These days the greatest insult a so-called men’s rights activist can hurl at another man is the word “cuck”, shortened from cuckold, the term for a man whose wife is cheating on him. The word has entered the mainstream, particularly after Donald Trump’s presidential victory saw an alt-right backlash against the achievements of feminism.

But the ideas and language are nothing new; in fact, it was during the Renaissance, from the 16th to the 18th centuries, that Europe had a cultural obsession with cuckoldry.

Back then, it was widely believed that women were more lustful than men, largely because they were subject to the whims of their “wandering womb”. The womb, it was believed, could move independently around a woman’s body, causing her to lose control. Thus, if a man were married, his wife was obviously cheating on him.

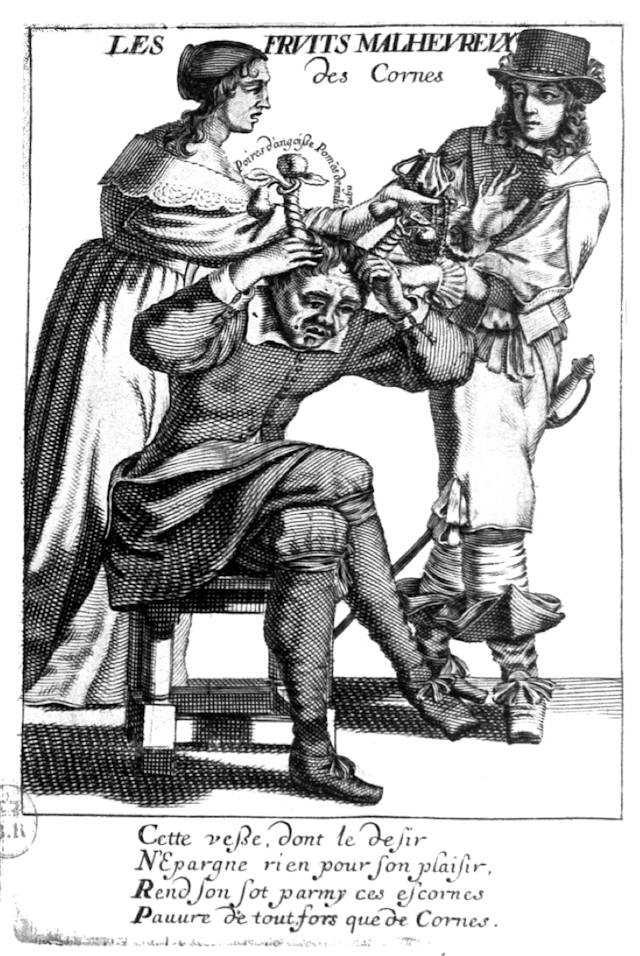

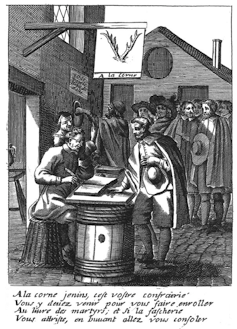

This infidelity would cause the poor husband to grow invisible horns, the ultimate symbol of cuckoldry, and the comic figure of the horned cuckold made its way into fictional songs, engravings, and theatre. It eventually became so ubiquitous as to give the impression of a “brotherhood of cuckoldry” wherein all wives were adulterous, and all husbands their hapless fools.

In Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, a play all about love, marriage, and deception, Benedick jokes about never getting married because it means instant cuckolding:

The savage bull may; but if ever the sensible Benedick bear it, pluck off the bull’s horns and set them in my forehead, and let me be vilely painted, and in such great letters as they write ‘Here is good horse to hire,’ let them signify under my sign ‘Here you may see Benedick the married man’.

What’s with the horns?

The animal symbolism connected with cuckoldry is complex. The basis of the word “cuckold” is found in the cuckoo, a bird which lays its eggs in other birds’ nests, forcing the unsuspecting bird to raise offspring which are not its own. The anxieties around paternal lineage due to a cheating wife are obvious in this naming.

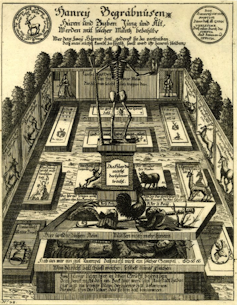

Cuckoos, of course, don’t have horns. Countless explanations have been offered for the link between horns and cuckoldry, such as in the 18th-century German print “Hanrey Begrabnusen” (“Cuckolds’ Graveyard”), which suggests a whole panoply of horned animals as the bestial source.

The ox - a castrated bull - alludes to the impotence of the wronged husband; while the stag suggests that the cuckolded husband has relinquished his status as a virile sexual pursuer and has become instead his wife’s “prey”.

The theory that intrigues me, however, is the one of the capon (castrated cockerel). This refers to the formerly prevalent practice of cutting off the spurs from the legs of a castrated cock and engrafting them on the root of the excised comb, where they could grow and become horns, sometimes several inches long.

Capons, lacking in sexual hormones, grow fat due to their lack of activity and were prized (and still are) for their moist, tender meat. Their lack of aggression also meant that they could be kept with other hens and roosters. The practice of grafting a spur on their heads served to distinguish them from the other, fully-sexed birds.

This theory certainly fits with the traditional depiction of cuckolded husbands in the early modern period as older, impotent and often overweight men whose wives seek out younger, more virile and more attractive partners, as in many plays by the French writer Molière.

Playing the fool

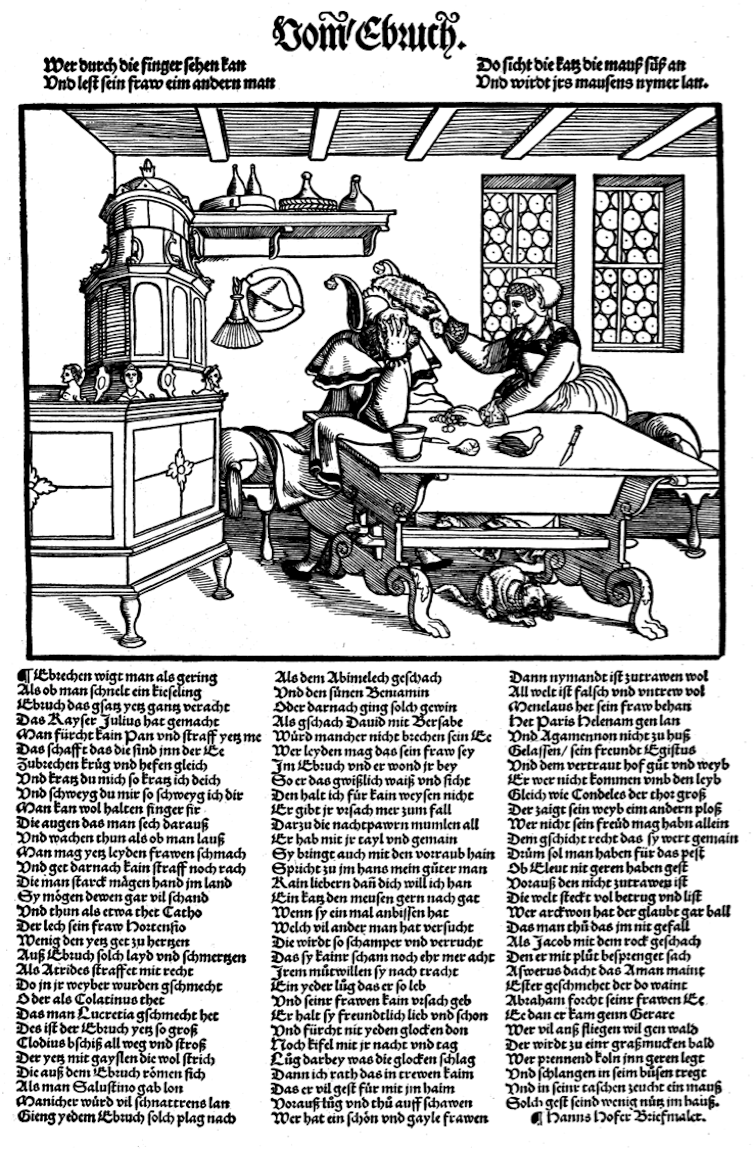

The mockery of cuckolds also links these men to the character of the fool. In the following 16th-century German woodcut, called On Adultery, a woman places a fools’ cap (or Narrenkappe - literally, fool’s hood, giving rise to the term “hoodwink”) on her husband’s ears and rubs his head with a foxtail, another symbol of foolishness.

As well as plays and prints, ballads also mocked the cuckold as a hen-pecked husband who was overly submissive to his wife. This 17th-century ballad summoned all cuckolds to meet at Cuckolds-Point, an area on the Thames in East London, to repair the footpath that their wives would take with their lovers to Horn-Fair, a carnival-like parade that took place every October:

Here is a Summons for all honest Men,

belonging to the Hen-peck’d Frigate;

And I will tell you the place where and when,

both Gravel and Sand for to dig it;

To mend the ways, ‘tis no idle Tale,

remember your Foreheads adorning,

At Cuckolds-Point you must meet without fail,

by seven a Clock in the morning.

Although this song seeks solidarity in the brotherhood of cuckoldry, others are less kind. The following French song gossips about a cuckold’s torture at the infidelity and sexual voracity of his wife. They can no longer go to a public place because of his inability to control her, and the shame is so great he eventually commits suicide whereupon she follows him to Hell:

There is a man in our town

who is jealous of his wife.

He is not jealous without cause,

but he is cuckolded by everybody.

The 16th-century musician Thomas Whythorne claimed that public knowledge of one’s cuckolded status doomed a man to social failure:

for he that is known to be a notorious cuckold cannot be taken upon quests, and is barred of diverse functions and callings of estimation in the commonwealth as a man defamed, so that you may see what a goodly thing it is when a man’s honesty and credit doth depend and lie in his wife’s tail.

That reference to “his wife’s tail” as the (animalistic) thing that decides a man’s worth in his community makes it clear for how long men have valued women only in sexual terms.

And it also shows that men have been ridiculing each other in terms of sexual inadequacy for a very long time.