By their very nature, Fathers of the House of Commons tend to span ages. That a neophyte associated with the “white heat” of Harold Wilson’s New Britain should have occupied the role in his ninth decade is to remind us that half a century is a long time in politics.

Gerald Kaufman, who has died aged 86 – a month to the day after another Father, Tam Dalyell – had been one of the dynamic men, and one woman, behind Ned Sherrin’s epochal BBC television series That Was the Week that Was. He was then one of the dynamic men, and one woman, behind Harold Wilson’s Labour ephocal government, first elected, narrowly, in October 1964.

That Wilson benefitted from the irreverence TW3 brought to British public life did nothing to help him dodge the ordure flung from all quarters when his economic policy spectacularly disintegrated in November 1967. By then, Kaufman – who had been a journalist at the Daily Mirror for a decade – occupied the critical role of the prime minister’s parliamentary press liaison officer, metaphorical bucket and shovel never far from hand.

More than that, Kaufman was a fully functioning fixture in Wilson’s kitchen cabinet. The myriad diaries and memoirs of power in those years attest to that singular assemblage of gossips and intriguers (not least the Prime Minister himself) at the heart of the state in the transformative years between 1964 and 1970.

Like many courtiers before and since, Kaufman sought the legitimacy of election, and a place for himself in the House of Commons. He was duly returned, in June 1970, as MP for Manchester Ardwick, a constituency redrawn for the 1983 general election as Manchester Gorton. It was always a safe seat. So safe, indeed, that it won’t be a newsworthy by-election even for Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party.

The hope proffered by Wilson’s much greater victory in March 1966 was soon lost, just as, unexpectedly nevertheless, was the general election of 1970. When Labour returned to office, narrowly, in February 1974, Wilson appointed Kaufman a junior minister. This would be a position he would occupy throughout the fragile 1974-9 Labour governments. Typically, Kaufman turned his experience into a waspish, widely-read, “manual”: How to be a Minister. It was one of very few self-penned politicians’ texts to acquire a positive reputation of its own. He wasn’t to know that he wouldn’t be able to add to it through personal experience. In 1979, aged 48, he lost ministerial office, never to regain it.

A guide for would-be ministers

On the Labour right, and one of only two MPs to tell Michael Foot that he should stand down as leader, Kaufman found the party to move in his direction during the “wilderness years”. He was virtually resident on news and current affairs television throughout the 1980s and 1990s, shadowing, and fluently fulminating against, successive environment, home, and foreign secretaries. The unfashionably electable Labour Party of Tony Blair came too late for Kaufman, although the imminence of office occasioned a second edition of How to be a Minister, required reading for the by-then vast majority of Labour MPs who had no idea.

Wilson had been a master of what would later be called soundbites, many of them crafted by Kaufman, so it’s apt that the wordsmith has one of his own; one of the hardest-working in British politics. Kaufman described Labour’s 1983 manifesto – committing the next Labour government to such outlandish policies as withdrawal from Europe – as the “longest suicide note in history”. Had a royalty been paid every time it has been used, such as in a life of Margaret Thatcher or Neil Kinnock, or a history of the Labour party or of Britain in the 1980s, it would have minted its coiner, and, through this week’s obituaries, his beneficiaries.

Kaufman was Jewish and encountered anti-Semitism throughout his life, but no stronger or more consistent critic of Israel could be found anywhere in Parliament; it was one position, at least, to bind him with the current leadership.

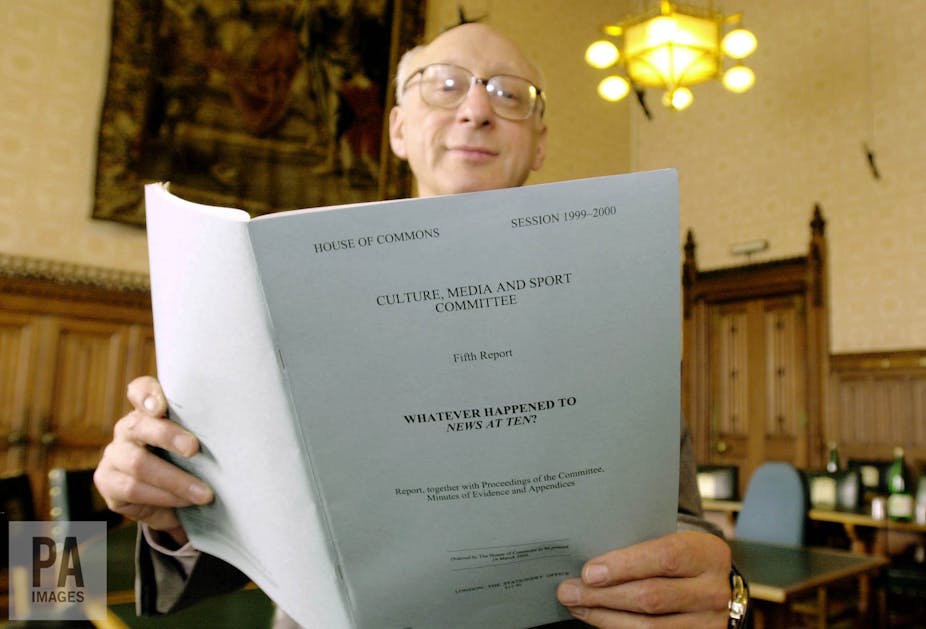

It was perhaps towards the end of his career, engaging with the cultural sector, that Kaufman had the greatest impact, in a role he may have found the most fulfilling. For 13 years, as the first chairman of the Select Committee on National Heritage (the department less fustily rebranded Culture, Media and Sport in 1997), he sat centre stage interviewing his guests on what was dubbed the Gerald Kaufman Show.

Deliberative of deportment and precise of pronouncement, Kaufman was increasingly inclined to the donning of dazzling apparel, betraying a lifelong love of Hollywood musicals. Sir Gerald, as he became, Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Dance group, stitched satire, suicide notes and sequins with serious panache.