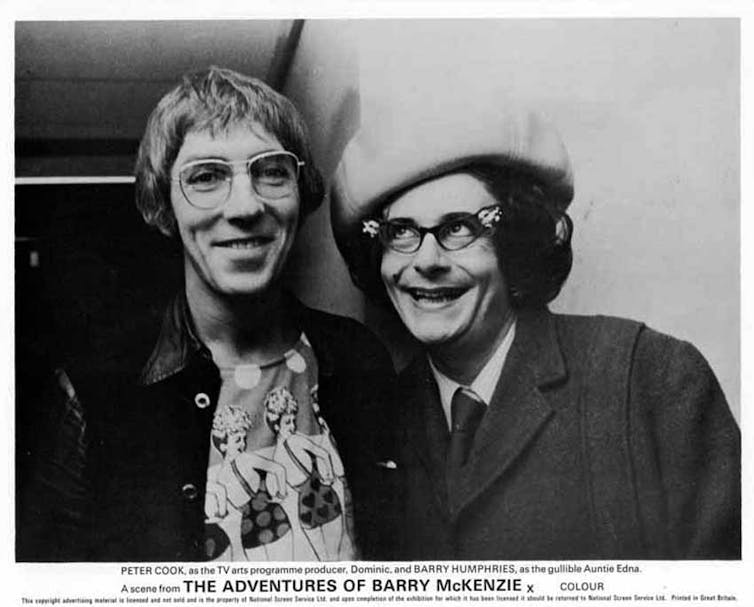

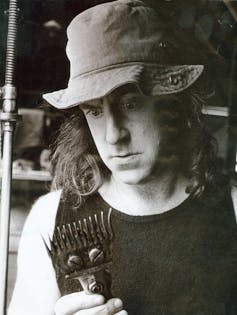

Clarke was working as a van driver and spending his afternoons and evenings in the pub when his friend, Ginette McDonald, convinced him to audition for the young Australian director Bruce Beresford, who, she’d heard, was making a film in which a lot of young men were required.

Clarke had appeared in revue theatre back at home in New Zealand but was reluctant to attend an audition. But when he read the script for The Adventures of Barry McKenzie he roared with laughter, and was awestruck by the talent of the three men driving the film: Beresford, Humphries and Nick Garland. Garland, a New Zealander, had drawn the cartoons for the Barry McKenzie comic strip, on the which the film was based.

During the filming, Beresford and Humphries shepherded Clarke along. John spent hours talking to Humphries about what Humphries had read as a young man. The audacity of this gangly, long-haired, young Australian and his vivid humour struck Clarke immediately, and was to have a huge influence on Clarke’s evolution as a performer.

Clarke noticed that Humphries performed for a world audience, and while he parodied the cultural cringe, he and Beresford asserted their equality with everything and anything British at every opportunity. Clarke felt that he could be himself with these men; better still he could be himself in the film, appearing in the pub scenes singing and drinking with Bazza McKenzie.

Being permitted to play himself was the key to Clarke’s performance style and his future as a satirist: not only did it offer him a strangely comforting armour, but it provided the perfect satirical weapon and a mode of directly addressing the audience.

The experience of working with Humphries and Beresford emboldened Clarke in the long run and he returned to New Zealand to start work as a performer. By the end of the year, Clarke had made his first television appearance as Fred Dagg, an endearingly dishevelled sheep farmer who went on to charm audiences in New Zealand and Australia for years to come.

Gillies, Hawkie and the glory days

John Clarke carefully explained to me in several interviews I conducted with him over the years that if he had not experienced that work with Humphries, he would not have created Fred Dagg, or had the confidence to create satirical television. He always took time to observe. When he moved to Australia in 1977 he took things slowly.

He encountered the masterful mimic, Max Gillies, and at Gillies’ invitation contributed to the scripts of The Gillies Report, a hugely popular weekly satirical television sketch show on the ABC that featured Max playing all the politicians of the day, and John as a news reader, amongst other roles. Max’s powers of mimicry and rich, politically potent satirical impersonations seized the imagination of the whole country; the hyper-theatricality of the sketches and rollicking musical production numbers struck a chord with viewers.

Gillies had first created a magnificent version of Bob Hawke when the former ACTU president rose to power, playing the charismatic, savvy, effervescent man of the people with such flair that many mistook him for the Prime Minister. Gillies even appeared as Hawke in Hawke’s presence, addressing the North Melbourne Foootball Club grand-final breakfast in character as the PM. It is unusual for performers to appear in the presence of those they impersonate, and it was the first and only time in Australian history that a Prime Minister has allowed it.

Yet Hawke’s ambivalence was clear to observers and to Gillies that day. Shaking hands with everyone at the high table, Gillies, dressed in his silver suit, large cufflinks and expensive wavy-haired wig, ran the gauntlet of the Club President, the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, finally greeting the man himself, Robert James Lee Hawke. The leering Prime Minister grabbed Gillies’s hand so vigorously his wrist throbbed and before he knew it Hawke had pulled him into a tight, face-to-face, with cameras flashing all around them.

Gillies blinked as Hawke suddenly let go of his hand and brought his fist to Max’s nose, punching him in a stinging bop, as he turned to approach the podium to give his performance of the man who had just hit him. It was a playful but not painless pre-emptive “alpha male” warning to the actor. It’s difficult to imagine such a scenario today but who knows, with “ScoMo” and “Albo” at the helm.

Manning Clark cast Humphries among the mythmakers and prophets of Australia as he witnessed the man “enriching the culture which had been dominated by the straiteners”. Peter Conrad described Humphries’ adolescence as a “one-man modern movement”, and the American critic John Lahr admired the art of the clown who takes the public to the “frontiers of the marvellous”.

Anyone who saw Humphries perform his one man shows in the glory days knows that Lahr was right. But that is now history.