James Joyce once said to his friend Frank Budgen:

If there is any difficulty in reading what I write it is because of the material I use. In my case the thought is always simple.

“Difficulty” is an understatement for the reader’s experience of the bewildering Ulysses, with its notoriously experimental styles and form, extravagantly wrought language, and approach, in which nothing is “stupidly explained” – a stance that the young Joyce had praised in his idol, Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen.

Declan Kiberd’s book Ulysses and us: The art of everyday living explores the somewhat generous proposition that Ulysses is a “book of wisdom” about the everyday world. The key to understanding the genius and richness of Ulysses, I suggest, is Joyce’s inspired “simple” thought of interjecting into this “one day in the life” of a city — its smells and sounds, its sandwichboard men, jingling brass bed quoits, gorgonzola cheese and burgundy, its trams and pubs — an epic apparatus of correspondence that draws us to explore the vast canvas of the work.

By “correspondence”, I mean where one element – say an object, sensation, or cognition – resonates with another, forging a meaningful connection. The most overt form of this is the referencing of Homer’s Odyssey throughout the novel’s 18 episodes. Homer tells the story of Odysseus (the Roman form of this name being “Ulysses”), a guileful Greek warrior, and his epic adventures throughout the Mediterranean region on his way home to Ithaca, to be reunited with his kingdom, his constant wife Penelope (whose virtue is besieged by suitors), and his son Telemachus.

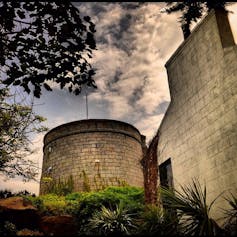

The correspondences between this story and a rather uneventful day in Dublin are by no means self-evident. Odysseus’ counterpart in Ulysses, Leopold (Poldy) Bloom is an advertising salesman who leaves home to go to a funeral, and to work, in the knowledge that his wife Molly (Penelope) intends to have an affair that day with Blazes Boylan. Meanwhile, the young poet and intellectual Stephen Dedalus is living a somewhat bohemian life in the Martello Tower with the blasphemous, garrulous, amusing Buck Mulligan. The paths of Dedalus and Bloom cross during the day and night until they meet and have a wide-ranging conversation. Bloom takes care of a now drunken Stephen, and invites him home to stay the night.

The correspondences then, do not necessarily entail finding similarities between everyday life and the epic, but they can evoke connections and comparisons that lead us to reflect. The effect is often comic (Odysseus, participant in the great siege of Troy is reduced to Bloom besieging potential advertisers), in a book of which Joyce said “there is not one single serious line in it”, but some correspondences resonate deeply.

For instance, Poldy misses his natural son Rudy, whose death has badly affected his marriage. Stephen (corresponding to the son Telemachus) resembles his literal father rather too much: the verbally inventive, intemperately drinking Simon Dedalus. He could perhaps use the tempering touch of caring, practical-minded Bloom. And even a marriage marred by infidelity is, in Ulysses, something to celebrate. Learning how to read Ulysses also leads us to read human experience in ways that defy conventional expectations.

Dirt for art’s sake: Ulysses’ reception

Ulysses’ electrifying novelty polarised opinion from the outset. After it was published by Sylvia Beach in Paris in 1922, T.S. Eliot called it the

most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.

Many readers were unprepared for the strong language, detailed attention to bodily functions, including female orgasm, and Molly Bloom’s uninhibited discourse. Not only does this modern-day Penelope defy the Homeric virtue of constancy, but she revels in her transgression: (“yes and damn well fucked too up to my neck nearly”). For many, including those who had read the book only partly or not at all, it was chaotic, formless, or as Joseph Brooker notes, a latrine, a “phone book”, a desert “as dry as it is stinking”.

First published by The Little Review, in serial form, it was the subject of an obscenity trial and was banned in the USA, then the UK. In 1933, however, Justice Woolsey’s decision in the US District Court observed that Ulysses was not “dirt for dirt’s sake”.

In Australia, the news that it was obscene, and the news that it was not, took longer to break. The Brisbane Courier Mail of 19 September 1941 claimed that “after being freely available to the public of Australia for the last 20 years”, Ulysses had been “banned by the Minister for Customs”. The ban was not overturned until Gough Whitlam’s 1972 accession to power. (Gough once gave a copy of the banned book to his wife.)

A damaged love story

One of Joyce’s enduring creations is that of a community of people worldwide who meet to read, discuss or dramatise Ulysses each June 16. Ulysses is not only Joyce’s time capsule of Dublin on that day in 1904, but a monument to his beloved partner Nora Barnacle. It was on June 16 1904 that Nora first “walked out” with Joyce, and administered what he described to her in a letter as a sexual “sacrament”. Later that year they eloped in self-proclaimed exile to the Continent.

However, on a rare return trip to Dublin five years later, Joyce’s friend Vincent Cosgrave hinted that he had enjoyed Nora’s favours before Joyce did. Joyce, agonised with doubt, was shattered. Ultimately a good friend, J.F. Byrne, reassured him that the story was untrue. Years later, Joyce assigned Byrne’s address to Bloom: 7 Eccles Street. Joyce’s crisis of faith over Nora’s fidelity had, somewhat masochistically, inspired the central event of Ulysses. And indeed, Peter Costello’s thoughtful biography of Joyce suggests that Cosgrave’s boast was not necessarily empty.

The “plot” of Joyce’s epic is otherwise just two cartographer’s lines, the intersecting paths of Bloom and Joyce’s alter ego Stephen Dedalus. Dedalus believes himself cast out of the Martello tower by flatmate Buck Mulligan, and surrenders the key to him. Bloom forgets his key. Both are symbolically usurped; Dedalus does not know where he will spend the night.

The first six episodes of Ulysses follow firstly Dedalus’ and then Bloom’s mornings, using internal monologue to reveal the protagonists’ thoughts. In later episodes, the structure, language and logic of the writing itself undergo a dizzying series of experiments. These developments constitute Joyce’s own “Odyssey of Style”, which takes the reader on a wild ride.

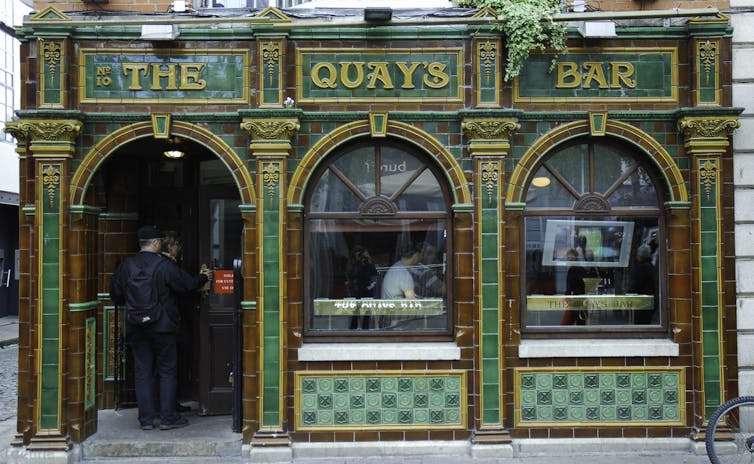

The seventh, breakout chapter for instance, “Aeolus”, is centred on the offices of the Freeman’s Journal and Evening Telegraph. Aeolus is associated with the Greek god of the winds, whom Joyce mischievously associates with the art of rhetoric. This was set out in a table of correspondences for each episode that he used to explain his design to a mystified public. Aside from the preponderant gossip and banter, in this episode both great oratory and nauseatingly flowery writing receive extended attention — the latter to hilarious effect, as Simon Dedalus and other layabouts damn the purple prose splenitively before, parched by their exertions, inevitably adjourning to the pub.

A panoply of rhetorical devices is employed in the episode, which is punctuated by a series of newspaper-style captions or sub-heads, and incorporates multiple references to air flow, as various blowhards in the offices shoot the breeze or, in the case of declining lawyer J.J. O’Molloy, seek to “raise the wind”: ie, borrow some cash.

But what is most impressive in this episode is how Joyce extracts meaning through adroitly signalled chains of correspondence that, in the political climate of 1904, make pointed connections between Ireland’s history of subjection (symbolised in Nelson’s Pillar and the GPO, from which “His Majesty’s vermilion mailcars” circulate), and her nationalistic aspirations. Chillingly, the episode is set at the time (12 noon) and place of the 1916 Easter Uprising. A gloomy proclamation by editor Myles Crawford, “We’re the fat in the fire” proves prophetic. Indeed, these offices did burn in 1916. Joyce had begun planning this episode in 1917.

Following episodes include a parodic history of English literature (“Oxen of the Sun”) and a phantasmagorical absurdist drama set in seedy Night-Town (“Circe”) where even objects such as gongs, soap and gas jets get speaking parts. Impressively, Joyce even wrings poetry and beauty out of an apparently technical and scientific mock catechism (“Ithaca”), which includes an inventory of seemingly every Bloom possession.

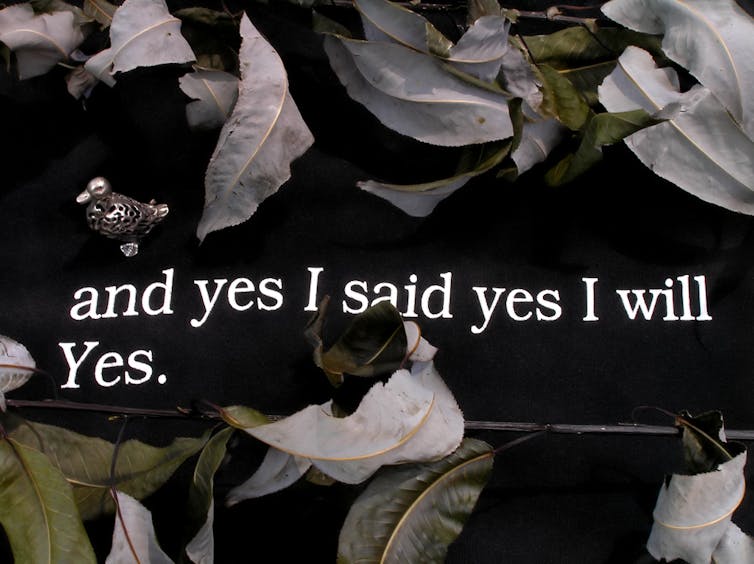

Lastly, there is the justly famous tour de force of Molly’s unpunctuated stream of conscious monologue (“Penelope”), the subject of countless memorable rehearsed readings in Bloomsday activities. “Penelope” is an epic in its own right, in which Molly reviews her day, past lovers, Poldy himself. Molly is accorded the last word.

Ulysses by correspondence

Joyce likely derived his principle of correspondence from multiple sources, although he adapted it to his own purposes. His early interest in mystical and hermetic philosophy followed the loss of his fervent Catholic faith. Two early influences on Joyce were the poet William Blake and the Swedish philosopher and theologian Swedenborg. Both were interested in the idea of correspondence between the material and divine realms, and the spiritual principle that earthly conditions reflect higher realms.

Bloom expresses a parallel idea in a passage from the “Calypso” episode, where he visits the pork butcher to buy a kidney for breakfast.

Leaving the shop, Bloom responds to an everyday object:

Watering cart. To provoke the rain. On earth as it is in heaven.

Mysteriously, the very next line records that

A cloud began to cover the sun slowly, wholly. Grey. Far.

Even mundane experience need not be meaningless. Take for example, the references to meat in “Calypso”. In Homer, Calypso is the goddess who detained Odysseus on her island for years for her carnal pleasure. For Bloom, the sight of sausages in the butcher’s window is answered by his desire to perv on the “hams” of the next door girl, whom he in turn associates with a tattered religious garment, a scapular, “defending her both ways”. For Joyce, church and policing are closely linked; both are in the confession business. Bloom now indulges in a memory, or fantasy, of the girl enjoying a cuddle with a policeman in Eccles Lane: “They like them sizeable. Prime sausage.” Later, his disparate musings on meat link us to universal themes of sex, death and advertising.

As a young man, Joyce had read Lamb’s The Adventures of Ulysses and was attracted to its supernatural elements. Ulysses is punctuated by curious parallels between Bloom and Dedalus, and various synchronicities: Poldy thinks about Blazes Boylan, who immediately appears; Stephen, who has complained about Ireland’s three masters, in a later scene turns his head back suddenly to see a three-master ship. These are not the contrived coincidences of Dickens but realistic experience, attended to in the spirit of wonder.

Bloom in wonderland

Ulysses is a feast of a book. The walls and the streets echo with laughter, song and banter. The life lived in the shops and pubs and workplaces, the décor, the clothes, the advertising signs and appliances, is brought back to life in these pages, filtered through the minds of artistic Stephen and scientific but “wonderstruck” Bloom. “Wonder” is one of Bloom’s favourite words; there is much to wonder at.

In the first episode, Stephen stands at the stairhead on the tower, haunted by visions of his dead mother:

Buck Mulligan’s voice sang from within the tower. It came nearer up the staircase, calling again. Stephen, still trembling at his soul’s cry, heard warm running sunlight and in the air behind him friendly words.

Is this mere hallucination, the product of a stressful night, or the continuance of unresolved grief at his mother’s death? And what can we make of Bloom’s parallel experience that same morning?

Quick warm sunlight came running from Berkeley road, swiftly, in slim sandals, along the brightening footpath. Runs, she runs to meet me, a girl with gold hair on the wind.

Since a cloud has just begun to cover the sun, it seems likely that Stephen’s vision occurs at a similar time to Bloom’s. Kiberd’s beautiful suggestion that this is Bloom’s “Homeric vision”, is appealing. Equally, he could be hallucinating his absent daughter Milly, but then how do we explain Stephen’s similar vision? A definitive answer is not necessarily achievable.

Whatever we make of it, Joyce’s epic resembles the “open work” spoken of by Umberto Eco: one that invites us to explore it for ourselves. The supreme virtue of Ulysses is that it so richly rewards the considerable exertions required of us.

Some relevant resources:

Which edition of Ulysses?

Choosing the preferred edition of Ulysses is not a transparent choice, given the vexed publishing history of this book, and the so-called Joyce Wars. Many critics prefer Hans Walter Gabler’s corrected text (1986). Danis Rose’s attempt to find a more definitive text has met with mixed reviews. Jeri Johnson’s introductory essay to the book in the Oxford World’s Classics series is excellent, and this edition also has some very useful notes on each chapter at the back. Take note however that this is a reprint of the original typesetting of 1922 and so is prone to some possible textual errors.

Audio resource

An excellent audio recording from an ensemble cast that really brings the book alive. In my view, the best way to approach Ulysses: Free downloadable files at: https://archive.org/details/Ulysses-Audiobook

Guides and commentary

It has been said that one does not read Joyce, one studies Joyce. Certainly there is no shame in taking a guide book with one, when embarking on a reading odyssey. Bear in mind however that guides can be a mixed blessing: they can over-explain and over-interpret, or present us with an overwhelm of information.

A popular, updated guide to Ulysses:

Blamires, Harry. The New Bloomsday Book: A Guide through Ulysses 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 1996.

A reasonably demanding guide to and interpretation of Ulysses, from an influential Joyce critic:

Ellmann, Richard. Ulysses on the Liffey. London: Faber and Faber, 1972.