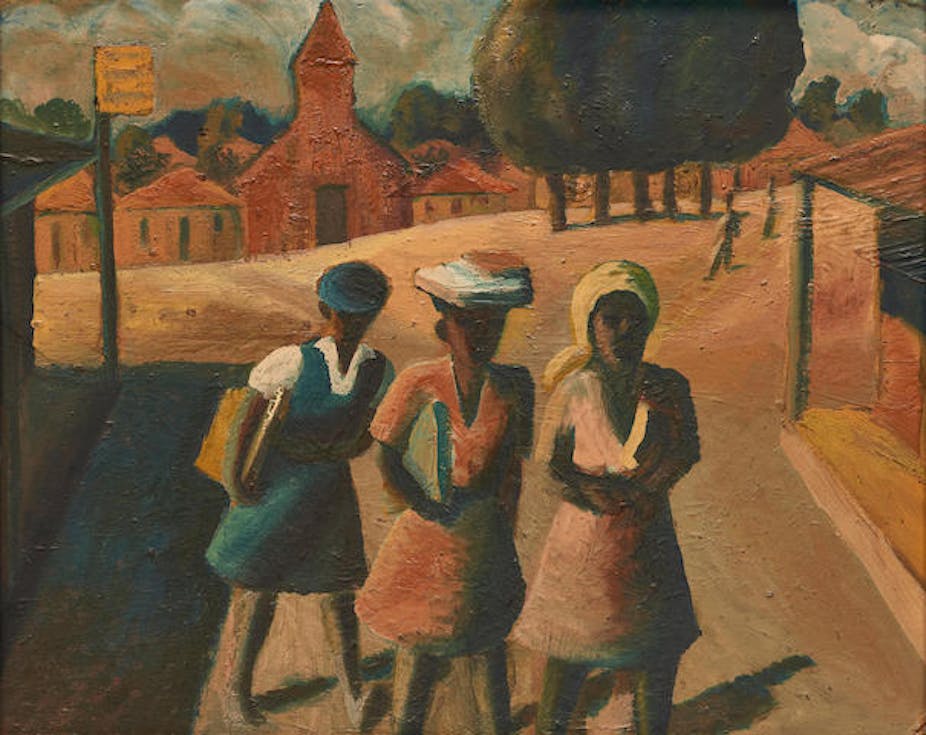

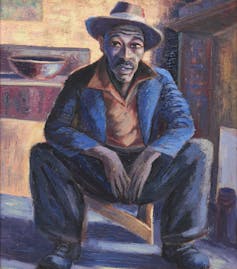

When two recently discovered paintings by revered South African artist Gerard Sekoto (1913-1993) – Portrait of a Man (Lentswana) and Three School Girls – went on auction at Bonhams London early in September 2018, there was some anticipation about what kind of prices they would fetch. When the hammer fell they garnered just over £380,000 and £300,000 respectively.

In pound sterling terms it was way off the record set for Sekoto’s Yellow Doors, District Six, which sold at the same auction house for just over £600,000 in March 2011. But in South African rand terms – and using exchange rates at the time of the purchases – the sales look rosier at R7,45-million and R6 million, compared to 2011’s R6,8-million for Yellow Doors.

While the fluctuating and often volatile exchange rate creates a certain amount of confusion about how to read and understand Sekoto’s work relative to the different markets in which it sells, his work consistently (and significantly so, given his pedigree in South African art history) under-performs in relation to the likes of compatriot Irma Stern (1894-1966).

At the same Bonham’s sale in March 2011 that saw Yellow Doors, District Six sell for a record sterling price, so too did Stern’s Arab Priest sell for a touch over £3-million (R34,3-million at the time). Stern holds eight of the 10 auction records for South African art.

One does not want to undermine the extent to which Stern bucks the international precedent in which auction records are dominated by male artists. But in many ways her prominence in the South African art market represents the resilience of apartheid era tastes and preferences, which at the time largely overlooked the quality of concurrent black artists. And through the public performance of the auction, this same preference is visibly borne out every time the hammer falls.

Contemporary offers

So, what is it that’s keeping the likes of Sekoto’s work off the boil? There are at least six factors to consider.

First is the greater (and increasing) preference for the contemporary over the historical. In 2017 the Barloworld corporation sold off most of its historical collection at auction to fund a new focus on contemporary art, particularly photography.

Most of the offloaded works were by white artists. Nonetheless the auction reflects a view that the historical is compromised and too difficult to associate with. For many corporates the contemporary offers a slate that is more alive, easier to inhabit, and hipper. Sadly, in this view (dare I say prejudice), black artists like Sekoto get whitewashed and swept out the door along with all the other historical artists.

Second is the alienating environment of the art world itself. While events such as the Joburg Art Fair has gone out if its way to present a programme that isn’t as narrowly white as in the past, there are few opportunities to purchase historical artworks. And if it’s not a privately brokered deal, the best opportunity to purchase a Sekoto is at auction.

All the South African auction houses that attract quality works by Sekoto are white owned, run and patronised. If you’re not white it’s hardly a welcoming environment in which to enjoy spending millions on art.

Third is how art auctions frame their sales, particularly those that take place in London. Bonhams started its South Africa sales in 2006. Country-specific auctions are not uncommon, but for a country like South Africa, whose art history is a relative mystery compared to North America and Europe, it can leave it a little isolated.

When isolated like this it’s more difficult for collectors wanting to build a meaningful collection to find affinities and connections with artists from elsewhere in the world. It remains to be seen whether Sotheby’s London, in choosing to start a modern and contemporary African art sale in 2017, will find better traction for the likes of Sekoto in a wider African context.

Fourth is the lack of wider and sustained government support for artists whose works should more meaningfully constitute national heritage.

The South African Heritage Resource Agency does flex its muscles by refusing export permits for artworks that are deemed to have cultural and heritage significance. But this is a double-edged sword. While artworks remain in South Africa it also restricts buyers to a local pool.

The Department of Arts and Culture, under then minister Brigitte Mabandla, was instrumental in brokering the return of Sekoto’s estate from France where he died in exile in 1993. It also managed to have the crippling French death taxes waived.

But the South African government has since reneged on most opportunities to cement Sekoto’s legacy.

Fifth is the lack of sustained momentum around research on Sekoto’s oeuvre. First introduced to Sekoto by academic Chabani Manganyi, historian Barbara Lindop’s “Gerard Sekoto” (1988) remains the definitive catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work. Along with the publication of Manganyi’s “A Black Man Called Sekoto” in 1996, it seemed we were set for a bibliography of scholarly work on Sekoto. But this was not to be.

The absence on new works on Sekoto stands in stark contrast to the richness of scholarly works on Irma Stern, and importantly, by a wide range of scholars.

And finally, there’s the role of families and foundations in continuing artistic legacies. The Gerard Sekoto Foundation was set up at the insistence of the French government as a precondition for them wavering the death taxes. It is an organisation that survives largely on the passion and generosity of its founder member, Lindop.

Without any evident support from Sekoto’s family, Lindop is a lone crusader against the Sekoto fakes, copies and stolen works that so often undermine an artist’s prices. It’s unrelenting work, and without the prospect of handing over her vast visual knowledge to a new generation of champion.

The Sekoto Foundation is currently under the umbrella of the Norval Foundation. But its own museum seems more invested in the alumnus of white art history such as Edoardo Villa and Cecil Skotnes. Whether this relationship is sustainable in the long term remains to be seen.