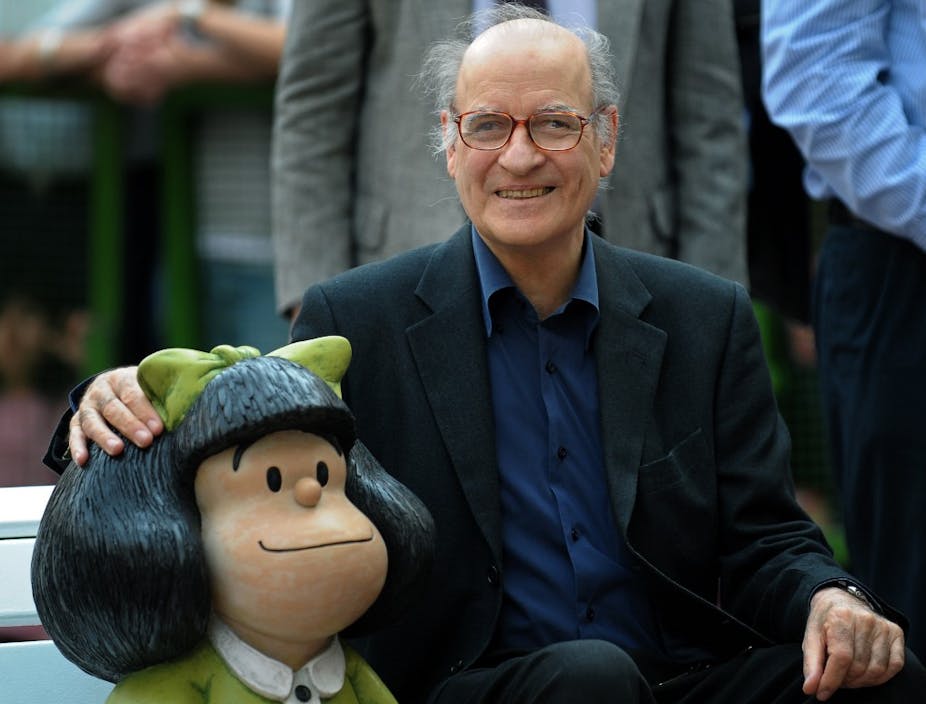

Millions of readers across the world are familiar with the dark-haired, impertinent, soup-hating, diabolically smart and terribly funny little girl named Mafalda. She was imagined by the Argentinian cartoonist Joaquin Salvador Lavado Tejon, known to all as Quino, who passed away September 30 at age 88.

The Mafalda comics ran from 1964 to 1973 and are the most widely known of Quino’s works – they’ve been translated into multiple languages, including braille, and were also turned into an animated series. His legacy also includes numerous other black-and-white comic strips, often wordless and composed of single vignettes.

Through his art, Quino engaged in pointed social critique on a wide range of topics – the state of the world, politics, cliches and prejudices, the middle-class family, social relationships, food and art – where visual and verbal humour played a central role.

Humour as a window into the soul

I personally owe much of the awakening of my political consciousness and rebelliousness to Quino’s black-and-white comic strips. While the meaning of most was obscure to me at first, progressively I found them disturbingly funny over the years, and ultimately this helped trigger my scholarly interest in the use of two powerful tools in the social sciences, drawing and humour, and in affect theories that seek to understand the deep emotional and embodied dimensions of our lives.

The word affect, from the Latin afectus, is often understood in its verb form “to affect” someone or something (actively or instrumentally) or “to be affected” (passively) by someone or something. In an ongoing project, my colleagues and I have stressed how this narrow definition considerably limits our understanding of affect in its noun form (affect, affectivity) and the even richer problematisations of its verb form. Our findings highlight three detrimental consequences.

First, it privileges a limited anthropological assumption of humans reduced to abstract labels (such as “stakeholders” or “employees”), depersonalised ties based on interest, and roles. Second, it hinders our ability to foster deeper relations, where others are ends in themselves instead of means. Third, overall, this leads to weakened ethical engagement in the world we all share.

To counter this, humour proves a powerful tool to bring affectivity back in. It triggers emotional and embodied responses such as laughing, which becomes even more powerful when shared with others.

For instance, research has shown that shared humour fosters socialisation and integration into a group. In my own work, I’ve analysed how shared moments of humour also have the capacity to create empathy and solidarity, allowing a group threatened by violence and injustice to revolt against them.

Quino’s brilliant use of humour can teach us at least three lessons to help us reconnect with our inner affective lives and with others – a deeply needed capacity in an age of social distancing. First, that humour can trigger critical thinking. Second, that humour can foster ethical relationships to others. And third, that humour can powerfully encourage resistance to oppression.

To reuse one of his album’s titles, it is high time for some “Quinotherapy”.

Triggering critical thinking

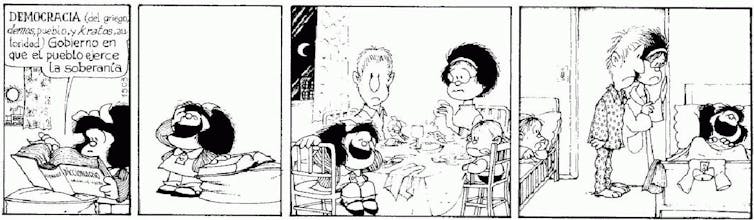

Mafalda’s constant insubordination and (often impertinent) questions leave her friends and particularly her middle-class parents speechless.

In his preface to a 10th-anniversary edition, Umberto Eco noted that Mafalda, as a young girl, has the privilege of childhood innocence, allowing her to question the world. This in turn triggers deeper questions in adults about how they’ve abandoned their ability to be imaginative and reflexive.

Mafalda makes us question what we take for granted, and in a very touching way expresses her dissatisfaction with what she calls the “disastrous” state of the world.

By using satire, Quino often leaves us with open, provocative and often desolating questions, where Mafalda wonders why reasoning and common sense are so hard to find. In so doing, she highlights how being “rational” is not only – as we are made to believe – to be self-interested and calculating. Reason is not opposed to emotion and affectivity, and there are other forms of rationality that foster relationality.

This joins the general aim of critical scholars, who seek to uncover the mechanisms of domination and exploitation that control not only our societies, but more importantly the production of knowledge itself.

It is through such critical thinking that as individuals and as social groups we can imagine alternative ways of living our lives instead of having them being dictated by institutions.

Fostering ethical relationships to others

The ability to question the world and society through critical thinking is often present in Quino’s drawings regarding the ways in which we relate to each other : such relationships are often odd, problematic, messy, unbalanced, but in the end that is what makes them undoubtedly human.

More importantly, Quino often points to the deeply human need to connect with others, of developing empathy and care, or simply of recognising a familiar face in an anonymous world.

Following phenomenologists such as Michel Henry and Emmanuel Levinas, this need for connection – or in philosophical terms, this “embodied affectivity” – is what creates a fruitful and ethical bond between humans. In the words of Paul Ricoeur, it is what makes us “aim for a good life, with and for others, in just institutions”.

Maybe this is why Quino’s life-long editor Daniel Divinski tweeted that his passing would be mourned by all the “good people in the country and in the world”.

Sparking resistance

Comics and cartoons have a long tradition in fostering social critique and stirring up activism, and for me it is one of Quino’s most powerful legacies.

When I left home and moved to a far-away university to study philosophy, among the books that came with me was the Mafalda album A mi no me grite! (“Don’t you scream at me!”), which I discovered as a child on my father’s desk. True to this tradition, in one of his final public appearances, Quino lifted a banner reading “Je suis Charlie” following the 2015 terrorist attack on the offices of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo.

Mafalda and Quino’s other characters question social problems that are still with us today – the feminine condition, nuclear power, political abuse, overpopulation, capitalism, authoritarianism and more. His subtle and poignant humour continues to speak to audiences across the world, and remains a strong call that urges us to resist oppression and to work together to improve our shared condition. Even as Quino rests in peace, he inspires us still.