Recently, the International Criminal Court sentenced a Malian militant to nine years’ jail for his role in destroying heritage sites in Timbuktu. The conviction was the first of its kind. Will other such cases follow, dealing with the destruction of priceless artefacts at Palmrya in Syria or in other war zones?

And what, more broadly, is the fate of our cultural heritage in an age driven by the imperative of continual global economic growth? Are wartime atrocities the chief threat to cultural heritage? Or is it, in fact, everyday development in a rapacious world?

The ICC case concerned the destruction of World Heritage sites in Timbuktu, Mali, in 2012, by al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamist insurgents. The former militant, Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi, admitted that he had directed the destruction of 14 holy 15th and 16th-century mausoleums considered blasphemous by the Islamists. The presiding judge, Raul Pangalangan, described targeting Timbuktu’s cultural patrimony as

a war activity aimed at breaking the soul of the people.

Of course since time immemorial, people have been destroying and looting other people’s places and stuff – what we’d now call cultural heritage – through both hostilities and ostensibly peaceful “development”. You can see the evidence all over the world, in cityscapes, museum collections and even whole landscapes as much as in specific archaeological sites.

In recent years, though, the link between extremism and the looting of cultural heritage has become more pronounced. Blood antiquities fund conflict, just like blood diamonds. In April, the Antiquities Coalition in Washington DC launched a report Culture under Threat, which contained a set of recommendations to the US Government concerning the nexus between looting and violent extremism. The panel included various heritage professionals, ambassadors and the like, but also people from the intelligence and Special Forces communities.

Some of their evidence was jaw-dropping, such as the ISIS paperwork regarding looting permits for Palmyra. Not only were there the permits themselves, which authorised looting by so-and-so in area such-and-such, but there were also applications for extensions of the permits owing to problems in moving the volume of antiquities flooding the illicit market.

These were not scrappy handwritten notes, but duly notarised printed documents on “official” letterhead. The bureaucratic banality of evil!

The vast scale of the looting revealed was staggering too, with photographs of heavy earthmoving equipment excavating tons of archaeologically-rich deposits to be sifted through for saleable artefacts.

It’s hard to know exactly how much money ISIS and similar groups make from blood antiquities, but it’s substantial. As one of the Special Forces people said: a historically-valuable artefact may now be seen chiefly in terms of the ammunition it will buy for ISIS.

For this reason, governments around the world are starting to clamp down heavily on heritage trafficking. There’s long been some effort in that direction: the Italians, for instance, have had a specialist police unit, now known as the Carabinieri Art Squad.

These days, though, in the eyes of intelligence and law-enforcement agencies, heritage ranks right up there with arms and human trafficking, as the same extremists and criminals are frequently involved in all three. Monday it’s guns. Tuesday it’s sex slaves. Wednesday it’s blood antiquities.

While this intense focus on crime and security obviously attracts headlines, there is also a compelling link between heritage, identity and wellbeing. For instance, the Australian Government’s recently-released Australian Heritage Strategy points out that the Productivity Commission

found that reinforcement and preservation of living culture has helped to develop identity, sense of place, and build self esteem within Indigenous communities.

Such findings are not restricted to colonised minorities. This year, a department of the UK Heritage Lottery Fund released a research review of the “values and benefits of heritage”. About 70% of respondents believed that

heritage sites and buildings play an important part in how people view the places they live, how they feel and their quality of life.

In my observation, much the same would be found in Australia and most other parts of the world. In broad terms, it was concern for such matters that drove the Mali prosecution.

Heritage destruction as a war crime

The sites destroyed by the Islamists in Timbuktu included the 16th century mausoleum of Sidi Mahmoud, leader of the city’s celebrated Sankore University, and the shrine of Sidi Ahmed ar-Raqqad, a scholar and Sufi mystic who wrote a treatise on traditional medicine over 400 years ago.

Under the Rome Statute governing the International Criminal Court, war crimes include intentional targeting of historic monuments. Although this is the first time the ICC has prosecuted war crimes on this basis, its action is consistent with the various Hague conventions on war going back to the late 1800s.

The Mali trial builds on jurisprudence developed in the Nuremburg trials after WWII and on the war-crimes prosecutions by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia of those responsible for destroying cultural property in the Balkans war in the 1990s. As in the case of Mali, the cultural World Heritage status of Dubrovnik’s Old Town was a determining factor in the convictions of Yugoslav People’s Army commanders Miodrag Jokić and Pavle Strugar following their 1991 shelling of the city.

In the Mali case, concern has been expressed that the ICC’s sole focus on heritage “stuff” is misplaced and should be expanded to include matters such as torture, rape and murder.

The International Federation for Human Rights, for example, welcomed the verdict but contended that “this victory does leave something to be desired”. The Federation called upon the ICC prosecutor to continue her investigations and to prosecute the perpetrators of other crimes committed in northern Mali, in particular, sexual and gender-based ones.

However, as Fatou Basouda, the ICC’s prosecutor, stated in September 2015 in relation to the Timbuktu case:

Let there be no mistake: the charges … involve most serious crimes; they are about the destruction of irreplaceable historic monuments, and they are about a callous assault on the dignity and identity of entire populations, and their religious and historical roots… It is rightly said that ‘cultural heritage is the mirror of humanity’. Such attacks affect humanity as a whole.

The importance that the prosecutor places on identity and dignity – in a word, wellbeing – is something that should focus our minds when we are discussing the place of heritage in other circumstances, even in “everyday” situations.

‘Everyday’ heritage destruction

The destruction of heritage in the course of “everyday” development, in fact, does vastly more damage than war. This is either through large-scale projects such as mines or dams, or the cumulative impact of industrial expansion and smaller-scale projects such as housing and tourism developments.

One high profile international example is the Ilisu Dam on the upper Tigris River in southeastern Turkey. The project will create a 300 square kilometre reservoir that will force the resettlement of tens of thousands of mostly Kurdish people from nearly 200 villages. The dam will also flood the extraordinary historic town of Hasankeyf, parts of which date back 12,000 years.

Despite being declared a major national monument by Turkey in 1978, Hasankeyf was identified by Europa Nostra, Europe’s peak heritage organization, as one of Europe’s “7 Most Endangered” heritage sites in 2016. Early in the long-running campaign to save the site, Turkish government engineers dismissed heritage concerns, stating that the dam was more important to the nation than some old minarets and a few caves.

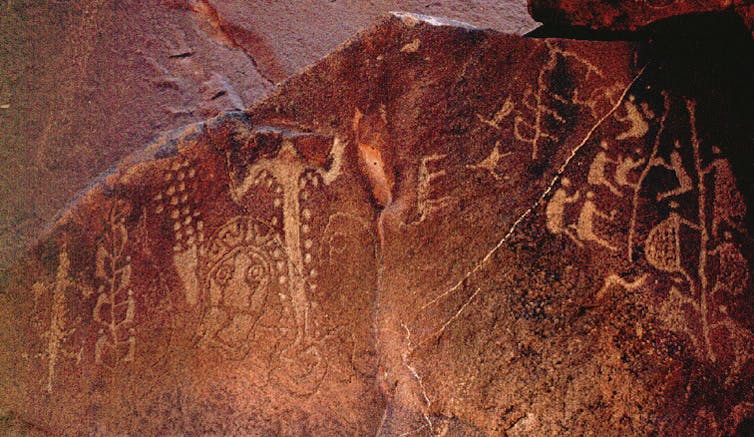

In Australia, continual damage to the rock art on Western Australia’s Burrup Peninsula by the ongoing development of mining infrastructure is a woeful example of heritage seemingly doomed to “death by 1,000 cuts”.

The Burrup engravings are of great cultural significance to local Indigenous people and widely regarded as one of the most important bodies of rock art in the world. As Griffith University’s Paul Taçon has written, 1,700 engraved boulders were relocated and thus decontextualised from their cultural landscape in the 1980s to make way for infrastructure for the North West Shelf gas project.

In 2007, Woodside Petroleum started extending processing facilities for the Pluto Gas Field, having received permission from the WA Government to destroy a significant quantity of the Burrup rock art, against the advice of the government’s own statutory expert panel.

After international protests, the Burrup was then placed on Australia’s National Heritage List. Federal Environment Minister at the time – Malcolm Turnbull – nonetheless prioritised development and gave Woodside permission to destroy 200 rock art panels. The WA Government subsequently gave permission for an additional 170 panels to be relocated (and thus stripped of their cultural context).

In 2008, another company was fined under Federal law for damaging three sites on the Burrup by blasting. As a final gesture of contempt, the WA Government then rescinded the Burrup’s longstanding formal status as a sacred site in 2014. In short, despite global recognition of the value of the Burrup rock art, “everyday development” continues to trump best-practice heritage protection of the site.

Just about every country in the world, including Australia, has legislation of some sort to protect heritage in development contexts. When development is declared imperative, though, as at Ilisu or on the Burrup, or when there are gaping loopholes in heritage legislation, such as with large-scale tree-clearing or housing development in Queensland, the damage continues unrelentingly.

Most of the sites being destroyed in Australia and around the world don’t make the news because they don’t have the monumental scale or romantic cachet of places such as Palmyra, but for the communities who value the heritage in question, the damage is heartbreaking.

While WA is resurrecting its stalled bid to water down its heritage legislation, Queensland is reviewing its Indigenous cultural heritage guidelines, in an effort to tighten things up.

At the other end of the spectrum, the World Bank is completing much the same process after some years of deliberation. The Bank has a formal global standard for cultural heritage broadly based on humanitarian considerations. Still, despite its professed concern, the Bank ranks heritage very low in its order of priorities.

This apparent lack of interest notwithstanding, it is not hard to join the dots empirically between cultural heritage and the other environmental and social standards that the Bank takes more seriously. This is particularly true of Indigenous matters.

The impact of development – and the reputational risk it poses – is understood by most major corporations, even if their execution of heritage protection procedures can be patchy. That’s why Rio Tinto worked with an international group of heritage professionals to develop its global corporate heritage protection guidelines.

Heritage guidelines have also been developed in various parts of the world for use by the military. Peter Stone at the UK’s University of Newcastle has created what he calls “a four-tier approach to the protection of cultural heritage in the event of armed conflict”. It is an invaluable framework and has been formally adopted by the International Committee of the Blue Shield, the “Red Cross for Heritage”.

It is one thing, though, to guide the actions of countries that aim to “play by the rules” in war, whether concerning heritage or people. It is quite another, as Stone recognises, to constrain states which have not signed up to the relevant conventions, including the 1954 Hague Convention and the statutes underpinning the International Criminal Court. The situation is even more problematical with non-state actors such as ISIS, which intentionally flout such conventions in the most dramatic and appalling ways, in relation both to people and heritage.

This is sickeningly obvious in ISIS’s approach at Palmyra. Not only is the organisation facilitating industrial-scale looting there, it has also slaughtered numerous people in the site’s amphitheatre and executed Khaled al-Asaad, the site’s 81-year-old archaeological guardian.

It is highly unlikely that anyone will be brought to justice for these murders, let alone the heritage crimes. The man found guilty for the damage in Mali was surrendered to the court not by Mali, nor the French military (in the country to quell hostilities), but by the neighbouring country of Niger, to where he had fled.

The chances that a similar transfer will occur in relation to Syria or indeed anywhere else are vanishingly small, unless key players see some advantage in making a point of presenting someone to the ICC for propaganda purposes.

Even that would require the ICC to have issued an arrest warrant, which it has not done in connection with Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan or any other recent place where heritage war crimes have likely occurred.

Few clean hands

Why is this the case? It’s simple: no-one has clean hands when it comes to the destruction of cultural heritage in armed conflict. The politics of heritage are Byzantine at the best of times, but adding the possibility of war crimes convictions to the mix makes matters almost impossibly fraught.

So do I think we shouldn’t waste our time and precious resources pursuing heritage war crimes? Not at all. The lasting significance of the Mali decision (and indeed the earlier cases it builds upon) is that it sets a very useful bar.

We shouldn’t, however, now think the ICC is going to deliver us from evil. Its heritage cases will be few and far between and successful prosecutions will probably be even rarer. So while always keeping open the possibilities of action in The Hague, we should focus our minds on these points.

First, as barbaric as heritage war crimes might seem, far more heritage destruction – and thus inexorable damage to human wellbeing – occurs through everyday development. Except in a few cases, that never makes the news.

Second, as “glamorous” as Palmyra or Aleppo might be – as matters of concern – they are not the only places in Syria, much less the Middle East or for that matter the rest of the planet, where armed hostilities are destroying heritage.

Highlighting the situation in Palmyra, or even Syria more generally, might help focus government and public attention on the problem of heritage destruction for a while. Yet we have to be extremely careful that such high-profile examples don’t “suck up all the oxygen” and leave other places to their own devices.

Believe me, there’s a lot of them suffering in every part of the world, whether as a result of conflict, criminal looting or “routine” development: from the unobtrusive small-scale places that make up the bulk of cultural heritage right up to World Heritage sites of the scale and grandeur of Machu Picchu or Angkor. The Trafficking Culture Project and Blue Shield Committee amongst others provide ample evidence of the pressing problem of heritage under threat.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, it is local people with local solutions who are usually best-positioned to make the most of our support – whether in Mali, Syria, Iraq or elsewhere. Joshua Hammer’s new book, The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, for instance, shows how locals put themselves at grave risk to save priceless ancient scrolls from the same Islamist militants who destroyed the World Heritage tombs there.

What is missing in global responses to local heritage destruction is usually not generous offers to rebuild whole sites. Such offers nearly always entail imported expertise and largely exclude local people. Nor generally do we need the heritage-protection airstrikes recommended by the Antiquities Coalition. In the “fog of war”, they are highly likely to damage the very sites they are supposed to protect.

Most often, we need to recognise that relatively small amounts of money judiciously applied through appropriate local players are the way to create sustainable solutions. There are colleagues doing just that right now, through mostly under-the-radar but highly-effective efforts in war-zones such as Syria but also through programs such as the Sustainable Preservation Initiative.

In short, we need a range of responses. Some will involve “big sticks” wielded by institutions such as the ICC but most will work at the grassroots.

On a day to day level, meanwhile, we should all take an interest in what is happening to the heritage around us. If we do, we can help monitor and mitigate the way “everyday” development continually chips away at heritage places large and small, in ways that frequently go unnoticed until it is too late.

Ian Lilley will be online for an Author Q&A between 6:30 and 7:30pm AEST on Friday, 14 October, 2016. Post your questions in the comments below.