The launch of a new internet service provider (ISP) in New Zealand isn’t something that would normally be worth mentioning.

But the launch of FYX (pronounced “fix”) by established online services provider Maxnet has already made a splash in New Zealand because FYX offers “global mode” internet access.

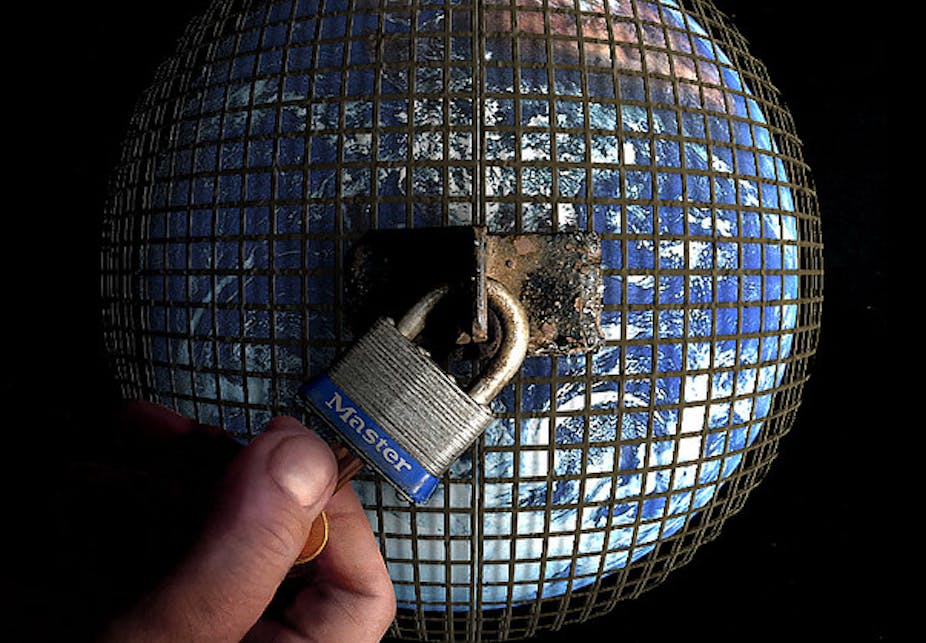

This is designed to avoid “geoblocking” – the restriction of content to the country or region of origin – as implemented in services such as ABC iView, BBC iPlayer, Netflix, Apple’s United States iTunes store and many others.

While “global mode” is an exciting development for consumers, the legality of such circumvention services is unclear. The likelihood of similar services appearing in Australia will depend on the success of FYX in New Zealand and the compatibility of such services with Australian law.

International copyright law is founded on what critics, such as communications researcher Herbert Schiller, damn as “information colonialism”. Markets such as Australia and New Zealand, pay higher prices than the US domestic market for videos, software, music, books and other content.

Consumers in these markets are often subjected to long delays before the content is available locally. This is reinforced by technological mechanisms that inhibit the free flow of copyright material across national borders.

Most people are familiar with technological protection measures (TPM) in the form of region coding on DVDs. Those TPMs try to prevent the disc being copied and try to prevent playback in a place other than the market in which the disc was sold.

Region coding allows Hollywood to segment global markets, releasing movies to one market at a time, maximising the effect of promotional campaigns, for instance.

A second purpose of region coding is to prevent the movement of DVDs between countries with differently priced DVDs. The TPMs claw back Australian law’s support for consumers through parallel import measures. That is, it’s legal to buy DVDs, books and other material direct from another region for personal rather than commercial use.

Geoblocking is this offline market segmentation continued into the online world.

FYX is being promoted as a solution for New Zealand consumers wishing to access geoblocked content ahead of local release dates.

Promotion of the ISP in that way is interesting because it poses questions about the nature of online copyright law - something that is global rather than parochial - and follows recent decisions by Australian courts about the liability of ISPs for copyright infringement by their end-users.

In the case of Roadshow vs iiNet in April, the High Court found iiNet had not authorised its customers to breach copyright (by downloading films, TV programs and music through BitTorrent).

Australian law provides broad immunity - the “safe harbour” - for internet providers whose customers have infringed copyright. This immunity does not apply where the provider has authorised the infringement.

Because the main - but, importantly, not sole - feature of FYX is the circumvention of geoblocking, FYX will face questions about whether it would fail Australian legal tests of authorisation.

In NRL vs Optus – likely to be appealed to the High Court – the Federal Court decided Optus was at least partially responsible for infringing the copyright of broadcasts which it was recording for consumers.

In Australia, FYX or a similar service might also be considered responsible for enabling breaches of copyright.

But according to NZ intellectual property law commentator Justin Graham, FYX is in the clear under NZ law:

“It [the bypassing of geographical restrictions] is consistent with New Zealand’s policy on intellectual property, parallel importing and geographical restrictions”.

Australian law and New Zealand law both allow the bypassing of region coding on DVDs. But the application of these laws to geoblocking is yet to be tested.

Is FYX in breach of New Zealand or Australian law? The test for any legal question is ultimately in what the relevant court says.

FYX appears to be offering a service that enables what many consumers would consider to be a victimless act, but there is damage to local rights holders who may have paid a high price for the rights to broadcast that content.

Prior to FYX, a local rights holder could only try to enforce their rights against individuals who were downloading the copyright content. In providing a commercial service and profiting from the actions of its customers, FYX is now a convenient target for local rights holders.

FYX will, if challenged, presumably argue it is not breaking any law. Its customers may be infringing the rights of movie studios, broadcasters and other rights owners but FYX is not responsible for what those consumers do. That argument would be consistent with iiNet’s persuasive claims in the High Court.

But because it is promoted specifically as a service which circumvents geoblocks FYX will have a hard time distancing itself from the activities of the consumer and claiming to be a mere provider of technology and internet access.

Due to the commercial nature of FYX, we will likely see copyright holders claim compensation from FYX; after all, the content is what will attract their subscribers.

One thing is certain: whenever copyright holders are threatened by an advance in technology there is rhetoric about disaster, crime and the need for government action.

Some 30 years ago the then Motion Picture Association of America president, Jack Valenti, described the VCR as the movie industry equivalent of the Boston Strangler.

Reports of the death of movies – or of broadcast television and the movie studios – seem to have been premature.

We should think carefully about the inevitable alarmist claims regarding FYX and be wary about movie industry calls for new laws that protect their interests at the expense of Australian consumers.